a presentation for the 2005 ASIS&T

advertisement

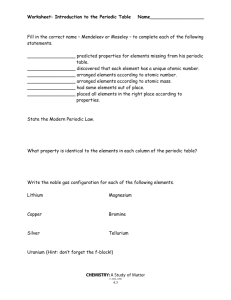

Linnaeus, Mendeleev, Dewey, and Ranganathan: What can they tell us about the organization of information today? Purpose • • • To gain insights about the creation of universal languages of discourse. To understand better the intellectual capital invested in legacy conceptual systems. To relate these insights to our current challenges in organizing information in the digital age. Classification and namegiving “The first step in wisdom is to know the things themselves; this notion consists in having a true idea of the objects; objects are distinguished and known by classifying them methodically and giving them appropriate names. Therefore, classification and namegiving will be the foundation of our science.” Linnaeus, Carolus (1964). Systema Naturae, 1735. Facsimile of the first edition, with an introduction and a first English translation of the "Observationes" by M. S. J. Engle-Ledeboer and H. Engel. Nieuwkoop: De Graaf. Before Linnaeus Ancients • • Theophrastus (ca.370–ca.286 B.C.) - categorized plants into trees, shrubs, undershrubs, herbs. Dioscorides (first century A.D.) – categorized plants according to their medical and therapeutic properties and uses. 16th Century • • • • Otto Brunfels (1464–1534), Leonhard Fuchs (1501–1566) – herbalists who tried to describe and illustrate all known plants. Andrea Caesalpino (1519–1603) began to focus on organizing plants by fruits and seeds, including superior and inferior ovaries and the number of locules in an ovary. Johann Bauhin (1541–1631) treated about 5,000 plants and their synonymies with good diagnoses in his illustrated Historia Plantarum Universalis. Caspar Bauhin (1560–1624) produced a Pinax, containing names and synonyms of 6,000 species, and pioneered the use of binomial nomenclature. 17th century • • Joseph Pitton de Tournefort (1656–1708) used a form classification that divided plants into groups based on petal characters. John Ray (1628–1705) classified some 18,000 species in his Methodus Plantarum, using a system based on form and gross morphology of plant structures. Source: Order from Chaos: Linnaeus Disposes http://huntbot.andrew.cmu.edu/HIBD/Exhibitions/OrderFromChaos/pages/02Linnaeus/search.shtml 18th Century Europe • • • • Lavished attention on natural history Fashionable to own collections of stuffed birds, pressed flowers, preserved butterflies, seashells, etc. European powers engaged in worldwide and local expeditions to identify natural products that are of economic importance. Europeans encountered thousands of species of plants, animals, and rocks/minerals each year. Early graphic representations of the relationships between living organisms. Source: Withgott, J. Is it “So long, Linnaeus?” BioScience, 50(8): 646-651. Binomial Nomenclature & Linnean Taxonomy • • • • • • • Generic (one-word) and specific name (two-word) In Latin First letter of generic in upper-case; specific name all in lower-case (e.g. Homo sapiens) Genus name shortened to the first letter in subsequent mention of the name but never omitted (e.g. H. sapiens) Genus and species names always italicized; names of higher taxa are not. Authorship of names Trinomials for subspecies http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Binomial_nomencl ature Human (Homo sapiens) • Kingdom Animalia • Phylum Chordata • Subphylum Vertebrata • Class Mammalia • Subclass Eutheria • Order Primates • Suborder Haplorhini • Family Hominidae • Genus Homo • Species sapiens Uniform Description See full explanation at: Order from Chaos: Linnaeus Disposes. The Linnean System in Action. http://huntbot.andrew.cmu.e du/HIBD/Exhibitions/OrderFr omChaos/pages/02Linnaeus /system.shtml Carl Linnaeus • • • • • • Born May 23, 1707 in Rashult, Sweden. Died January 10, 1778 in Uppsala, Sweden. His father, a clergyman, maintained an impressive garden. Gave the young Linnaeus his own small garden to tend. “His toys were flowers.” (Caddy, 1887) Linnaeus’ Latin motto: Tantus amor Florum! (such a great love of flowers’) A doctor of medicine. Blunt, W. (2001). Linnaeus: the compleat naturalist. London: Princeton University Press. Caddy, F. (1887). Through the fields with Linnaeus; a chapter in Swedish history. Boston: Little, Brown, and Co. Linnaeus’ Lapland Journey • • • May to October 1732, covered 3,000 miles. 25 years of age. Work based on these travels: Flora Lapponica Linnaea borealis (twinflower) Source: http://www.forestryimages.org/images/768x512/0807053.jpg Sexual Parts of a Flower “Anthers are the male genital organs; when they strew their genital flour (pollen) on the stigma, the female genital organ, fertilization takes place.” (Linnaeus, Systema Naturae) Image sources: (left) www.linnaeus.uu.se/ online/lvd/2_1.html (right) http://images.encarta.msn.com Graphs and tables in Systema Naturae Observation and the naked eye “I predict, that botanists surely will say, that my method presents too great a difficulty notably for examining the very small parts of a flower, which one can hardly see with the naked eye. I reply: if everybody interested would have a microscopium (magnifying glass!), a most necessary instrument, at hand, what work would there be left? I myself, however, have examined all these plants with the naked eye, and without any use of a microscopium.” Linnaeus, Carolus (1964). Systema Naturae, 1735. Facsimile of the first edition, with an introduction and a first English translation of the "Observationes" by M. S. J. Engle-Ledeboer and H. Engel. Nieuwkoop: De Graaf. Questions for us • • • • What are the objects of our observation as information professionals? Taking into consideration our tools for observation (cameras, videorecorders, audiorecorders, etc.), how do we characterize observation in the digital age? To what extent are our senses involved? What sensual impressions does the world have on us? Linnaeus and the theory of evolution • • • Linnaeus’ nested hierarchy of groups within groups fit well with many people’s conceptions of nature. (Before 1859, often explained as divine design.) The Linnean hierarchical pattern was compatible with the Darwinian genealogical tree. So, although evolution explained the hierarchical (tree-like) pattern of life’s history, taxonomists felt no need to change how they reflected the pattern and the Linnean framework was retained. Phylogenetic systematics – replacing Linnean hierarchical pattern based on ranks with cladograms and phylogenetic trees showing relationships among organisms based on recency of divergence. Source: Withgott, J. Is it “So long, Linnaeus?” BioScience, 50(8): 646-651. The Periodic Table of Elements Source: http://chemlab.pc.maricopa.edu/periodic/periodic.html Before Mendeleev • • • • • • • • • • • • Ancient Greeks – four elements: earth, air, fire, water. Alchemy – the idea of transforming one metal into another, especially into gold. (Ancient Egyptians well into the 17th century) Early efforts at classifying the elements in the 18th century run parallel with the classification of minerals. 1789 – the law of conservation of matter (Lavoisier) 1806 – the law of definite proportions (Proust) 1808 – the law of multiple proportions (Dalton) 1808 – the law of combining volumes of gases (Gay-Lussac) 1808 – Dalton’s atomic theory 1811- Avogadro’s hypothesis 1817 – Dobereiner’s triads 1864 – Newlands’ law of octaves 1868 – Meyer’s periodic table (published in 1870) Sources: Morris, R. (2003). The Last Sorcerers: the path from alchemy to the periodic table. Washington, D.C: Joseph Henry Press. Van Spronsen, J. W. (1969). The Periodic System of Chemical Elements: A history of the first hundred years. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Publishing Co. Dmitri Mendeleev • • • Born February 7, 1834 in Tobolsk, Siberia. Died February 2, 1907 in St. Petersburg, Russia. Professor of chemistry, St. Petersburg University Gordin, M. (2004). A well-ordered thing: Dmitrii Mendeleev and the shadow of the periodic table. New York: Basic Books. Mendeleev’s early drafts and his 1869 periodic table (Left) A draft of Mendeleev’s periodic system dated 17 Feb 1869. (Right) The first published form of Mendeleev’s periodic system. Notice the gaps with question marks for elements that Mendeleev suspected existed. One has to rotate the table by 90 degrees clockwise to see the resemblance to the horizontal rows and vertical columns that we are familiar with today. (Source: Gordin, M. (2004). A wellordered thing: Dmitrii Mendeleev and the shadow of the periodic table. New York: Basic Books..Red circling mine.) Mendeleev’s 1871 table Source: http://chemlab.pc.maricopa.edu/periodic/foldedtable.html Examples of the hundreds of ways used to represent the periodic law of the elements. (Left) Spiral similar to a triple lemniscate by Charles Janet, 1928. (Right) Helix with four sizes of revolutions on four separate axes by Paul Giguere, 1966. (Source: Mazurs, E. G. (1974). Graphic Representations of the Periodic System During One Hundred Years. Alabama: The University of Alabama Press.) See also http://chemlab.pc.maricopa.edu/periodic/styles.html Statement of the Periodic Law “The properties of the elements as well as the forms and properties of their compounds are in a periodic dependence or, expressing ourselves algebraically, form a periodic function of the atomic weight of the elements” [p. 16. Mendeleev, D. (1891). Principles of Chemistry, Vol. 2. Trans. George Kamensky. London: Longmans, Green.] The periodic table and subatomic particles. “It is of interest to note that the periodic table reached its final forms before atomic structure revealed the basis for periodicity. The discovery of sub-atomic particles in no way threw the system of classification into doubt but reinforced the general decisions which had been made. It was only at the end of the table that the study of electronic configuration and the creation of transuranium elements brought about a change of arrangement from transition elements to rare earth analogues.” - Aaron J. Ihde, in his foreword to Van Spronsen, J. W. (1969). The Periodic System of Chemical Elements: A history of the first hundred years. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Publishing Co. Usefulness of Mendeleev’s system Mendeleev stated that the usefulness of a system increases with the number of its applications. His periodic table can be used in the following ways: 1. As a classification of elements; 2. To determine the atomic weights of elements not sufficiently analyzed; 3. To examine properties of unknown compounds; 4. To correct erroneously determined atomic weights; and 5. To collect information about the properties of compounds. Questions for us • • What property or properties of information can we use to organize information objects that will reveal gaps about our knowledge of a specific domain and which can lead us to discoveries or novel ideas? Do information organizers have to be experts in a specific knowledge domain to be able to do this? Mendeleev was a chemist but we still wonder whether the process he went through to observe the repetitions of properties after a number of elements could have been observed by somebody with a basic knowledge of chemistry. Would that person have known what to look for and be alert for possible patterns? Before Dewey The problem of the multitude of books 1255- Vincent de Beauvais wrote “Since the multitude of books, the shortness of time and the slipperiness of memory do not allow all things which are written to be equally retained in the mind, I decided to reduce in one volume in a compendium and in summary order some flowers selected according to my talents from all the authors I was able to read.” 1545 - “In the preface to his massive project of cataloguing all known books in the Bibliotheca univeralis, Conrad Gesner complained of that ‘confusing and harmful abundance of books,’ a problem which he called on kings and princes and the learned to solve.” 1680 – Leibniz spoke of that “horrible mass of books which keeps on growing” 1685 – Adrien Baillet warned, “We have reason to fear that the multitude of books which grows every day in a prodigious fashion will make the following centuries fall into a state as barbarous as that of the centuries that followed the fall of the Roman Empire. Unless we try to prevent this danger by separating those books which we must throw out or leave in oblivion from those which one should save and within the latter between what is useful and what is not.” 1704 – Jonathan Swift lamented and parodied what he called ‘Index learning,’ referring to the growth of epitomes,abridgements,and alphabetical indexes. These, he said,were advertised as ‘methods’ for not reading the whole book..” Source: Blair, A. (2003). Reading strategies for coping with information load ca 1550-1700. Journal of the History of Ideas. 64(1): 11-28. Yeo, R. (2003). A solution to the multitude of books: Ephraim Chambers’ Cyclopaedia (1728) as “the best book in the universe.” Journal of the History of Ideas. 64(1): 61-72. Before Dewey (part 2) Modern Bibliographic Systems 1841 – Panizzi’s rules for the compilation of the catalog of printed books in the British Museum’s Department of Printed Books (now British Library). 1848 – Panizzi makes the case for an alphabetic catalogue for the British Library. 1853 – Charles Jewett’s 33 rules for the construction of catalogs of libraries. 1876 – Charles Ammi Cutter’s rules for a dictionary catalog. Melvil Dewey • • • • Born December 10, 1851 in Adams Center, New York. Died December 26, 1931 in Lake Placid, New York. Attended Amherst College from 18701874. Organized conference that would establish the ALA Wiegand, W. (1996). The Irrepressible reformer: a biography of Melvil Dewey. Chicago: American Library Association. Dewey on theory and practice Dewey (1876) acknowledges that “theoretically, the division of every subject into just nine heads is absurd.” “philosophical theory and accuracy have been made to yield to practical usefulness. The impossibility of making a satisfactory classification of all knowledge as preserved in books, has been appreciated from the first, and nothing of the kind attempted. Theoretical harmony and exactness has been repeatedly sacrificed to the practical requirements of the library or to the convenience of the department in the college.” Dewey, M. (1876). A classification and subject index for cataloguing and arranging the books and pamphlets of a library. Facsimile reprinted by Forest Press Division, Lake Placid Educational Foundation. Retrieved 2/12/05 from Project Gutenberg http://www.gutenberg.org/dirs/1/2/5/1/12513/12513-h/12513-h.htm. Texts that have influenced Dewey • • • • Edward Edwards’ “Memoirs of Libraries.” Charles C Jewett’s “A Plan for Stereotyping Titles.” William Torrey Harris’ article on book classification which appeared in the Journal of Speculative Philosophy. Nathaniel Shurtleff’s pamphlet entitled “A Decimal System for the Arrangement and Administration of Libraries” privately printed in 1856. Dewey Decimal Classification 10 Main Classes • 000 Computers, information and general reference • 100 Philosophy and psychology • 200 Religion • 300 Social sciences • 400 Language • 500 Science and mathematics • 600 Technology • 700 Arts and recreation • 800 Literature • 900 History and geography Notational Hierarchy 796 Athletic and outdoor sports and games 796.3 Ball games 796.34 Racket games 796.342 Tennis (Lawn tennis) 796.343 Squash 796.345 Badminton 796.346 Table tennis 796.347 Lacrosse Structural Hierarchy 972 Middle America Mexico 636.2 Ruminants and Camelidae Bovidae Cattle Source: Mitchell, J. (2001) Relationships in the Dewey Decimal Classification System. In C. Bean & R. Green (2001). Relationships in the Organization of Knowledge. Dordrecht, Germany: Kluwer Academic Publishers. Relationships in DDC Generic 583-584 Angiospermae (Flowering plants) 583 Magnoliopsida (Dicotyledons) 583.3 Ranunculidae 583.34 Ranunculales (Ranales) 583.35 Papaverales (Rhoedales) 583.36 Sarraceniales Whole-part 611.31 Mouth 611.313 Tongue 611.314 Teeth 611.315 Palate 611.316 Salivary glands 611.317 Lips 611.318 Cheeks Instance 005.133 Specific programming languages Arrange alphabetically by name of programming language, e.g. C++ Polyhierarchical 551.21 Volcanoes Class here comprehensive works on craters For meteorite craters, see 551.397 Equivalence 572.86 DNA (Deoxyribonucleic acid) Associative 004.7 Periphals See also 004.64 for communication devices. Source: Mitchell, J. (2001) Relationships in the Dewey Decimal Classification System. In C. Bean & R. Green (2001). Relationships in the Organization of Knowledge. Dordrecht, Germany: Kluwer Academic Publishers. Relative Index & Tables for synthesis of numbers Relative Index – alphabetical list of subjects Sample entry: Mercury (Element) Mercury (Planet) 669.71 523.41 Tables Table 1: Standard subdivisions (form, time) Table 2: Geographic areas and persons Table 3: Subdivisions for individual literatures, for specific literary forms. Table 4: Subdivisions of individual languages Table 5: Ethnic groups Dewey’s Four Causes • • • • Metric reform Spelling reform Shorthand Libraries Dewey to Ranganathan (13 Nov. 1930) “Naturali the sistem ist publisht in 1876 was from the standpoint of our American libraries. Thru the 12 editions, it has constantli broadened. But we need speciali to cover Asia mor adequateli and hope we shall hav yur aktiv cooperation in making the decimal sistem stil mor wydli useful.” (p. 30, Ranganathan, S. R. (1967). Prolegomena to library classification. Bombay: Asia Pub. House. ) Questions for us • • • In what information contexts can we impose hierarchical structures today? How can we make hierarchical knowledge structures more flexible in linking to other knowledge structures between different domains? How can we use it to define shared rules of inference and shared vocabularies across domains? Bibliographic Classification Schemes after Dewey • • • • • • Expansive Classification (Charles Ammi Cutter, 1890s) Universal Decimal Classification (Paul Otlet, Henri La Fontaine, 1895-) Library of Congress Classification Subject Classification (James Duff Brown, 1906-) Colon Classification (S.R. Ranganathan, 1933-) Bibliographic Classification (Henry Evelyn Bliss, 1940-) Shiyali Ramamrita Ranganathan • • • • Born August 9, 1892 in Madras, India. Died September 27, 1972 in Bangalore, India. Taught mathematics and physics First librarian of the University of Madras Ranganathan’s inspiration “I could not then say that what was needed was a faceted classification. But something was engaging my thought continuously. While in that condition, I happened to see a Meccano set in one of the Selfridges Stores in London. That gave me the clue. It made me feel that the class number of a subject should really be got by assembling ‘Facet Numbers’ found in several distinctive schedules, even as a toy is made by assembling an assortment of parts.” - (p. 106, Ranganathan, S. R. (1967). Prolegomena to library classification. Bombay: Asia Pub. House.) Facets Facets – “a generic term used to denote any component – be it a basic subject or an isolate – of a Compound Subject, and also its respective ranked forms, terms, and numbers” (Ranganathan, 1967, p. 88). Five Laws of Library Science • • • • • Books are for use Every reader his book Every book its reader Save the time of the reader (and its corollary – Save the time of the staff) Library is a growing organism. Five Fundamental Categories • • • • • Time – “in accordance with what we commonly understand by that term.” Millenium, century, decade, year, and so on are its manifestations. Space – as with time, in accordance with its usual significance. “The surface of the earth, the space inside it, and the space outside it” are manifestations of space. Energy – ‘its manifestation is action of one kind or another. The action may be among and by all kinds of entities – inanimate, animate, conceptual, intellectual, and intuitive.” Matter – its manifestations are of two kinds – Material, which is what an entity is made of, e.g. steel, timber, or Property, e.g. being 2 feet wide and 8 ft long. Both are intrinsic to the entity but are not the entity itself. Personality – Ranganathan regarded this category as the most difficult to identify. “It is too elusive. It is ineffable.” The process of identifying it is a Method of Residues – “if a certain manifestation is easily determined not to be one of Time, Space, Energy, or Matter, it is taken to be the manifestation of the fundamental category, Personality Hierarchy in Ranganathan’s System Ranganathan’s diagram to illustrate his theory of classification. Shows Original Universe, Division, Assortment, Classes, Arrays, Collateral Classes, illustrative Pseudo-classes, Chains, Subordinate classes, Order of classes and of arrays. The numbers in the rectangles are decimal fractions. [p. 46 Ranganathan, S. R. (1967). Prolegomena to library classification. Bombay: Asia Pub. House.] Colon Classification (main classes) z Generalia 1 Universe of Knowledge 2 Library Science 3 Book Science 4 Journalism A Natural Sciences ß Mathematical Sciences B Mathematics Г Physical Sciences C Physics D Engineering E Chemistry F Technology G Biology H Geology HZ Mining I Botany J Agriculture K Zoology KZ Animal Husbandry L Medicine LZ Pharmacognosy M Useful Arts Δ Spiritual Experience and Mysticism Μ Humanities and Social Sciences v Humanities N Fine Arts NZ Literature and language O Literature P Linguistics Q Religion R Philosophy S Psychology Σ Social Sciences T Education U Geography V History W Political Science X Economics Y Sociology YZ Social Work Z Law Summary • • • • • Knowledge domains went through a factgathering period. Facts reached critical mass. Terminology for describing them increased and became confusing. Lists, catalogs, encyclopedias, glossaries, indexes, and other compilations were created to manage the growing body of information. The plethora of finding aids themselves became confusing. Questions for us • • • • What is different in the digital age? Can we look at an object from different perspectives and still be able to relate things together? What combinations of hierarchical and faceted organization of information can we put together to meet our current information needs? What other knowledge structures can we create for digital information Semantic Web – Enabling Technologies and Standards Layer Cake Sources: (left figure) Berners-Lee, T. & Hendler, J. Publishing on the semantic web – the coming Internet revolution will profoundly affect scientific information. Nature, 410 (6832): 1023-1024 APR 26 2001. (right figure) http://www.w3.org/2002/Talks/04-sweb/slide12-0.html Bibliography (Linnaeus) 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. Blunt, W. (2001). Linnaeus: the compleat naturalist. London: Princeton University Press. Bock, W. (2004). Species: the concept, category, and taxon. Journal of Zoological Systematics & Evolutionary Research, 42(): 178-190. Farber, P. (2000). Finding order in nature: the naturalist tradition from Linnaeus to E.O. Wilson. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press. Larson, J. (1971). Reason and experience: the representation of natural order in the work of Carl von Linné. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. Linnaeus, Carolus (1964). Systema Naturae, 1735. Facsimile of the first edition, with an introduction and a first English translation of the "Observationes" by M. S. J. Engle-Ledeboer and H. Engel. Nieuwkoop: De Graaf. Stearn, W. (2001). Appendix: Linnean Classification, Nomenclature, and Method. In W. Blunt. Linnaeus: the compleat naturalist. London: Princeton University Press. Tournefort, Joseph Pitton de. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved January 29, 2005, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online. <http://www.search.eb.com.offcampus.lib.washington.edu/eb/article?tocId=9073064 Withgott, J. Is it “So long, Linnaeus?” BioScience, 50(8): 646-651. Bibliography (Mendeleev) 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. Bensaude-Vincent, B. (2001). Graphic representations of the periodic system of chemical elements. In U. Klein (ed.). Tools and Modes of Representation in the Laboratory Sciences. Dordrecht, Germany: Kluwer Academic Publishers. Gordin, M. (2004). A well-ordered thing: Dmitrii Mendeleev and the shadow of the periodic table. New York: Basic Books. Klein, U. (Ed.) (2001). Tools and Modes of Representation in the Laboratory Sciences. Dordrecht, Germany: Kluwer Academic Publishers. Mazurs, E. G. (1957). Types of Graphic Representation of the Periodic System of Chemical Elements. La Grange, Ill.: E. Mazurs. Mazurs, E. G. (1974). Graphic Representations of the Periodic System During One Hundred Years. Alabama: The University of Alabama Press. Mendeleev, D. (1869). On the Relationship of the Properties of the Elements to their Atomic Weights, Zhurnal Russkoe Fiziko-Khimicheskoe Obshchestvo 1, 60-77; abstracted in Zeitschrift für Chemie 12, 405-406 (1869); abstract translated and annotated in http://web.lemoyne.edu/~giunta/EA/MENDELEEVann.HTML Mendeleev, D. (1879). The periodic law of the chemical elements. Chemical News, 40(): 243. Mendeleev, D. (1891). Principles of Chemistry, Vol. 2. Trans. George Kamensky. London: Longmans, Green. Morris, R. (2003). The Last Sorcerers: the path from alchemy to the periodic table. Washington, D.C: Joseph Henry Press. Scerri, E. (2001). The Periodic Table: the ultimate paper tool in chemistry. In U. Klein (ed.). Tools and Modes of Representation in the Laboratory Sciences. Dordrecht, Germany: Kluwer Academic Publishers. Van Spronsen, J. W. (1969). The Periodic System of Chemical Elements: A history of the first hundred years. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Publishing Co. Bibliography (Dewey) 1. Chan, L. (1994). Cataloging and Classification: An Introduction. New York: McGraw-Hill. 2. Dewey, M. (1876). A classification and subject index for cataloguing and arranging the books and pamphlets of a library. Facsimile reprinted by Forest Press Division, Lake 3. 4. Placid Educational Foundation. Retrieved 2/12/05 from Project Gutenberg http://www.gutenberg.org/dirs/1/2/5/1/12513/12513-h/12513-h.htm. Mitchell, J. (2001) Relationships in the Dewey Decimal Classification System. In C. Bean & R. Green (2001). Relationships in the Organization of Knowledge. Dordrecht, Germany: Kluwer Academic Publishers. Wiegand, W. (1996). The Irrepressible reformer: a biography of Melvil Dewey. Chicago: American Library Association. Bibliography (Ranganathan) 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. Garfield, E (1984). A Tribute to S. R. Ranganathan, the Father of Indican Library Science. Part 1. Life and Works. In Essays of an Information Scientist 7 (1984): 37-44. [Also available at http://www.garfield.library.upenn.edu/essays/v7p045y1984.pdf] Kwasnik, B. (1992). The legacy of facet analysis. In R.N. Sharma (Ed). S.R. Ranganathan and the West (pp. 98-111). New Delhi, India: Sterling. La Barre, K. (2004). The art and science of classification: Phyllis Allen Richmond, 1921-1997. Library Trends, 52(4): 765-791. Mills, J. (2004). Faceted classification and logical division in information retrieval. Library Trends, 52(3): 541-570. Prieto-Diaz, R. (1991). Implementing faceted classification for software re-use. Communications of the ACM. 34(5): 88-97. Ranganathan, S. R. (1967). Prolegomena to library classification. Bombay: Asia Pub. House. Ranganathan, S. R. (1965). The Colon classification. New Bruswick, N.J., Graduate School of Library Service, Rutgers, the State University. Ranganathan, S.R. (1962). Elements of library classification. Bombay: Asia Publishing House. Star, S. (1998). Grounded Classifications: Grounded Theory and Faceted Classifications. Library Trends 47: 218-252. Svenonius, E. (1992). Ranganathan and classification science. Libri. 42(3): 176-183. Wilson, P. (1968). Two kinds of power: an essay on bibliographical control. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. Bibliography (General) Blair, A. (2003). Reading strategies for coping with information load ca 1550-1700. Journal of the History of Ideas. 64(1): 11-28. Ogilvie, B. W. (2003). The many books of nature: Renaissance naturalists and information overload. Journal of the History of Ideas. 64(1): 29-40. Yeo, R. (2003). A solution to the multitude of books: Ephraim Chambers’ Cyclopaedia (1728) as “the best book in the universe.” Journal of the History of Ideas. 64(1):61-72. Trivia Section Heels, Hair and other trivia on the life of Linnaeus, Mendeleev, Dewey, and Ranganathan. Linnaeus on High Heels “Nature had not given high heels to man and Nature knew best, for the wearers of these bushkins could run as nimbly as if they went barefoot.” - Quoted in [Blunt, W. (2001). Linnaeus: the compleat naturalist. London: Princeton University Press. p. 44, a comment on the Lapps’ half-boots called ‘kangor’ which were cheap, comfortable, waterproof, and have no heels.] Mendeleev’s Hair (as told in Morris, R. (2003). The Last Sorcerers: the path from alchemy to the periodic table. Washington, D.C: Joseph Henry Press. p. 157-158.) In 1884 the Scottish chemist Sir William Ramsay went to London to attend a dinner honoring William Perkin, the discoverer of mauve, the first synthetic dye. Arriving early, he encountered “a peculiar foreigner, every hair of whose head acted in independence of every other.” When the foreigner approached, bowing, Ramsay said, “We are to have a good attendance, I think?” Discovering that the man didn’t speak English, Ramsay asked him if he spoke German. “Ja, ein wenig,” the foreigner replied. “Ich bin Mendeleev.” Ramsay related later that, “He is a nice sort of fellow, but his German is not perfect. He said he was raised in East Siberia and knew no Russian until he was seventeen years old. I suppose he is a Kalmuck or one of those outlandish creatures.” Dmitri Mendeleev wasn’t a Kalmuck (Budhisht Mongols), but he did have something of an outlandish appearance. He dressed reasonably well, but his unkempt white hair fell to his shoulders. He was in the habit of having his hair and beard cut once a year, and to some he might have looked like a Siberian shaman than a distinguished chemist. [In the same book cited above, see also the story of how Mendeleev’s mother, Maria, determined to get the best education for her son, took the then 15-yr old Dmitri on a 1,300-mile hitchhike to Moscow.] Dewey DUI Dewey was named Melville Louis Kossuth Dewey. He never used his middle names. He shortened his first name to Melvil and for a while spelled his last name as “Dui.” What Ranganathan did on his wedding day. “During his 20 years of service as librarian of the University of Madras, he took no leave. He worked even on his wedding day, returning to the library shortly after the ceremony.” - Garfield, 1984. * Ranganathan did establish the Sarada Ranganathan Endowment for Library Science in honor of his wife.