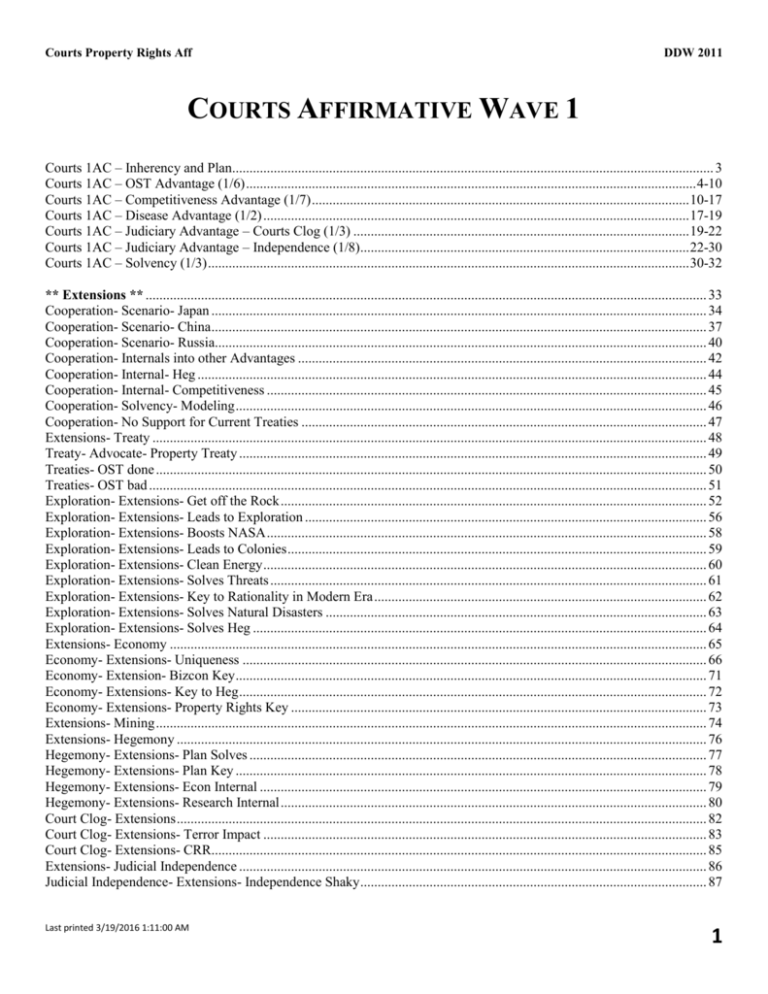

Courts Affirmative Wave 1

advertisement