(Donelson & Nilsen, 2005).

advertisement

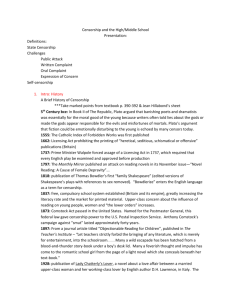

TBA Continuing Education Censorship and Literature for Children and Young Adults The purpose of this review on censorship and book challenges is to revisit our own thoughts about censorship. There are times when this PowerPoint will ask you to stop and reflect about your own experiences and opinions. Warning: You will encounter statements that may challenge your own biases; however, librarians are the sentinels of intellectual freedom, and our professionalism should always win over our personal opinions. Reading assignment: Asheim, Lester. (1953). Not censorship but selection. Wilson Library Bulletin, 28, 63-67. Retrieved March 14, 2008 at the American Library Association Web site: http://www.ala.org/Template.cfm?Section=basics&Templa te=/ContentManagement/ContentDisplay.cfm&ContentI D=109668 “A Censorial Spirit” In the last two decades, objections to books have increased. Parents may object to a title for reasons of “improper” language, stereotypical characters, or that it does not “fit our politically correct time” (Donelson & Nilsen, 2005) What IS a censor? Stop here and think of your own definition… Parents ARE concerned for their children. Many teachers and librarians understand that this is the reason they begin this kind of conversation. They do not necessarily want to come into your library and remove books from the shelves, but they DO need to be heard and respected. Teachers and librarians can listen to the parents, ask questions, and discuss their concerns in hopes of really understanding exactly what the parent’s concern is about. The parent is the only true censor for his or her child’s reading materials. Parents may wonder WHY a particular title is being used in the classroom or on the library shelves—a very valid question. Sometimes the problem can be solved as simply as explaining how a book’s unique characteristics contribute to student learning. Often, there are underlying concerns about certain titles, authors, or even whole series. Political and moral views widely differ in our country, and often the objections arise from point of view. It is important to try to understand their point of view—even if it is different from your own. There are times you may have to help the parent clarify why the book is objectionable. Sometimes parents feel little control over what they see as “protecting” their child. They have no control over what is on TV or playing at local theaters, but they can come to the school to voice objections. Societal fears such as global warming, inflation/recession, sexually transmitted disease, and family problems can make parents vulnerable to political action groups advocating censorship to “restore” American values. The individuals and groups whose mission it is to condemn anything that is not part of their narrow vision of what is right and wrong are censors who will try to control access for everyone . Assumptions about censors and censorship: Any work is potentially censorable by someone, someplace, sometime, for some reason. The newer the work, the most likely it is to come under attack. Censorship is capricious and arbitrary. Censors spread a ripple of fear—schools miles away can feel the effect. Censorship does not come only from those outside the school. (Donelson & Nilsen, 2005) Assumptions about censors and censorship: Libraries without clear, established, board approved policies and procedures for handling censorship are accidents waiting to happen. If one book is removed from a classroom or library, no book is safe any longer. Educators and parents should, ideally, coexist to help each other for the good of the young, but the clash of parents with some educators appears to be sadly inevitable. (Donelson & Nilsen, 2005) Censors… seem unwilling to accept that the more they attack a book, the more it is read do not believe that in protecting the innocents, they expose them to the very thing they abhor often have a simplistic belief that there is a relationship between books and deeds seem to have little faith in the ability of young adults to read and think alternately love and hate librarians and teachers use language carelessly or sloppily (Donelson & Nilsen, 2005) Who are the censors? 1. Those from the right, the conservatives 2. Those from the left, the liberals 3. A group of educators, publishers, and distributors some might assume would be opposed to censorship (Donelson & Nilsen, 2005) Reverend Vincent Strigas: “Some people are saying that we are in violation of First Amendment Rights. I do not think that the First Amendment protects people [who sell] pornographic materials. The Constitution protects only the freedom to do what is right.” (Donelson & Nilsen, 2005) Wrong…. What issues/topics do conservative and liberal censors object to? •“Secular humanism”—any teaching material that denies the existence of or ridicules the worth of absolute values of right or wrong •New Age Movement •Evolution •“Profanity” •Sex education •Drug education (Donelson & Nilsen, 2005) Third type of censors… Teachers, librarians, school officials who themselves censor materials or support others who do. Why? •They fear reprisals. •They do not want to attract attention and want to preserve the “status quo.” •They may regard themselves as highly moral. •They may view classical literature superior to any other literature. (Donelson & Nilsen, 2005) Stop and Think Activity: Intellectual Freedom Do well meaning educators have the right to “censor” materials for children and/or young adults? This could be a teaching partner you work with who does not like the book you are using or a librarian who will not buy Goosebump books. Remember—these are your colleagues—you love and respect them. Who defines right? Who defines wrong? Where are the shades of gray? The third group is mostly defined by fear. “I would not recommend any book any parent might object to.” “The Board of Education knows what parents in our area want their children to read. If teachers don’t feel they can teach what the parents approve, they should move on.” “The teacher is hired by the school board, which represents the public. The public, therefore, has the right to ask any teacher to avoid using any material repugnant to any parent or student.” Sound familiar? (Donelson & Nilsen, 2005) More fear…. “At this level, I don’t feel it’s [censorship] a problem. We don’t deal with controversial material, at least not in English class.” “We have no problems at all in my department. The teachers order books directly and don’t clear them with me or with a committee. But I receive the shipments. Copies of books that I think to be inappropriate simply disappear from my book room.” (Donelson & Nilsen, 2005) Censors cite objections that may sound like these: Offensive because of sex (“filth,” “risqué,” “indecent;” kids would not have sex if it weren’t for these books) This book is an attack on the “American dream” (“un-American,” “procommie”) “peacenik” or “pacifist” Irreligious or against religion Promotes racial harmony or stresses civil rights Offensive language (“profanity”) Drug books—pro or con (kids would not use drugs if it weren’t for these books) Presenting “inappropriate adolescent behavior will cause young people to act inappropriately (Donelson & Nilsen, 2005) What does the law say? Court Decisions… 1st decision attempting to define obscenity, 1868: The Queen v. Hicklin (L.R. 3Q.B. 360): “I think the test of obscenity is this, whether the tendency of the matter charged as depraved and corrupts those whose minds are open to such immoral influences, and into whose hands a publication of this sort may fall” (376) Clear as mud…. (Donelson & Nilsen, 2005) Court Decisions… 1913: United States v. Kennerly (209 F. 119): “I hope it is not improper for me to say that the rule as laid down, however consonant it may be with midVictorian morals, does not seem to me to answer to the understanding and morality of the present time, as conveyed by the words, ‘obscene, lewd, or lascivious.’ I question whether in the end men will regard that as obscene which is honestly relevant to the adequate expression of innocent ideas, and whether they will not believe that truth and beauty are too precious to society at large to be mutilated in the interest of those most likely to pervert them to baser uses” (377). STILL clear as mud…. (Donelson & Nilsen, 2005) Historically, the debate about “obscenity” continued with no clear criteria; however, there cases important to us today. Court decisions about teaching and school libraries: 1969, Tinker v. the Des Moines (Iowa) School District (393 U.S. 503): “First Amendment rights, applied in light of the special characteristics of the school environment, are available to teachers and students. It can hardly be argued that either students or teachers shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate” (381). (Donelson & Nilsen, 2005) Court decisions about teaching and school libraries: Minarcini v. Strongsville (Ohio) City School District (541 F.2d 577): “A library is a storehouse of knowledge. When created for a public school it is an important privilege created by the state for the benefit of the students in the school. That privilege is not subject to being withdrawn by succeeding school boards whose members might desire to ‘winnow’ the library for books the content of which occasioned their displeasure or disapproval. Of course, a copy of a book may wear out. Some books may become obsolete. Shelf space alone may at some point require some selection of books to be retained and books to be disposed of. No such rationale is involved in this case (381-82). (Donelson & Nilsen, 2005) Court decisions about teaching and school libraries: 1978: Right to Read Defense Committee of Chelsea (Massachusetts) v. School Committee of the City of Chelsea (454 F. Supp. 703): “…The Committee claims the absolute right to remove “City” [a poem] from the School Library. It has not such right, and compelling policy considerations argue against any public authority having such an unreviewable power of censorship. There is more at issue here that the poem “City.” If this work may be removed by a committee hostile to its language and theme, then the precedent is set for removal of any other work. The prospect of successive school committee ‘sanitizing’ the school library of view divergent from its own is alarming, whether they do it book by book or one page at a time. What is at state here is the right to read and be exposed to controversial thoughts and language—a valuable right subject to First Amendment protection” (382-83). (Donelson & Nilsen, 2005) Court decisions about teaching and school libraries: 1984, Mozert v. Hawkins County (Tennessee) Public Schools (579 F. Supp. 1051): Parents objected to a Holt, Rinehart, Winston reading series by citing “humanism, secular humanism, Satanism, feminism, evolution, telepathy, internationalism….” The judge ruled in favor of the parents, but the ruling was overturned in the Circuit Court of Appeals. (funded by Beverly LaHaye, leader of the Concerned Women for America) http://www.cwfa.org/articledisplay.asp?id=10 276&department=CWA&categoryid=educati on (Donelson & Nilsen, 2005) A “New” Kind of Censorship… Want to avoid “offensive language?” http://www.randomhouse.com/words/la nguage/avoid_guide.html “The New York sensitivity review guidelines ban ‘language, content, or context that is not accessible to one or more racial or ethnic groups.” Translation: Keep everything bland and down the middle. (390) “This language censorship should be repugnant to those who care about freedom of thought” (Diane Ravitch, 390). (Donelson & Nilsen, 2005) BE prepared…. Librarians should… Have some knowledge about the history of censorship Be up to date with court decisions and titles under attack Read Newsletter on Intellectual Freedom, School Library Journal, English Journal, Journal of Youth Services in Libraries, and Voice of Youth Advocates (Donelson & Nilsen, 2005) Publicize ALA, TLA, and TBA’s policies on book selection Develop a clear plan of action for handling a book challenge Prepare thoughts so that respect and courtesy is maintained while making a reasonable timely response to the parent, librarian, teacher or community member’s concerns Always keep in mind reviews from professional journals using their intended audience guidelines for both reading and interest levels Keep documents recording the reviews, awards, and booklists for each title under consideration When considering books for the Master List remember ... Look at characteristics unique to each book. What is it about that one book that makes it unique? Consider: •Cultural connections •Theme[s] •Language •Author’s style •Characterization/Setting/Conflict •Plot structure •Content (nonfiction) •Topic Having a rationale as to why a book was chosen will help when dealing with censorship issues. What else can we do? Work with the community to gain support for intellectual and academic freedom Discuss intellectual and academic freedom with students Prepare yourself to take on the usual arguments of censors and understand the difference between selection and censorship Be familiar with the organizations and professional associations who will help you (Donelson & Nilsen, 2005) “Selection begins with a presumption in favor of liberty of thought; censorship with a presumption of thought control” (Donelson & Nilsen, 2005). What to do when challenged… Do not panic! Do not be surprised if fellow teachers and librarians do not rush in to give support Ask the concerned parent to discuss the matter with the teacher or librarian first Talk calmly and do not jump to conclusions—this person may only want to be heard Treat this person with courtesy and listen to their comments If necessary, meet with the book challenge committee and follow the procedures outlined in the board policy Resources American Library Association 1. Library Bill of Rights: http://www.ala.org/ala/oif/statementspols/statementsif/librarybillrights.htm 2. Interpretations of the Library Bill of Rights: http://www.ala.org/ala/oif/statementspols/statementsif/interpretations/Default675. htm 3. Code of Ethics: http://www.ala.org/ala/oif/statementspols/codeofethics/codeethics.htm 4. Freedom to Read Statement: http://www.ala.org/ala/oif/statementspols/ftrstatement/freedomreadstatement.htm 5. Libraries: An American Value: http://www.ala.org/ala/oif/statementspols/americanvalue/librariesamerican.htm 6. Online Social Networks: http://www.ala.org/ala/oif/ifissues/onlinesocialnetworks.htm 7. Notable First Amendment Court Cases: http://www.ala.org/ala/oif/firstamendment/courtcases/courtcases.htm 8. Intellectual Freedom and Censorship Questions and Answers: http://www.ala.org/ala/oif/basics/intellectual.htm 9. Office of Intellectual Freefdom: http://www.ala.org/ala/oif/aboutoif/aboutofficeintellectual.htm 10. First Amendment: http://www.ala.org/ala/oif/firstamendment/firstamendment.htm Resources Texas Library Association. (1996). Intellectual freedom handbook. Retrieved March 14, 2008 from the Texas Library Association’s Web site at http://www.txla.org/pubs/ifhbk.html Ramsey, Inez. (1999) Intellectual freedom. Retrieved March 14, 2008 at the Internet School Library Media Center Web site at: http://falcon.jmu.edu/~ramseyil/free.htm International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions. (2007). Intellectual freedom statements. Retrieved March 14, 2008 at the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions Web site at: http://www.ifla.org/faife/ifstat/ifstat.htm Vandergrift, Kay. (2008). Censorship, the internet, intellectual freedom, and youth. Retrieved March 14, 2008 at Rutgers Web site at: http://www.scils.rutgers.edu/~kvander/censorship.html References Asheim, Lester. (1953). Not censorship but selection. Wilson Library Bulletin, 28, 63-67. Donelson, Kenneth and Nilsen, Aileen. (2005). Literature for today’s young adults. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon. Happy reading!