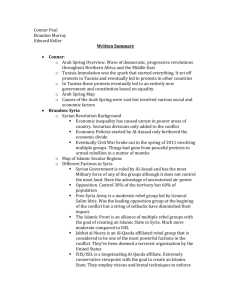

Arab Spring File

advertisement

Understanding the Revolutions of 2011 by Jack O. Goldstone The Post-Islamist Revolutions by Asef Bayat A political cartoon by Carlos Latuff depicting President of Egypt Hosni Mubarak facing the Tunisian knock-on domino effect. The Arab Spring 2011 saw dramatic changes in the Arab world’s governance landscape. Unprecedented popular demonstrations in Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya led to the overturning of a half a century of autocratic rule in North Africa. Tunisian President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali fled to Saudi Arabia on 14 January following the Tunisian revolution protests. In Egypt, President Hosni Mubarak resigned on 11 February 2011 after 18 days of massive protests, ending his 30-year presidency. The Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi was overthrown on 23 August 2011, after the National Transitional Council (NTC) took control of Bab al-Azizia. He was killed on 20 October 2011. The Arab Spring There has also been civil uprisings in Bahrain, Syria, and Yemen, the latter resulting in the resignation of the Yemeni prime minister; major protests in Algeria, Iraq, Jordan, Morocco, and Oman; and minor protests in Kuwait, Lebanon, Mauritania, Saudi Arabia, Sudan. It was sparked by the first protests that occurred in Tunisia on 18 December 2010 following Mohamed Bouazizi's burning himself in protest of police corruption and ill treatment. These protests, demanding greater political freedom, economic opportunity, and an end to systemic corruption, have resonated deeply across the region, sparking calls for change throughout the Arab world (among others in Syria, Bahrain, and Yemen). Other Arab states, especially the monarchies, have so far warded off calls for change with seeming success, using the familiar mix of coercion, co-option and promises. However, this does not necessarily mean that they were not affected at all. A status report on the Arab awakening (As of July 2011) Source: The Economist – 14 July 2011 While there are major cultural, economic, and geographic differences, the experiences in North Africa are serving as models for the rest of Africa too. In the months following the launch of the Arab Spring, there have been protests in more than a dozen African capitals calling for greater political participation, transparency, and adherence to the rule of law. Arab political language is changing: “The new slogans are about equitable distribution of wealth, defeating nepotism and corruption, freedom of expression and assembly, all of which are rights meant to restore self-respect and render to people their due sense of dignity.” One of the remarkable aspects of the prospective democratic transitions in North Africa and the Middle East is that it has taken so long. Intro With the exception of Central Asia, the Arab world is the last major region to start down the democratic path. Since Intro “the third wave” of global democratization (which started in the mid1970s with the toppling of the dictator of Portugal), dozens of countries with all kinds of authoritarian political systems—monarchies, oligarchies, military dictatorships, one-party regimes—shifted into the democratic camp. As most of the world was transformed, however, one area remained frozen in time: the Arab Middle East. Triggers and Drivers Many of the challenges, frustrations, and unmet aspirations in the Arab world have existed for years. Why then is there such agitation for reform now? In other words, what has changed? Triggers and Drivers Nobody really knows, of course. No one thought Tunisia was on the verge of an eruption; that the upheaval would spread from Tunisia to Egypt; and that the shocks would reverberate around the Middle East. The old regimes themselves were taken aback by the force and speed of the uprisings. Even traditional opposition parties were behind the curve, often remaining hesitant well after newer popular protest movements sprang up and seized the moment (with the help of social media and communications technologies that proved to be a new and powerful political tool). How did it start? The uprising began in December 2010, when a fruit vendor, Mohamed Bouazizi, set himself on fire in the town of Sidi Bouzid (Tunisia) to protest his lack of opportunity and the disrespect of the police. How did it start? Tunisia, therefore, can be considered as the pioneer of “the revolutionary movements as the Tunisians were the first to break the barrier of fear, which constituted the major obstacle in the face of unleashing popular fury and resentment over deteriorating economic, social and political conditions which needed only a spark to explode forth”. “The Tunisian revolution was the catalyst that instigated the Egyptian revolt and uprisings in other countries. Despite the limited significance of Tunisia in the regional Arab system, its role in breaking the barrier of fear was of paramount importance, which should not be underestimated, and which exceeded Tunisia’s traditional role in the regional scheme”. Triggers and Drivers Rising food prices High Unemployment Rate (Especially youth Unemployment) Frustration with closed, corrupt, unresponsive political systems. Increasing income inequality Necessary Conditions for a Revolution For a revolution to succeed, a number of factors have to come together: 1) The government must appear so irremediably (impossible to cure or put right) unjust or incompetent that it is widely viewed as a threat to the country's future. Necessary Conditions for a Revolution 2) Elites (especially in the military) must be alienated from the state and no longer willing to defend it. Necessary Conditions for a Revolution 3) A broad-based section of the population, spanning ethnic and religious groups and socioeconomic classes, must mobilize. Necessary Conditions for a Revolution 4) International powers must either refuse to step in to defend the government or constrain it from using maximum force to defend itself. Necessary Conditions for a Revolution Revolutions rarely triumph because these conditions rarely coincide. This is especially the case in traditional monarchies and one-party states, whose leaders often manage to maintain popular support by making appeals to respect for royal tradition or nationalism Necessary Conditions for a Revolution Elites, who are often enriched by such governments, will only forsake them if their circumstances or the ideology of the rulers changes drastically. Necessary Conditions for a Revolution And in almost all cases, broad-based popular mobilization is difficult to achieve because it requires bridging the different interests of the urban and rural poor, the middle class, students, professionals, and different ethnic or religious groups. History is full of student movements, workers' strikes, and peasant uprisings that were easily put down because they remained a revolt of one group, rather than of broad coalition’s Necessary Conditions for a Revolution Finally, other countries have often intervened to save embattled rulers in order to stabilize the international system. (i.e. in support of their opposition to Communists/I ran/ Radical Islamist Groups etc.) (A Recent Example: Bahrain) The Sultanistic Regimes Such regimes arise when a national leader expands his personal power at the expense of formal institutions. How did the sultanistic regimes manage to resist change? The Sultanistic Regimes Sultanistic dictators appeal to no ideology and have no purpose other than maintaining their personal authority. They may preserve some of the formal aspects of democracy - elections, political parties, a national assembly, or a constitution. However, they rule above them by installing their supporters in key positions and sometimes by declaring states of emergency, which they justify by appealing to fears of external (or internal) enemies. The Sultanistic Regimes Behind the scenes, such dictators generally accumulate great wealth, which they use to buy the loyalty of supporters and punish opponents. They also seek relationships with foreign countries, promising stability in exchange for aid and investment. The Sultanistic Regimes The leaders control their countries' military elites by keeping them divided. Typically, the security forces are separated into several commands (army, air force, police, intelligence) - each of which reports directly to the leader. The Sultanistic Regimes To keep the masses depoliticized and unorganized, sultans control elections and political parties and pay their populations off with subsidies for key goods, such as electricity, gasoline, and foodstuffs. When combined with surveillance, media control, and intimidation, these efforts generally ensure that citizens stay disconnected and passive. The Sultanistic Regimes By following this pattern, politically skillful sultans around the world (sultanistic dictatorships are not unique to the Arab world: Mexico, Indonesia and Nicaragua, among others had similar regimes) have managed to accumulate vast wealth and high concentrations of power. But as the new generation of sultans in the Middle East has discovered, power that is too concentrated can be difficult to hold on to. Inherent Vulnerabilities (Essential Weaknesses of Sultanistic Dictatorships Sultans must strike a careful balance between self- enrichment and rewarding the elite: If the ruler rewards himself and neglects the elite, a key incentive for the elite to support the regime is removed. Inherent Vulnerabilities (Essential Weaknesses of Sultanistic Dictatorships Meanwhile, as the economy grows and education expands, the number of people with higher aspirations and a keener sensitivity to the intrusions of police surveillance and abuse increases. Inherent Vulnerabilities (Essential Weaknesses of Sultanistic Dictatorships And if the entire population grows rapidly while the lion's share of economic gains is hoarded by the elite, inequality and unemployment surge as well. Inherent Vulnerabilities (Essential Weaknesses of Sultanistic Dictatorships As the costs of subsidies and other programs the regime uses to appease citizens rise, keeping the masses depoliticized places even more stress on the regime. Inherent Vulnerabilities (Essential Weaknesses of Sultanistic Dictatorships If protests start, sultans may offer reforms or expand patronage benefits to head off escalating public anger. These concessions are generally ineffective once people have begun to clamor for ending the sultan's rule. Inherent Vulnerabilities (Essential Weaknesses of Sultanistic Dictatorships By dividing their command structure, the sultan may reduce the threat posed by the security services. But this strategy also makes them more prone to defections in the event of mass protests. Lack of unity leads to splits within the security services; meanwhile, the fact that the regime is not backed by any appealing ideology or by independent institutions ensures that the military has less motivation to put down protests. Inherent Vulnerabilities (Essential Weaknesses of Sultanistic Dictatorships Much of the military may decide that the country's interests are better served by regime change. If part of the armed forces defects the government can unravel with astonishing rapidity. The Arab Spring The revolutions unfolding across the Middle East represent the breakdown of increasingly corrupt sultanistic regimes. Although economies across the region have grown in recent years, the gains have bypassed the majority of the population, being amassed instead by a wealthy few. The Arab Spring Mubarak and his family reportedly built up a fortune of between $40 billion and $70 billion, and 39 officials and businessmen close to Mubarak's son Gamal are alleged to have made fortunes averaging more than $1 billion each. The Arab Spring Fast-growing and urbanizing populations in the Middle East have been hurt by low wages and by food prices that rose by 32 percent in the last year alone, according to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization. But it is not simply such rising prices, or a lack of growth, that fuels revolutions; it is the persistence of widespread and unrelieved poverty amid increasingly extravagant wealth. The Arab Spring Discontent has also been strengthened by high unemployment, which has stemmed in part from the sharp increase in the Arab world's young population. Not only is the proportion of young people in the Middle East extraordinarily high, but their numbers have grown quickly over a short period of time. Since 1990, youth population aged 15-29 has grown by 50%in Libya and Tunisia, 65%in Egypt, and 125%in Yemen. The Arab Spring Many of these young people have been able to go to university, especially in recent years. Indeed, college enrollment has soared across the region in recent decades, more than tripling in Tunisia, quadrupling in Egypt, and expanding tenfold in Libya. The Arab Spring In both Tunisia and Egypt, the military had seen its status eclipsed recently. In both countries military resentments made the military less likely to crack down on mass protests; officers and soldiers would not kill their countrymen just to keep the Ben Ali and Mubarak families and their favorites in power. A similar defection among factions of the Libyan military led to Qaddafi's rapid loss of large territories. Monarchies The region's monarchies are more likely to retain power. This is not because they face no calls for change. In fact, Morocco, Jordan, Oman, and the Persian Gulf kingdoms face the same demographic, educational, and economic challenges that the sultanistic regimes do, and they must reform to meet them. But the monarchies have one big advantage: Their political structures are flexible. Modern monarchies can retain considerable executive power while ceding legislative power to elected parliaments. Monarchies In times of unrest, crowds are more likely to protest for legislative change abandonment of the monarchy. than for This gives monarchs more room to maneuver to pacify the people. After Revolutions Some Western governments, having long supported Ben Ali and Mubarak as bulwarks against a rising tide of radical Islam, now fear that Islamist groups are poised to take over. Yet the historical record of revolutions in sultanistic regimes should somewhat alleviate such concerns. Not a single sultan overthrown in the last 30 years has been succeeded by an ideologically driven or radical government. Rather, in every case, the end product has been a flawed democracy: often corrupt and prone to authoritarian tendencies, but not aggressive or extremist. After Revolutions This marks a significant shift in world history. Between 1949 and 1979, every revolution against a sultanistic regime (in China, Cuba, Vietnam, Cambodia, Iran, and Nicaragua) resulted in a communist or an Islamist government. Yet since the 1980s, neither the communist nor the Islamist model has had much appeal. Both are widely perceived as failures at producing economic growth and popular accountability; the two chief goals of all recent anti-sultanistic revolutions. After Revolutions The United States and other Western nations have little credibility in the Middle East given their long support for sultanistic dictators. Any efforts to use aid to support certain groups or influence electoral outcomes are likely to arouse suspicion After Revolutions: The Role of West What the revolutionaries need from Westerners is vocal support for the process of democracy, a willingness to accept all groups that play by democratic rules, and a positive response to any requests for technical assistance in institution building. After Revolutions: Risks Ahead The greatest risk that Tunisia and Egypt now face is an attempt at counterrevolution by military conservatives, a group that has often sought to claim power after a sultan has been removed. After Revolutions: Risks Ahead The other main threat to democracies in the Middle East is war. Historically, revolutionary regimes have hardened and become more radical international conflict. in response to After Revolutions: Egypt June 2012, Hosni Mubarak was found guilty of complicity in the murders of the protestors and sentenced to life imprisonment. 24 June 2012, Islamist Mohammed Morsi won the presidential election. 12 August 2012: President Morsi ousted Egypt's military leadership and assumed legislative powers. After Revolutions: Egypt 12 October 2012: Critics and supporters of Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi clashed in Cairo's Tahrir Square on 12 October 2012 in a small but potent rally, as liberal and secular activists erupted with anger accusing the Muslim Brotherhood of trying to take over the country. After Revolutions: Egypt November 2012: Liberal and secular groups walked out of the constitutional constituent assembly because they believed that it would impose strict Islamic practices, while members of the Muslim Brotherhood supported Morsi. Protesters battled the police demanding political reforms and the prosecution of officials blamed for killing demonstrators as well as to protest against Morsy and the growing influence of the Muslim Brotherhood. After Revolutions: Egypt 22 November 2012: Morsi issued a constitutional declaration which extended his powers : “The president is authorised to take any measures he sees fit in order to preserve the revolution, to preserve national unity or to safeguard national security”. He eventually rescinded it in the face of popular protests. Meanwhile a new constitution is drafted which human rights groups and international experts said was full of holes and ambiguities . After Revolutions: Egypt 2012 December- Islamist-dominated constituent assembly approved draft constitution that supported the role of Islam and restricted freedom of speech and assembly. Public approved it in a referendum, prompting extensive protest by secular opposition leaders, Christians and women's groups. In January 2013, more than 50 people are killed during days of violent street protests. The army chief warned that political strife is pushing the state to the brink of collapse. After Revolutions: Egypt In February 2013, hundreds of police officers in Egypt shut down headquarters of Interior Ministry in at least seven provincial capitals across country in series of protests against what they call political exploitation by government of Pres Mohamed Morsi. On Mar. 23, 2013, dozens of people are injured when thousands of supporters and opponents of Egypt's ruling Muslim Brotherhood clash outside group's Cairo headquarters. After Revolutions: Egypt On May. 2, 2013, Egyptian authorities jail anti-Islamist activist Ahmed Douma on charges that include insulting Pres Mohamed Morsi. (there are various similar incidents). On May 8, 2013, president Mohamed Morsi swears in nine new cabinet members in reshuffle that increases role of Islamists in upper ranks of government. After Revolutions: Tunisia The Tunisian military ousted Zine El Abidine Ben Ali on 14 Jan 2011. On 14 January, Ben Ali dissolved his government and declared a state of emergency. Officials said the reason for the emergency declaration was to protect Tunisians and their property. People were also barred from gathering in groups of more than three, otherwise courting arrest or being shot if they tried to run away. Ben Ali also called for an election within six months to defuse demonstrations aimed at forcing him out. The military took control of the airport and closed the country's airspace. After Revolutions: Tunisia On the same day, Ben Ali fled the country for Malta under Libyan protection and landed in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, after France rejected a request for the plane to land on its territory. Saudi Arabia gave him asylum. On the morning of 15 January, Tunisian state TV announced that Ben Ali had officially resigned his position. After Revolutions: Tunisia A commission to reform the constitution and current law in general has been set up . After Bin Ali left, gun battles took place near the Presidential Palace between the Tunisian army and elements of security organs loyal to the former regime. The Tunisian army was reportedly struggling to assert control. After Revolutions: Tunisia On 23 October 2011, Tunisians voted for the first time post-revolution. The election appointed members to a Constituent Assembly charged with rewriting Tunisia's Constitution. The formerly-banned Islamic party Ennahda won by capturing 41% of the total vote. Ehnada rules Tunisia in a “troika” coalition with two center-left parties. 2011 December - Human rights activist Moncef Marzouki is elected president by the constituent assembly, Ennahda leader Hamadi Jebali is sworn in as prime minister. After Revolutions: Tunisia 2012 June - Former president Ben Ali is sentenced to life in prison over the killing of protesters in the 2011 revolution. He is living in Saudi Arabia, which refuses to extradite him. 2012 August - Thousands protest in Tunis against moves by Islamist-led government to reduce women's rights. Draft constitution refers to women as "complementary to men", whereas 1956 constitution granted women full equality with men. After Revolutions: Tunisia 2013 February - Prime Minister Jebali resigned after his ruling Islamist Ennahda party rejects his proposals to form a government of technocrats after the killing of an opposition anti-Islamist leader. Since 14 March 2013, the prime minister is Ali Laarayedh . He represents the Ennahda Movement. Ennahda, said that the cabinet reshuffle had reduced its share of ministers in the government and that it had yielded control of the ministries of justice, interior and foreign affairs, bowing to a central demand of several opposition parties. 2013 8 March- Tunisia’s prime minister announced a new cabinet on Friday, handing over key ministries previously headed by members of the ruling Islamist party to independent figures in an effort to calm the worst political crisis since the country’s revolt more than two years ago. After Revolutions: Libya After violence erupted between Gaddafi and opposition forces in Jan 2011, same time, a multinational coalition launched a large scale airbased military intervention to disable the Gaddafi government's military capabilities and enforce the UN Security Council resolution in March. By the end of March, command of the coalition operations had been assumed by NATO. After Revolutions: Libya In October 2011, Gaddafi and several other leading figures in his government were captured and killed in Gaddafi's hometown of Sirte. On 23 October 2011, the National Transitional Council officially declared that Libya had been liberated. After Revolutions: Libya On 22 November, the NTC named its interim government. On 1 January 2012, the NTC released a 15-page draft law that would regulate the election of a national assembly charged with writing a new constitution and forming a second caretaker government. The proposed law laid out more than 20 classes of people who would be prohibited from standing as candidates in the elections, including Libyans who had ties to Muammar Gaddafi, former officials accused of torturing Libyans or embezzling public funds, active members of the Revolutionary Guard, opposition members who made peace with Gaddafi. After Revolutions: Libya The finalization of the election law would be followed by the appointment of an election commission to divide the country into constituencies and oversee the poll, to be held in June. After Revolutions: Libya On 7 July 2012, Libyans voted in their first parliamentary elections since the end of the dictatorship of Muammar Gaddafi. The election, in which more than 100 political parties have registered, formed an interim 200-member national assembly. This replaced the unelected National Transitional Council, named a prime minister, and formed a committee to draft a constitution. After Revolutions: Libya 2012 August - Transitional government handed power to the General National Congress, which was elected in July. The Congress elects Mohammed Magarief of the liberal National Front Party as its chairman, thereby making him interim head of state. 2012 October -the National Congress elected Ali Zidan, a liberal and leading opposition envoy during the civil war, as the prime minister. The congress is dominated by more liberal-leaning members, but it also has many moderate Islamists and a few Salafists (fundamentalists). After Revolutions: Libya 2012 November - New government led by Ali Zidan is sworn in. 2013 April - The government continues to struggle to impose its authority on militia groups. One military group briefly abducted Prime Minister Zidan's aide Mohamed al-Ghattous on the outskirts of Tripoli.