misrepresentation

advertisement

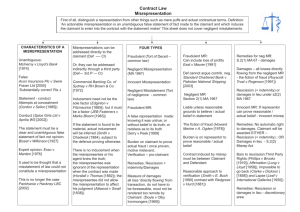

MISREPRESENTATION Law of Contract LW1154 BCL 2005-2006 1 Reading Textbook: Clark chapter 11 Reference: McDermott chapter 13 2 Introduction Where one party made a statement which misled the other before agreeing to the contract … … this may give additional rights to the party who was misled These rights may include: (1) damages (2) a right to escape from the contract 3 We need to consider the blameworthiness of the person who made the statement So we need to distinguish between: Statements made fraudulently Statements made negligently Statements made innocently 4 MISREPRESENTATION ,, Can the statement be taken seriously? 5 Was the statement a serious one? This is really two questions: 1. Did the person who heard it in fact place any reliance on it? 2. Would “the reasonable person” have placed any reliance on it? We must answer “yes” to both if the statement is to give rise to any rights 6 1. Reliance in fact In principle, a statement is relevant only if it was relied on In practice, reliance is presumed if the statement was obviously relevant and important You can rely on several different statements or things at once 7 Example of reliance in fact Cody v. Connolly [1940] 6 Ir Jur 49 Sale of a mare Seller said the mare could do work “of all kinds” Before sale, buyer had a vet inspect the mare Was buyer still relying on seller? O’Byrne J held that he was 8 Example of reliance in fact Gahan v. Bolland (Supreme Court, 20/1/84) Sale of a house Seller said that the new motorway project would not affect it The buyer was a solicitor, and could very easily have checked this But the buyer was still held to have relied on the seller’s statement 9 Statement not believed But if the statement is not believed by those who hear it … … it is impossible to say that they relied on it e.g. Colthurst v. Colthurst [2000] IEHC 14 10 2. Reliance in law It is not enough to show that a statement was relied on … … if the statement was one that no reasonable person would rely on There is a considerable case law on what reasonable people are supposed to rely on 11 2. Reliance in law The cases where “reliance in law” has been doubted fall into 4 rough groups: Mere sales talk Statements of opinion Statements of intention Statements of law 12 “Mere sales talk” If reasonable people would think they were hearing mere sales talk … … then they are not entitled to rely on it So mere sales talk cannot amount to a misrepresentation 13 Example 1 Dimmock v. Hallett (1866) LR 2 Ch 21 Sale of farming land The seller described it as “fertile and improvable” The court said this was “a mere flourishing statement” … … and refused to treat it as a misrepresentation 14 Example 2 Smith v. Lynn (1954) 85 ILTR 57 A house was advertised as being “in excellent structural repair” Both P and D inspect it and bid for it D bids higher, but 6 weeks after buying tries to resell it D re-uses the old advert P buys from D 15 Example 2 Smith v. Lynn (1954) 85 ILTR 57 Could P reasonably rely on the advert? Curran J held that he could not P had inspected the house, so should not have relied on the advert “It is common knowledge that … one usually finds in such advertisements rather flourishing statements” 16 Statements of opinion If one side makes a mere statement of opinion … … the other side should not treat it as a factual statement … … and usually cannot reasonably pay it attention at all 17 Example Bisset v. Wilkinson [1927] AC 177 Sale of farm land Seller estimated that the land could support 2,000 sheep However, this was obviously a mere statement of opinion … … and so the buyer could not sue when the estimate was proved overoptimistic 18 An exception In Bisset the parties were farmers So they were expected to rely on their own opinions, not those of other farmers It may be different if the opinion comes from someone very knowledgeable … … so that it is reasonable for the other to rely heavily on the opinion 19 An exception So an apparent expert giving their opinion may be making an implied statement of fact … … to the effect “I have reasonable grounds for the opinion I am giving” If the expert has no such reasonable grounds, then there is a misrepresentation 20 Example 1 Irish Times 12/12/97 Doheny v. Bank of Ireland A bank described a client as “respectable and trustworthy” But she had a record of dishonesty So although “respectable and trustworthy” is a matter of opinion … … nonetheless a misrepresentation was established 21 Example 2 Esso v. Mardon [1976] QB 801 Mardon was negotiating for an Esso franchise at a petrol filling station Esso’s economist made an estimate of the amount of petrol it would sell Mardon bought the franchise But the estimate turned out to be over-optimistic 22 Example 2 Esso v. Mardon [1976] QB 801 The court of appeal held that: The estimate was mere opinion But it involved an implied assertion that it had been made carefully In fact, the economist had made a basic error Therefore the estimate amounted to a misrepresentation 23 Statements of intention If I say “I intend to do X” … … then that is a misrepresentation if I do not intend to do X However, a statement of intention is not the same thing as a promise … … so it is not enough simply to show that I failed to do X 24 “… the state of a man’s mind is as much a fact as the state of his digestion” Edgington v. Fitzmaurice (1885) 29 ChD 459 (Bowen LJ) 25 Statements of intention So a false statement of intention can form the basis of an action in misrepresentation … … so long as the speaker never really had that intention But a simple failure to carry through a stated intention is not actionable 26 Statements of law It is often said that mis-statements of law are not actionable … … perhaps because “everyone is presumed to know the law” The rationale of the rule is unclear, and it is often criticised But the rule is very well established e.g. Doolan v. Murray (Keane J, 21/12/93) 27 Statements of law - exception Despite the traditional rule, some statements of law are actionable: Fraudulent statements of law Statements of foreign law Statements about private rights 28 MISREPRESENTATION Silence and misrepresentation 29 Silence – general rule Most cases assume that there is some statement or representation … … rather than a simple failure to speak The general rule is that some statement is needed … … and that silence is not enough … … even if it is misleading 30 Example Kennedy v. Hennessy (1906) 40 ILTR 84 Sale of heifers at a fair One of the heifers was in fact in calf, and so of low value But nothing had been said on that subject, either on or before the sale Gibson J held that there was no misrepresentation 31 Silence – exceptions In 3 cases, silence will be treated as a misrepresentation 1. Where an accurate but confusing statement has been made 2. Where a statement was true when made, but becomes false 3. Where there is a legal duty to speak 32 Confusing statements Where a true statement is made … … but that statement is confusing or misleading unless more is said … … there is a duty to clear up the confusion A failure to speak amounts to a misrepresentation 33 Example Notts Brick v. Butler (1886) 16 QBD 778 Sale of land The solicitor said that he wasn’t aware of any covenants on the land But he hadn’t looked at the documents This amounted to a misrepresentation 34 Statement true when made If a statement is true at the time it is made … … but becomes untrue before the contract is finally agreed … … a failure to admit this amounts to a misrepresentation 35 Example Spice Girls v. Aprilia [2000] EMLR 478 Negotiations for product endorsement by the Spice Girls The 5 members of the group appeared for a photo shoot … … but kept back the information that one member (Gerry Halliwell) would soon be leaving 36 Example Spice Girls v. Aprilia [2000] EMLR 478 Arden J held that: Gerry Halliwell’s departure removed all commercial value from the picture shoot Failure to reveal the truth was misleading Allowing her to take part amounted to a misrepresentation 37 Duty to speak If the law imposes a duty to reveal certain facts or matters … … then a failure to speak amounts to a misrepresentation There are no such general duties applicable to all contracts … … but there are many applicable to particular types of contract 38 Example 1 Sales of land The duties of the seller of property are prescribed in cases and statute They certainly include obligations to reveal defects in title, and covenants binding the land So silence on these points amounts to a misrepresentation 39 Example 2 Insurance contracts Those seeking insurance have a general duty to disclose all material facts A material fact is one which would influence a prudent insurer in deciding: whether to accept the insurance, or in setting the premium to be paid 40 Summary and recap There must be: reliance in fact, and reliance in law There must also be: a positive statement, or silence which is equivalent to a statement 41 Misrepresentation Remedies for misrepresentation Introduction 42 3 ways in which a plaintiff can use misrepresentation 1. P can argue that D guaranteed the truth of the statement 2. P can argue that the making of the statement was a tort or wrong, deserving compensation 3. P can seek to escape from (= “rescind”) the contract 43 Guaranteeing the statement P argues that when the statement was made … … the maker promised that it was true … … and so is in breach of contract if it is not If successful, this may lead to an award of damages 44 A mis-statement as a wrong P argues that the making of the statement was a wrong … … which harmed P’s financial interests … … and so should be compensated This argument can only be made if the person who made the statement was at fault in some way 45 Rescission of the contract P argues that the contract was only made because D misled P … … and so P should be allowed to escape from the contract when the truth becomes known This is the weakest of the three arguments, as it is hard to unravel a partially-performed contract 46 3 different approaches? Can P combine two or more approaches in one action? In theory yes, but:- The courts will not allow double compensation for the same wrong Either the contract remains in place or it doesn’t 47 MISREPRESENTATION 1. Statements which have been guaranteed to be true 48 Guarantee – Basic principle If a statement is made during contractual negotiations … … and the maker of the statement seems to be encouraging reliance on the statement … … then they may be held to have promised or guaranteed its truth … … and so can be sued if it is false 49 Example 1 Phelps v. White (1881) 7 LR (I) 160 Sale of land, on which there were some trees The seller said that the right to the trees was included in the sale In fact, it was not The buyer was held able to sue for the value of the timber 50 Implicit representations Sometimes the representation is only implicit in what is said But if the implication is obvious … … and the invitation to rely is clear … … then an action may lie 51 Example McRae v. CDC (1951) 84 CLR 377 Sale of a tanker wreck Seller gave very precise details of its location … … and so was held to be guaranteeing its existence Seller was liable for buyer’s expenses thrown away in looking for it 52 Is there a guarantee? Relevant factors (though none is conclusive) include: Whether there was a clear statement or promise Whether the other party thought the statement important or relevant Whether the other party could find out the truth for themselves 53 Remedy? The claim is for a broken promise (that the statement was true) … … and so the usual remedy is an action for damages 54 Calculation of damages? Contract damages are usually given on the “expectation” measure … i.e. we ask, How would P have gained if the promise had been kept So the usual measure here is, How much would P have gained if the statement had been true e.g. Phelps v. White 55 Calculation of damages? Sometimes, this “expectation” measure is hard to calculate … … and the court allows instead the “reliance” measure i.e. The amount thrown away in reliance on the statement e.g. McRae v. CDC 56 Summary Someone complaining of a misrepresentation has to show: either 1. that statement was promised to be true or 2. that the making of the statement was a legal wrong or 3. that the statement gives grounds for rescission 57 MISREPRESENTATION 2. Statements tortiously (wrongly) made 58 “Tortiously” Sometimes the making of a statement is a “tort” … … i.e. a personal wrong against the person hearing it … … who can sue for loss resulting from the statement This involves proof that the maker of the statement was at fault 59 3 relevant torts 1. The tort of “deceit” P must prove D knew of the falsity 2. The tort of “negligent misstatement” P must prove D was negligent 3. The statutory misrepresentation tort D must prove lack of negligence 60 The tort of deceit A tort of deliberately causing harm It can only be used where D can be proved not to have believed what s/he was saying 61 The tort of deceit: elements If D makes a false statement and intends that P should act on it and knows it is false (or doesn’t care whether it is true or not) and P, acting on it, suffers loss Then P can sue D for the loss 62 Example Carbin v. Somerville [1933] IR 226 Sale of a house The seller told the buyer that the house was dry In fact, the house was thoroughly and hopelessly damp FitzGibbon J found that the seller must have known this all along … … so the buyer could sue in deceit 63 Knowledge of falsity? P must establish either that D knew the statement was untrue … … or that D was “reckless” in making the statement If D had no idea whether the statement was true or not … … then “recklessness” is proved 64 Example Moran v. Orchanda Ltd (HC, 25/5/00) Sale of a pub The seller gave the buyer figures for the last 2 years’ turnover But the seller didn’t really know if the figures were accurate McCracken J held that the figures were given recklessly 65 Remedy P is complaining that s/he has been injured by D’s false statement … … so the remedy is damages in compensation 66 Measure of damages The basic measure is the “reliance” measure … … i.e. the amount P threw away in reliance on the statement The test is to compare P’s financial condition as it is … … with how it would have been if D had never made the statement 67 Example Fenton v. Schofield (1966) 100 ILTR 69 Sale of a house with a fishery Seller made fraudulent statements as to the number of fish caught Buyer paid seller £27,000 in all In fact, the property was worth only £22,000 So damages were £5,000 68 Damages – extent D is liable for all the loss caused by the fraudulent statement even if D did not intend loss to P even if some of it is rather distant or “remote” from the statement even if the loss would have been hard to predict or foresee beforehand 69 Example Smith v. Scrimgeour [1997] AC 254 D tricks P into buying a large block of shares in a company P buys at 82p per share, when the market price is 78p Then The the company suffers a disaster share price falls to 44p What is the measure of damages? 70 Example Smith v. Scrimgeour [1997] AC 254 D argues: we tricked P into paying 82p for shares then worth 78p So the loss is only 4p a share The subsequent crash was not D’s fault … … and so shouldn’t affect the damages 71 Example Smith v. Scrimgeour [1997] AC 254 But the House of Lords held: D are responsible for all the loss their false statement caused P paid 82p, but the shares fell to 44p So D are liable for 38p per share Different if P had had a real chance to dis-invest before the crash 72 Negligent misstatement This is a tort of carelessly causing harm It can only be used where D owed P a duty to be careful (a “duty of care”), and D can be shown to have been careless 73 The elements of the tort If P relies on D’s skill or judgment and D ought reasonably to know this and D then makes a false statement and D was negligent in so doing and P suffers loss as a result Then P can sue D for loss suffered 74 Not confined to contract The doctrine is not confined to cases of contracting parties If both parties are equally skilled, it doesn’t apply at all … … as it would be hard to show that one relied on the other’s skill But it applies if one party can be shown to be relying on the other 75 Example Doran v. Delaney [1999] 1 IR 303 Sale of house Buyers asked whether sellers knew of any disputes related to the house Seller’s solicitor said they knew of none This was incorrect and careless Geoghegan J found liability 76 No duty if disclaimer made If D states that P should not rely on what D says … then P should not rely … and D is not liable if P does so Ditto if D says the statement is made “without responsibility” … as in Hedley Byrne v. Heller [1964] AC 465 77 Duty is owed to individuals P must prove that D owed a duty to P It is not enough that D owed a duty to someone else … … or that the statement was a breach of a duty owed to someone else 78 Example Stafford v. Mahony [1980] ILRM 53 An auctioneer advised a client that a particular house was a good buy The client passed this tip on to his brother The brother bought the house, and suffered financial loss as a result Doyle J held that the auctioneer did not owe a duty to the brother 79 Measure of damages The basic measure is the “reliance” measure … … i.e. the amount P threw away in reliance on the statement The test is to compare P’s financial condition as it is … … with how it would have been if D had never made the statement 80 Damages – extent However, D is not liable for all the loss caused by the false statement D is not liable for loss which is too distant or “remote” from the statement D is not liable for a loss which could not be foreseen beforehand 81 Example Naughton v. O’Callaghan [1990] 3 AER 191 Sale of a colt, buyers hoping it would be a good racer Sellers misrepresented its ancestry Buyers spent £15,000 to train it … … but eventually realised they were wasting their money How were damages to be measured? 82 Example Naughton v. O’Callaghan [1990] 3 AER 191 Sellers argued: The buyers spent £31,500 to acquire the colt … … which was really worth £25,000 So damages were just £6,500 83 Example Naughton v. O’Callaghan [1990] 3 AER 191 But Waller J held: The buyers spent £31,500 + £15,000 in training fees … … to get a colt worth £1,500 So damages were (31,500 + 15,000 – 1,500) = £45,000 Might get a different result if buyers had appreciated the truth earlier 84 The statutory tort Contractual misrepresentation has been made a tort by statute viz. Sale of Goods and Supply of Services Act 1980 s.45 Like the common law tort, it relates to statements made carelessly … … but where it applies, it is a rather wider liability 85 The statutory tort Recall that if a statement is made fraudulently … … then someone who relies on it can sue for loss they suffer Under the statutory tort, a statement in contract negotiations will be presumed to be fraudulent … … unless its maker can prove it was made carefully 86 The statutory tort - elements Where a contract is made: after a false statement by one party and there would have been liability if the statement had been fraudulent Then there is liability for loss suffered, as if there were fraud unless the statement was made carefully 87 2 reasons why this is awkward The statute introduces a fiction of fraud … … deeming people to be “fraudulent” when they were only careless Only certain types of contracts are caught by the statute … viz. sale of goods, hire of goods, hire purchase, and supply of services 88 A broad liability So where a false statement is made by one party to the contract … … and loss resulted to the other … … the burden of proof shifts to the person who made the statement … …who must show that the statement was made carefully 89 Example O’Donnell v. Truck Sales [1997] 1 IRLM 466 Sale of Volvo mechanical shovels Sellers made mis-statements as to their standard and performance There ... was also fault by the buyer … but Moriarty J found liability (His holding was reversed on grounds irrelevant here, [1998] 4 IR 191) 90 Measure of damages The basic measure is the “reliance” measure … … i.e. the amount P threw away in reliance on the statement The test is to compare P’s financial condition as it is … … with how it would have been if D had never made the statement 91 Damages – extent Because the statement is deemed to be made fraudulently:D is liable for all the loss caused by the false statement even if some of it is “remote” or unforeseeable (Royscot Trust v. Rogerson [1991] 3 AER 294) 92 Summary Someone complaining of a misrepresentation has to show: either 1. that statement was promised to be true or 2. that the making of the statement was a legal wrong or 3. that the statement gives grounds for rescission 93 MISREPRESENTATION 3. Statements giving rise to a right to escape (or “rescind”) the contract 94 The right to rescission If a contract was made as the result of a misrepresentation … … then the party who is misled may seek to escape the contract (“rescission”) The court will then attempt to restore both parties to their original positions 95 Does fault matter? In principle, rescission is available whether the mis-statement was fraudulent, negligent or innocent However, unwinding a contract often involves difficult issues of fairness … … and a fraudulent party may be treated much more harshly than a negligent or innocent party 96 What is “rescission” “Rescission” means restoring the parties to their positions before the contract was made Each is made to return to the other what they received under the contract Other gains and losses are ignored 97 Example Northern Bank v. Charlton [1979] IR 149 A bank But financed a take-over bid the bank had committed fraud When the investors sought rescission, they had to return money received from the bank … … but not shares received from elsewhere 98 Rescission + damages? Rescission simply means unwinding the contract It does not include an award of damages If the innocent party suffers a loss which rescission does not cure … … the loss will have to be claimed on tort principles 99 Rescission + indemnity? If one side undertook some legal responsibility under the contract … … but can then rescind the contract for misrepresentation … … the court may make the other party pay the expense involved This is called “rescission with indemnity” 100 Example Whittington v. Hayne (1900) 82 LT 49 Farm tenant undertook to keep the premises clean The landlord had misrepresented their cleanliness … … so that keeping the premises clean was very costly On rescission, the tenant was indemnified against this cost 101 Rescission is available for any misrepresentation at all But there are 5 bars: 1. Impossibility of rescission 2. Intervention of 3rd party rights 3. Affirmation of the contract 4. Delay in seeking a remedy 5. Contract is already fully executed 102 Bar: Impossibility If it is no longer possible for both sides to restore what they received under the contract … … then rescission is not available But “impossible” is a flexible term The courts do not rigorously insist on this bar if there was fraud 103 Bar: 3rd party rights Rescission will not be ordered if it interferes with the rights of a bona fide 3rd party purchaser So if a buyer tells lies to get a low price from a seller … … and buyer then re-sells the property to an innocent 3rd party … … rescission will not be ordered 104 Bar: Affirmation A right to rescind can be lost by a definite decision not to do so If a victim of misrepresentation realises that s/he has been misled … … yet nonetheless declares that the contract remains in force … … then s/he cannot retract this 105 Bar: Delay The right to rescind can be lost by too much delay in seeking it But this rule is not applied harshly to victims of fraud (e.g. Carbin v. Somerville, 12 years’ delay) Innocent misrepresentation is another matter 106 Bar: Contract fully executed If the contract has been performed on both sides … … then it is too late to set it aside This is a rather harsh rule … … which has been abolished in other common law jurisdictions 3 exceptions are recognised 107 Bar: Contract fully executed The exceptions: 1. Fraudulent misrepresentations 2. Total failure of consideration 3. The contract is within the Sale of Goods and Supply of Services Act 1980 (the definition section is s 43) 108 Remedies short of rescission Rescission is often too drastic a remedy In cases of elaborate contracts, complete rescission is too complicated to carry out Sometimes, the courts resort to lesser remedies 3 distinct doctrines 109 1. Enforcement + abatement Where the misrepresentation is relatively insignificant … … and does not change the overall character of the contract … … the court may force the party who was misled to perform the contract … … but with an abatement of price 110 Example Connor v. Potts [1897] 1 IR 534 Sale of land, at £12 10s per acre The seller (innocently) over-stated the amount of land Chatterton VC ordered the buyer to perform … … but said he need only pay for the acreage he was actually getting 111 2. Damages in lieu If the court would be entitled to allow rescission for misrepresentation … … but considers that justice would be better served by simply awarding damages … … then the court can do so 112 This power is from the Sale of Goods and Supply of Services Act 1980 s 45(2) It does not apply to fraudulent misrepresentations … … or if the contract is not one to which the 1980 Act applies It is entirely unclear how the damages are measured 113 3. Partial rescission Sometimes a party to a contract can only say that s/he was misled in some respects e.g. s/he is willing to guarantee some of the debts of another person … … but is tricked into signing a document guaranteeing them all Can s/he then escape the contract entirely? 114 The Australians allow partial rescission (Vadasz v. Pioneer Concrete (1995) 184 CLR 102) But the English say that rescission “is an all-or-nothing process” (TSB Bank v. Camfield [1995] 1 AER 951) The Irish courts say: ???? 115 MISREPRESENTATION Exclusion of liability for misrepresentation 116 Exclusion of liability Sometimes the contract itself lays down rules governing complaints of misrepresentation The contract may even purport to exclude any such claim entirely But is it possible to exclude liability for misrepresentation? 117 Exclusion of liability Liability for fraud cannot be excluded So if a contract provides that one party “must verify all representations for himself” … … this does not stop him from suing for a fraud by the other party (Pearson v. Dublin Corporation [1907] AC 351) 118 Exclusion of liability But the general rule is that liability for innocent misrepresentation can be excluded … … so long as clear words to that effect are included in the contract 119 Example Dublin Port v. Brittania Dredging [1968] IR 136 D undertook dredging work for P D “shall be deemed to have inspected the site” and P “shall not be liable for any misrepresentation or lack of information” This protected P from a later charge of innocent misrepresentation 120 The position by statute Where Sale of Goods and Supply of Services Act 1980 applies … … then liability for innocent misrepresentation can only be excluded if it is fair and reasonable to do so (s 46) It is for the party relying on the exclusion to demonstrate that it is a reasonable one 121 That’s all on misrepresentation 122 123