Managerial Economics & Business

Strategy

Chapter 4

The Theory of

Individual Behavior

McGraw-Hill/Irwin

Copyright © 2010 by the McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved.

Overview

I. Consumer Behavior

– Indifference Curve Analysis.

– Consumer Preference Ordering.

II. Constraints

– The Budget Constraint.

– Changes in Income.

– Changes in Prices.

III. Consumer Equilibrium

IV. Indifference Curve Analysis & Demand

Curves

– Individual Demand.

– Market Demand.

4-2

Consumer Behavior

Consumer Opportunities

– The possible goods and services consumer can

afford to consume.

Consumer Preferences

– The goods and services consumers actually

consume.

4-3

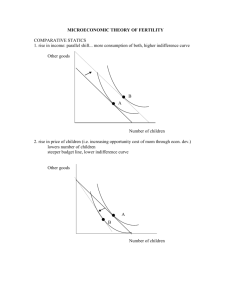

Indifference Curve Analysis

Indifference Curve

– A curve that defines the

combinations of 2 or more

goods that give a consumer

the same level of satisfaction.

Good Y

III.

II.

I.

Marginal Rate of

Substitution

– The rate at which a consumer

is willing to substitute one

good for another and maintain

the same satisfaction level.

Good X

4-4

Consumer Preference Ordering

Properties

Completeness

More is Better

Diminishing Marginal Rate of Substitution

Transitivity

4-5

Complete Preferences

Completeness Property

– Consumer is capable of

expressing preferences (or

indifference) between all

possible bundles. (“I don’t know”

is NOT an option!)

• If the only bundles available

to a consumer are A, B, and

C, then the consumer

is indifferent between A

and C (they are on the

same indifference curve).

will prefer B to A.

will prefer B to C.

Good Y

III.

II.

I.

A

B

C

Good X

4-6

More Is Better!

More Is Better Property

– Bundles that have at least as

much of every good and more of

some good are preferred to other

bundles.

• Bundle B is preferred to A

since B contains at least as

much of good Y and strictly

more of good X.

• Bundle B is also preferred to

C since B contains at least as

much of good X and strictly

more of good Y.

• More generally, all bundles on

ICIII are preferred to bundles

on ICII or ICI. And all bundles

on ICII are preferred to ICI.

Good Y

III.

II.

I.

100

A

B

C

33.33

1

3

Good X

4-7

Diminishing MRS

MRS

– The amount of good Y the consumer

is willing to give up to maintain the

same satisfaction level decreases as

more of good X is acquired.

– The rate at which a consumer is willing

to substitute one good for another and

maintain the same satisfaction level.

Good Y

To go from consumption bundle A

to B the consumer must give up

50 units of Y to get one additional 100

unit of X.

To go from consumption bundle B

50

to C the consumer must give up

16.67 units of Y to get one

33.33

additional unit of X.

25

To go from consumption bundle C

to D the consumer must give up

only 8.33 units of Y to get one

additional unit of X.

III.

II.

I.

A

B

C

1

2

3

D

4

Good X

4-8

Consistent Bundle Orderings

Transitivity Property

Good Y

– For the three bundles A, B,

and C, the transitivity property

implies that if C B and B A,

then C A.

– Transitive preferences along

100

with the more-is-better

property imply that

75

• indifference curves will not

50

intersect.

• the consumer will not get

caught in a perpetual cycle

of indecision.

III.

II.

I.

A

C

B

1

2

5

7 Good X

4-9

The Budget Constraint

Opportunity Set

– The set of consumption bundles

that are affordable.

• PxX + PyY M.

Budget Line

Y

The Opportunity Set

Budget Line

M/PY

Y = M/PY – (PX/PY)X

– The bundles of goods that exhaust

a consumers income.

• PxX + PyY = M.

Market Rate of

Substitution

– The slope of the budget line

• -Px / Py.

M/PX

X

4-10

Changes in the Budget Line

Changes in Income

– Increases lead to a

parallel, outward shift in

the budget line (M1 > M0).

– Decreases lead to a

parallel, downward shift

(M2 < M0).

Changes in Price

– A decreases in the price of

good X rotates the budget

line counter-clockwise (PX0

> PX1).

– An increases rotates the

budget line clockwise (not

shown).

Y

M1/PY

M0/PY

M2/PY

Y

M0/PY

M2/PX

M0/PX

M1/PX

X

New Budget Line for

a price decrease.

M0/PX0

M0/PX1

X

4-11

Consumer Equilibrium

The equilibrium

consumption bundle

is the affordable

bundle that yields

the highest level of

satisfaction.

– Consumer equilibrium

occurs at a point where

MRS = PX / PY.

– Equivalently, the slope of

the indifference curve

equals the budget line.

Y

M/PY

Consumer

Equilibrium

III.

II.

I.

M/PX

X

4-12

Price Changes and Consumer

Equilibrium

Substitute Goods

– An increase (decrease) in the price of good X leads to

an increase (decrease) in the consumption of good Y.

• Examples:

Coke and Pepsi.

Verizon Wireless or AT&T.

Complementary Goods

– An increase (decrease) in the price of good X leads to

a decrease (increase) in the consumption of good Y.

• Examples:

DVD and DVD players.

Computer CPUs and monitors.

4-13

One Extreme Case: Perfect Substitutes

Perfect substitutes: two goods with straightline indifference curves,

constant MRS

Example: nickels & dimes

Consumer is always willing to trade

two nickels for one dime.

4-14

Complementary Goods

When the price of

Pretzels (Y)

good X falls and the

consumption of Y

rises, then X and Y M/PY

1

are complementary

goods. (PX1 > PX2)

B

Y2

II

A

Y1

I

0

X1 M/PX1

X2

M/PX2

Beer (X)

4-15

Another Extreme Case: Perfect Complements

Perfect complements: two goods with right-angle

indifference curves

Example: left shoes, right shoes

{7 left shoes, 5 right shoes}

is just as good as

{5 left shoes, 5 right shoes}

4-16

Optimization: What the Consumer Chooses

The optimal bundle is at the point

where the budget constraint touches

the highest indifference curve.

MRS = relative price

at the optimum:

The indiff curve and

budget constraint

have the same slope.

4-17

Income Changes and Consumer

Equilibrium

Normal Goods

– Good X is a normal good if an increase

(decrease) in income leads to an increase

(decrease) in its consumption.

Inferior Goods

– Good X is an inferior good if an increase

(decrease) in income leads to a decrease

(increase) in its consumption.

4-18

Normal Goods

An increase in

income increases

the consumption of

normal goods.

Y

M1/Y

(M0 < M1).

B

Y1

M0/Y

II

A

Y0

I

0

X0 M0/X

X1

M1/X

X

4-19

Decomposing the Income and

Substitution Effects

Initially, bundle A is consumed. A

decrease in the price of good X

expands the consumer’s opportunity

set.

Y

C

The substitution effect (SE) causes the

consumer to move from bundle A to B.

A

A higher “real income” allows the

consumer to achieve a higher

indifference curve.

The movement from bundle B to C

represents the income effect (IE). The

new equilibrium is achieved at point

C.

II

B

I

0

IE

X

SE

4-20

Giffen Goods

Do all goods obey the Law of Demand?

Suppose the goods are potatoes and meat,

and potatoes are an inferior good.

If price of potatoes rises,

– substitution effect: buy less potatoes

– income effect: buy more potatoes

If income effect > substitution effect,

then potatoes are a Giffen good, a good for which

an increase in price raises the quantity demanded.

4-21

Giffen Goods

4-22

Wages and Labor Supply

Budget constraint

– Shows a person’s tradeoff between consumption

and leisure.

– Depends on how much time she has to divide

between leisure and working.

– The relative price of an hour of leisure is the amount

of consumption she could buy with an hour’s wages.

Indifference curve

– Shows “bundles” of consumption and leisure

that give her the same level of satisfaction.

4-23

Wages and Labor Supply

At the optimum,

the MRS between

leisure and

consumption

equals the wage.

4-24

Wages and Labor Supply

An increase in the wage has two effects

on the optimal quantity of labor supplied.

– Substitution effect (SE): A higher wage makes

leisure more expensive relative to consumption.

The person chooses less leisure,

i.e., increases quantity of labor supplied.

– Income effect (IE): With a higher wage,

she can afford more of both “goods.”

She chooses more leisure,

i.e., reduces quantity of labor supplied.

4-25

Wages and Labor Supply

For this person, SE

> IE

So her labor supply

increases with the wage

4-26

Wages and Labor Supply

For this person, SE

< IE

So his labor supply falls

when the wage rises

4-27

Could This Happen in the Real World???

Over last 100 years, technological progress has

increased labor demand and real wages.

The average workweek fell from 6 to 5 days.

4-28

Interest Rates and Saving

A person lives for two periods.

– Period 1: young, works, earns $100,000

consumption = $100,000 minus amount saved

– Period 2: old, retired

consumption = saving from Period 1

plus interest earned on saving

The interest rate determines

the relative price of consumption when young

in terms of consumption when old.

4-29

Interest Rates and Saving

Budget constraint shown is for 10% interest rate.

At the optimum,

the MRS between

current and future

consumption equals

the interest rate.

4-30

5:

Effects of an interest rate increase

ACTIVE LEARNING

Suppose the interest rate rises.

Determine the income and substitution effects on

current and future consumption, and on saving.

4-31

31

ACTIVE LEARNING

5:

Answers

The interest rate rises.

Substitution effect

– Current consumption becomes more expensive

relative to future consumption.

– Current consumption falls, saving rises,

future consumption rises.

Income effect

– Can afford more consumption in both the

present and the future. Saving falls.

4-32

32

Interest Rates and Saving

In this case, SE

> IE and

saving rises

4-33

Interest Rates and Saving

In this case, SE

< IE and

saving falls

4-34

34

A Classic Marketing Application

Other

goods

(Y)

A buy-one,

get-one free

pizza deal.

A

C

E

D

II

I

0

0.5

1

2

B

F

Pizza

(X)

4-35

Individual Demand Curve

Y

An individual’s

demand curve is

derived from each

new equilibrium

point found on the

indifference curve

as the price of good

X is varied.

II

I

X

$

P0

D

P1

X0

X1

X

4-36

Market Demand

The market demand curve is the horizontal

summation of individual demand curves.

It indicates the total quantity all consumers

would purchase at each price point.

$

Individual Demand

Curves

$

Market Demand Curve

50

40

D1

1 2

D2

Q

1 2 3

DM

Q

4-37

Conclusion

Indifference curve properties reveal information

about consumers’ preferences between bundles

of goods.

–

–

–

–

Completeness.

More is better.

Diminishing marginal rate of substitution.

Transitivity.

Indifference curves along with price changes

determine individuals’ demand curves.

4-38

CONCLUSION:

Do People Really Think This Way?

Most people do not make spending decisions

by writing down their budget constraints and

indifference curves.

Yet, they try to make the choices that maximize

their satisfaction given their limited resources.

The theory in this chapter is only intended as a

metaphor for how consumers make decisions.

It does fairly well at explaining consumer behavior

in many situations, and provides the basis for

more advanced economic analysis.

4-39