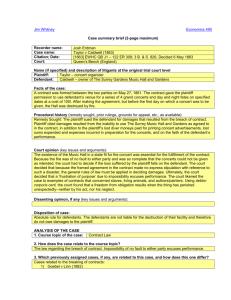

The Duty of Care

advertisement