Course Background

An increasing body of opinion implicates the importance of Physical, cognitive, affective and socio occupational factors in the overall presentation of the patient in front of us.

Essentially, this defines the Biopsychosocial model of illness, one that acknowledges the patient as a ‘whole’ and values the social, cultural and environmental factors that shape an individual’s response to illness: This also fits with a patient centred philosophy of care which places the patient as a partner in their care.

As Physiotherapists practicing within a Biopsychosocial framework we are encouraged to recognize that individuals respond very differently to ‘disease’ in the broadest sense of the term. Individuals may reveal psychosocial risk factors for poor outcome in terms of disability and demonstrate thoughts or behaviours that are simply unhelpful.

Whilst the physiotherapy profession has been urged to move on in their thinking from a biomedical model to a biopsychosocial model, the reality, using chronic low back pain as an example, is that clinicians fall well short (Daykin and Richardson 2004), and would benefit from specific training and mentoring support (Sanders et al 2013). It would seem a sound argument to suggest that CBT provides the fundamental structure with which physiotherapist’s can enhance their clinical practice to bridge the gap in clinical practice by learning a Cognitive Behavioural Approach (CBA).

The British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy defines Cognitive

Behavioural Therapy (CBT) as:

A talking therapy. It has been proved to help treat a wide range of emotional and physical health conditions in adults, young people and children. CBT looks at how we think about a situation and how this affects the way we act. In turn our actions can affect how we think and feel. The therapist and client work together in changing the client’s behaviours, or their thinking patterns, or both of these.

Evidence exists for the use of CBT with a wide range of conditions such as Rheumatoid

Arthritis (NICE guideline 2009), persistent low back pain (NICE guideline 2009) and

Depression in adults with a chronic physical health problems (NICE Guidelines 2009). The

Back Skills Training Trial (lamb et al 2010) demonstrated that non mental health professionals could be trained to deliver a CBA intervention after 2 days training. The study showed that over 1 year, the cognitive behavioral intervention when compared to a one off session of evidence based advice had a sustained effect in terms of pain and disability on troublesome sub-acute and chronic low-back pain at a low cost to the health-care provider.

Implementing psychologically informed management principles into physiotherapy practice presents with many challenges (Foster and Delitto 2011). Physiotherapists after graduating embark upon a steep learning curve that drives a need to learn skills that are perceived to equip the therapist with the ‘tools to treat’. Despite strong arguments supporting psychosocial factors as being the strongest predicators of poor clinical outcome, the majority of continuing professional education reinforces a tissue based biomedical approach. This flourishes within a professional, healthcare and social “culture” that expect physical therapist’s to provide physical treatment. After all the clue for this perception lies in the professional title.

The challenge is integrating psychological management strategies with the evidence based physical therapeutic modalities within undergraduate and post graduate training. Research in the field of low back pain suggests that therapist attitudes and beliefs about low back pain can be modified via training programmes but changing and then maintaining such change in clinical practice is a tougher proposition (Foster and Delitto 2011).

Foster and Delitto (2011) suggest feasible methods of driving change may be to identify opinion leaders within those who have attended training, post course mentoring, establishing peer groups to discuss cases with case study presentations and employerdriven incentives to encourage formal post graduate training and evidence based clinical practice. Such methods may serve to improve the therapist – patient relationship, with a positive effect upon treatment outcomes and be a cost effective use of resources.

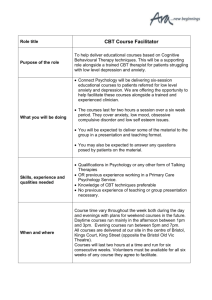

A 2 day training programme in Cognitive Behavioural skills will not equip delegates to provide CBT. To acquire such a skill set takes far more in depth training with a structured supervisory programme as provided via formal higher education facilities in keeping with

BACBP guidelines. The training will however provide basic skill sets to assess and facilitate change to thoughts and behaviours driving viscous cycles detrimental to a person’s physical health. I do not suggest with an evangelical zeal that the skills learnt will be helpful for all patients. As with most skill acquisition, it merely adds to your toolkit with which you can then decide is the most appropriate intervention for individual patients. What I do hope is that the skills may ‘diffuse’ throughout the whole tool kit to underpin a subtle change in clinical practice. The course will stimulate self-reflection and change around current clinical practice that will have a positive impact upon clinical outcomes. The course will also serve to stimulate change within organisation by encouraging peer support networks to facilitate an on-going legacy of professional development in CBT skills.