wright_Picayune_MS_M..

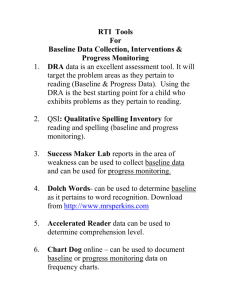

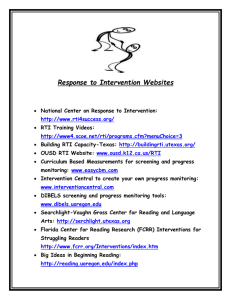

advertisement