Separation Anxiety Disorder

advertisement

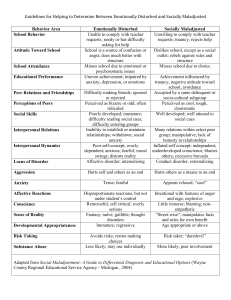

Separation Anxiety Disorder Psychology 7936 Child Psychopathology 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Overview of DSM-5 Separation Anxiety Disorder Neurobiological substrates Environmental influences New model of Separation Anxiety Disorder Treatment DSM-V and Separation Anxiety Disorder (SAD) • Developmentally inappropriate and excessive fear or anxiety concerning separation from those to whom the individual is attached, as evidenced by at least three of the following: 1. Excessive distress in anticipation or when experiencing separation 2. Persistent/Excessive worry about the loss of a major attachment figure (MAF) or harm to said figure 3. Excessive worry about experiencing an untoward event such as kidnapping 4. Persistent refusal to go out, away from home (e.g., to school) because of fear of separation 5. Excessive fear about being alone without MAF (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) DSM-V and Separation Anxiety Disorder 6. Refusal to sleep away from home or to go to sleep without being near MAF 7. Repeated nightmares involving separation from MAF 8. Repeated complaints of physical symptoms such as headaches or stomachaches when separation occurs or is anticipated (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) DSM-5 model of Separation Anxiety Disorder DSM-5 Schematic of Separation Anxiety Disorder Environment • Life stress or loss (e.g., a death in the family) • Parental overprotection/intrusiveness • Entering a relationship • Becoming a parent Genetic/Physiological Genetic predisposition Enhanced sensitivity to CO2 Core features: • Distress in anticipation or when experiencing separation • Persistent/Excessive worry about the loss of MAF • Excessive worry about an untoward event such as kidnapping • Persistent refusal to go out, away from home • Excessive fear about being alone without MAF • Refusal to sleep away from home or to go to sleep without being near MAF • Repeated nightmares involving repeated separation from MAF • Psychosomatic complaints when separation occurs or is anticipated Onset of Separation Anxiety Disorder • Anxiety exceeds what is expected given the person’s developmental level: • Infants from 6 to 30 months usually exhibit separation anxiety with intensity increasing between 13 and 18 months. • Separation anxiety usually declines between 3 and 5 years of age when the child is able to understand that separation is temporary. (Bernstein & Victor, 2009) Onset of Separation Anxiety Disorder cont’d • SAD is thought to have two separate onsets (Kearney, Sims, Pursell, & Tillotson, 2010): • Juvenile period onset (JSAD) • Adulthood period onset (ASAD) • In children, SAD typically begins between 7-9 years old (Last, Perrin, Hersen, & Kazdin, 1992). • Some children develop SAD as a result of stressful life event • Some children exhibit symptoms without a clear precipitating event (Bernstein & Victor, 2009) Prevalence of Separation Anxiety Disorder • Rates of SAD are reported at 3-6.8% (Bernstein & Victor, 2009). • SAD is more prevalent in children compared to adolescents. • Some studies show a higher rate of SAD in girls whereas others show equal rates (Bernstein & Victor, 2009). • One study found 50% of youth sampled exhibited subclinical levels of SAD but do not meet full criteria (Kashani & Orvaschel, 1990). Prevalence of Separation Anxiety (Kashani & Orvaschel, 1990) Prevalence of Separation Anxiety (Kashani & Orvaschel, 1990) Anxiety Disorder Prevalence in Children (N =70) 60.0% 50.0% 40.0% 30.0% 20.0% 10.0% 0.0% 8 years SAD Fear of strangers 12 years Past imperfections 17 years Social situations Impairment and diagnosis of SAD • Data suggest that until 6 or more symptoms are present, impairment remains relatively low. • Impairment was measured using Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment and parent reports. (Foley et al., 2008) Course • Longitudinal studies show (Kearney et al., 2010): • First assessment (M = 3.5 years old): • 26.7% met criteria (i.e., 3+ SAD symptoms) • 43.3% were subclinical (i.e., 1 or 2 symptoms) • 30% had non-clinical status • Second assessment 3.5 years later (M = 7 years old): • 6.8% of children met SAD criteria • 25% were subclinical • 68.2% had non-clinical status • SAD was assessed using Anxiety Disorder Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Child and Parent Versions (ICC = .85; Silverman, Saavedra, & Pina, 2001). Prognosis in childhood • One study examined the course of childhood psychiatric disorders and found (Cantwell & Baker, 1989): • A total of 151 cases were included of which 9 children met SAD criteria. • The children aged from 2.4 – 6.6 years old. • Of those 9 children: • • • • 4 were absent of psychopathology 5 years later 1 still had SAD 2 had behavioral disorders 3 had anxiety disorders • Another study found that at 18 month follow-up 20% of children still met criteria for SAD (Foley et al., 2008). • There does appear to be some lasting effect of the disorder in a substantial amount of adults who had SAD as children. Prognosis into adulthood • There is evidence that SAD leads to panic disorder and anxiety disorder proneness in adults (Manicavasagar, Silove, Curtis, & Wagner, 2000). • 50-75% of children with panic disorder currently or previously met criteria for SAD (Bernstein & Victor, 2009). • 75% of adults with anxiety as a presenting problem report having SAD symptoms as a child (Milrod et. al., 2014). • There is equivocal evidence that Adult Separation Anxiety Disorder is related to anxious attachment (Manicavasagar et al., 2009). Prognosis Adolescent and adulthood • A meta-analysis looked at odds ratios for risk of adult psychopathology and found: • Panic disorder with and without agoraphobia did not yield significantly different odds ratios (i.e., OR = 3.59, OR = 4.19, respectively). • Panic disorder: Odds Ratio = 3.45, N = 25 studies • Any anxiety disorder: Odds ratio = 2.19, N = 5 studies* • Major depressive disorder: Non-significant after adjusting for publication bias* • Substance use: Non-significant odds ratio * results take publication bias into account (Kossowsky et al., 2013) Comorbidity of Separation Anxiety Disorder • • • • Generalized anxiety disorder: Specific Phobia: ADHD: Social phobia: 33-74% 13-58% 17-22% 8-20% • Enuresis: • Sleep terror disorder: • Dysthymic disorder: 8% 8% 2-13% • Major depressive disorder: • Panic disorder: 0-8% 2-4% (Bernstein & Victor, 2009; Last, Perrin, Hersen, & Kazdin, 1992; Verduin & Kendall, 2003) 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Overview of DSM-5 Separation Anxiety Disorder Neurobiological substrates Environmental influences New model of Separation Anxiety Disorder Treatment Hypercapnia • Data originally showed that individuals with Panic Disorder (PD) had an enhanced sensitivity to air that contains 35% CO2. • Inhaling the concentration of CO2 induces panic attacks in 50-70% of individuals with PD • Children with SAD were found to also react to a 35% CO2 mixture. • Monozygotic twins have a significantly higher concordance rate compared to dizygotic twins for the hypercapnia phenotype (i.e., 55.6% and 12.5%, respectfully; Bellodi et al., 1998). • Extensive genetic research found that a gene that influences hypercapnia also influences panic attacks (Battaglia et al., 2009) • The SAD to Panic Disorder conversion hypothesis suggested a connection between the two disorders. Genetic structural equation model • A: Additive genetic effects • CPL: Childhood parental loss • E: Unique environmental influence • L: Common latent variable determined by latent genetic and environmental factors related to all phenotypes (Battaglia et al., 2009) Suffocation False Alarm (SFA) Theory • The theory proposes that panic is caused by an alarm system that begins physiological false alarms. • In the lab, if lactate is infused intravenously and CO2 is inhaled, most panic prone individuals will have a panic attack. • The hypothesized cause for CO2 and Lactate initiated panic is that, generally, an increase in CO2 and lactate in the brain indicates suffocation. • This theory is supported by: • High prevalence rates of panic in those with lung disease, asthma, COPD and those who were tortured with suffocation compared to other methods. • There is a much higher prevalence of PD in those with asthma (6-24% compared to 13%) • Cigarette smoking is a risk factor for panic attacks, quitting smoking reduces the chance of a panic attack. (Preter & Klein, 2008) SFA and Separation Anxiety Disorder • As mentioned previously, SAD in childhood is significantly related to Panic Disorder • 50-75% of children with PD met SAD criteria, Odds ratio of SAD to PD: 3.45 and 75% of adults with anxiety as a presenting problem report having SAD symptoms as a child . • Separation anxiety and PD are therefore theorized to be similarly controlled by opioidergic processes (Preter & Klein, 2008). • Separation distress in primates is moderated by opioid agonists (Kalin, Shelton, & Barksdale, 1988). SFA and Separation Anxiety Disorder • Kalin et al. (1988) administered 0.1 mg/kg of morphine to infant primates and found significantly less distress vocalizations, whereas Naloxone (0.1 mg/kg) & Morphine together partially blocked the effect. (Preter & Klein, 2008) http://bp3.blogger.com/_9M9yKRI9XVw/R07MCQ9iPZI/AAAAAAAAAKc/tP8yH_S2oWQ/s1600-h/bupfig01en.jpg SFA and Separation Anxiety Disorder (Kalin et al., 1988) SFA and Separation Anxiety Disorder • Clonidine, however, does not reduce the effect of “separation-induced” vocalizations in infant primates (Kalin & Shelton, 1988). • 67 µg/kg was used originally and showed reduced activity levels, but not reduced vocalizations • Dosage was then increased to 100 µg/kg and behavioral sedation was observed in addition to reduced vocalizations • This study suggests that sedative effects are not the cause of reduced separation vocalizations • Additionally, a placebo-controlled trial shows that codeine allows higher levels of CO2 in the blood to be tolerated while breath holding (Stark et al., 1983). • These data support the theorized SFA mechanism that SAD and PD are similarly due to an episodic functional endogenous opioid deficit. (Preter & Klein, 2008) 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Overview of DSM-5 Separation Anxiety Disorder Neurobiological substrates Environmental influences New model of Separation Anxiety Disorder Treatment Attachment and Separation Anxiety Disorder • DSM-V cites attachment issues as a risk factor. • Recent meta-analytic evidence shows: • Insecure attachment does not appear to be significantly related to separation anxiety • The relationship was non-significant, small (r = .28, 95% CI [.06, .62]) and the confidence interval contained 0. • Two samples were used for a total N of 59, so these results may be an artifact of sample size (Colonnesi et al., 2011) Effects of Maternal Separation Anxiety • Maternal separation anxiety: “an unpleasant emotional state that reflects a mother’s concerns and apprehensions about leaving her child.” Anxiety may be reflected in feelings of worry, sadness, or guilt that accompany short-term separations Effects of Maternal Separation Anxiety • One study examined the effect of Maternal separation anxiety on children (Biadsy-Ashkar & Peleg, 2013). • Differentiation of self: the degree to which one is differentiated from another. A healthy/differentiated person does not experience the loss or separation from another as a loss of the self (Biadsy-Ashkar & Peleg, 2013). • Differentiation was measured with the Differentiation of Self Inventory (DSI; (Skowron & Friedlander, 2009). • DSI is comprised of four subscales: • • • • Emotional reactivity I-position Emotional cutoff Fusion with others Effects of Maternal Separation Anxiety • Separation anxiety in children was measured during a video taped strange situation type procedure. • Two raters independently rated displayed separation anxiety in children. • Studies were conducted in kindergarten classrooms between 7:30 am and 9:00 am. • Data were collected over three days. • Multiple regression analyses were completed • N = 38 (Peleg, Halaby, Einaya, Whaby, 2006) • EC: Emotional cutoff, the extent to which the mother ineffectively handles emotionally charged situations is negatively related to secure separation. • PSEC: The more the mother worries about separation with the child the more the child experiences separation anxiety, possibly interacting with the relationship of EC 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Overview of DSM-5 Separation Anxiety Disorder Neurobiological substrates Environmental influences New model of Separation Anxiety Disorder Treatment DSM-5 model of Separation Anxiety Disorder DSM-5 Schematic of Separation Anxiety Disorder Environment • Life stress or loss (e.g., a death in the family) • Parental overprotection/intrusiveness • Entering a relationship • Becoming a parent Genetic/Physiological Genetic predisposition Enhanced sensitivity to CO2 Core features: • Distress in anticipation or when experiencing separation • Persistent/Excessive worry about the loss of MAF • Excessive worry about an untoward event such as kidnapping • Persistent refusal to go out, away from home • Excessive fear about being alone without MAF • Refusal to sleep away from home or to go to sleep without being near MAF • Repeated nightmares involving repeated separation from MAF • Psychosomatic complaints when separation occurs or is anticipated New model of Separation Anxiety Disorder Environment • • • • Life stress or loss Maternal characteristics Attachment Non-specified environmental effects • Positive/negative reinforcement exchanges OR1: 2.19 Core features 8 DSM Criteria Any anxiety disorder OR1: 3.45 Panic disorder Anxiety prone genotype Secondary features Episodic deficit in endogenous opioids Enhanced sensitivity to CO2 and lactate Suffocation false alarm 1 OR indicates Odds Ratio • • • • • • Clinging/shadowing behavior School refusal Can’t have sleepovers Sadness, Inattention Demanding attention 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Overview of DSM-5 Conduct Disorder Neurobiological substrates Environmental influences New model of Conduct Disorder Treatment APA Division 53 • There is no section for Separation Anxiety Disorder. • As a substitution, the Anxiety General Symptoms section can be used. • There are no Well-established psychosocial treatments for Anxiety. • Probably efficacious treatments: • • • • • Individual CBT for Anxiety Group CBT for Anxiety (without parents) Group CBT Anxiety with parents Social skills training Exposure treatment APA Division 53 • Possibly efficacious treatments: • Individual CBT for Anxiety with parents • Group CBT for Anxiety with parental anxiety management for anxious parents • Family CBT for Anxiety • Parent CBT for Anxiety • Group CBT for Anxiety with parents plus internet therapy Potentially Harmful Treatments (PHT; Lilienfeld, 2007) • Probably harmful: probably produce harm in some clients a) Randomized controlled trials replicated by at least one other team b) Meta-analyses of RCTs for the treatment or c) Consistent and sudden incidence of low-base-rate adverse events following therapy • Possibly harmful: preliminary evidence showing harmful effects a) Quasi-experimental design that have been replicated by at least one independent team or b) Replicated single case designs Potentially Harmful Treatments (Lilienfeld, 2007) • Possibly harmful: Relaxation treatment for Panic-Prone Patients • These data suggest that caution should be taken with children who have SAD because of the shared etiology with PD. • Small-sample controlled case studies suggest that some patients with PD experience paradoxical increases in anxiety and panic attacks during relaxation. • The studies did not include habituation in treatment by graded exposure. • More research is needed. References 1. American Psychiatric Association. (2013). DSM 5. American Journal of Psychiatry (p. 991). doi:10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.744053 2. Atlı, O., Bayın, M., & Alkın, T. (2012). Hypersensitivity to 35% carbon dioxide in patients with adult separation anxiety disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 141(2-3), 315–23. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2012.03.032 3. Battaglia, M., Pesenti-Gritti, P., Medland, S. E., Ogliari, A., Tambs, K., & Spatola, C. A. M. (2009a). A genetically informed study of the association between childhood separation anxiety, sensitivity to CO(2), panic disorder, and the effect of childhood parental loss. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66(1), 64–71. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.513 4. Battaglia, M., Pesenti-Gritti, P., Medland, S. E., Ogliari, A., Tambs, K., & Spatola, C. A. M. (2009b). A genetically informed study of the association between childhood separation anxiety, sensitivity to CO(2), panic disorder, and the effect of childhood parental loss. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66(1), 64–71. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.513 5. Bellodi, L., Perna, G., Caldirola, D., Arancio, C., Bertani, A., & Di Bella, D. (1998). CO2-induced panic attacks: a twin study. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 155(9), 1184–8. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9734540 6. Bernstein, G., & Victor, A. M. (2009). Separation Anxiety Disorder and School Refusal. In M. K. Dulcan (Ed.), Dulcan’s Textbook of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (1st ed., pp. 325–338). American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. Retrieved from http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/dulcanstextbook-of-child-and-adolescent-psychiatry-mina-k-dulcan/1100901813?ean=9781585623235 7. Blackford, J. U., & Pine, D. S. (2012). Neural substrates of childhood anxiety disorders: a review of neuroimaging findings. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 21(3), 501–25. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2012.05.002 8. Cantwell, D. P., & Baker, L. (1989). Stability and natural history of DSM-III childhood diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 28(5), 691–700. doi:10.1097/00004583-198909000-00009 9. Colonnesi, C., Draijer, E. M., Jan J M Stams, G., Van der Bruggen, C. O., Bögels, S. M., & Noom, M. J. (2011). The relation between insecure attachment and child anxiety: a meta-analytic review. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology : The Official Journal for the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, American Psychological Association, Division 53, 40(4), 630–45. doi:10.1080/15374416.2011.581623 10. Doerfler, L. A., Toscano, P. F., & Connor, D. F. (2008). Separation anxiety and panic disorder in clinically referred youth. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 22(4), 602–11. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.05.009 11. Eapen, V., Dadds, M., Barnett, B., Kohlhoff, J., Khan, F., Radom, N., & Silove, D. M. (2014). Separation anxiety, attachment and inter-personal representations: disentangling the role of oxytocin in the perinatal period. PloS One, 9(9), e107745. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0107745 12. Foley, D. L., Rowe, R., Maes, H., Silberg, J., Eaves, L., & Pickles, A. (2008). The relationship between separation anxiety and impairment. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 22(4), 635–41. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.06.002 13. Kalin, N. H., & Shelton, S. E. (1988). Effects of clonidine and propranolol on separation-induced distress in infant rhesus monkeys. Brain Research, 470(2), 289–95. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3219586 14. Kalin, N. H., Shelton, S. E., & Barksdale, C. M. (1988). Opiate modulation of separation-induced distress in non-human primates. Brain Research, 440(2), 285–92. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3359215 15. Kashani, J. H., & Orvaschel, H. (1990). A community study of anxiety in children and adolescents. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 147(3), 313– 8. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2309948 16. Kearney, C. A., Sims, K. E., Pursell, C. R., & Tillotson, C. A. (2010). Separation Anxiety Disorder in Young Children : A Longitudinal and Family Analysis. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, (October 2014), 37–41. doi:10.1207/S15374424JCCP3204 17. Killgore, W. D. S., & Yurgelun-Todd, D. A. (2005). Social anxiety predicts amygdala activation in adolescents viewing fearful faces. Neuroreport, 16(15), 1671–5. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16189475 18. Klein, D. F. (1993). False Suffocation Alarms, Spontaneous Panics, and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry, 50(4), 306. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820160076009 19. Kossowsky, J., Pfaltz, M. C., Schneider, S., Taeymans, J., Locher, C., & Gaab, J. (2013). The separation anxiety hypothesis of panic disorder revisited: a meta-analysis. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 170(7), 768–81. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12070893 20. Last, C. G., Perrin, S., Hersen, M., & Kazdin, A. E. (1992). DSM-III-R anxiety disorders in children: sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 31(6), 1070–6. doi:10.1097/00004583-199211000-00012 21. Lilienfeld, S. O. (2007). Psychological Treatments That Cause Harm. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 2(1), 53–70. doi:10.1111/j.17456916.2007.00029.x 22. Manicavasagar, V., Silove, D., Curtis, J., & Wagner, R. (2000). Continuities of Separation Anxiety From Early Life Into Adulthood. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 14(1), 1–18. doi:10.1016/S0887-6185(99)00029-8 23. Manicavasagar, V., Silove, D., Marnane, C., & Wagner, R. (2009). Adult attachment styles in panic disorder with and without comorbid adult separation anxiety disorder. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 43, 167–172. doi:10.1080/00048670802607139 24. Milrod, B., Markowitz, J. C., Gerber, A. J., Cyranowski, J., Altemus, M., Shapiro, T., … Glatt, C. (2014a). Childhood separation anxiety and the pathogenesis and treatment of adult anxiety. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(1), 34–43. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13060781 25. Milrod, B., Markowitz, J. C., Gerber, A. J., Cyranowski, J., Altemus, M., Shapiro, T., … Glatt, C. (2014b). Childhood separation anxiety and the pathogenesis and treatment of adult anxiety. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(1), 34–43. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13060781 26. Peleg, Halaby, Whaby (2006). The relationship of maternal separation anxiety and differentiation of self to children’s separation anxiety and adjustment to kindergarten: A study in Druze families. Anxiety Disorders, 20, 973–995. 27. Preter, M., & Klein, D. F. (2008a). Panic, suffocation false alarms, separation anxiety and endogenous opioids. Progress in NeuroPsychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry, 32(3), 603–12. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.07.029 28. Preter, M., & Klein, D. F. (2008b). Panic, suffocation false alarms, separation anxiety and endogenous opioids. Progress in NeuroPsychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry, 32(3), 603–12. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.07.029 29. Roberson-Nay, R., Moruzzi, S., Ogliari, A., Pezzica, E., Tambs, K., Kendler, K. S., & Battaglia, M. (2013). Evidence for distinct genetic effects associated with response to 35% CO₂. Depression and Anxiety, 30(3), 259–66. doi:10.1002/da.22038 30. Shear, K., Jin, R., Ruscio, A. M., Walters, E. E., & Kessler, R. C. (2006). Prevalence and correlates of estimated DSM-IV child and adult separation anxiety disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 163(6), 1074–83. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.6.1074 31. Silverman, W. K., Saavedra, L. M., & Pina, A. A. (2001). Test-retest reliability of anxiety symptoms and diagnoses with the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: child and parent versions. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(8), 937–44. doi:10.1097/00004583-200108000-00016 32. Skowron, E. A., & Friedlander, M. L. (2009). “The Differentiation of Self Inventory: Development and initial validation”: Errata. Journal of Counseling Psychology. doi:10.1037/a0016709 33. Verduin, T. L., & Kendall, P. C. (2003). Differential occurrence of comorbidity within childhood anxiety disorders. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology : The Official Journal for the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, American Psychological Association, Division 53, 32(2), 290–5. doi:10.1207/S15374424JCCP3202_15