people resourcing

advertisement

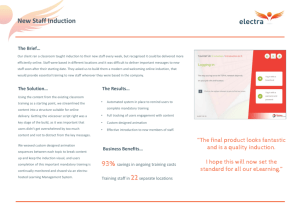

PEOPLE RESOURCING Chapter Thirteen The New Employee Contracts of employment A contract of employment is no more or less than an agreement between two parties to create an employment relationship. It is not necessarily a full written document – it can be a simple offer letter and acceptance, or even an oral agreement. There are four simple legal tests: • Has an offer of employment been made? • Has the offer been accepted? • Does consideration exist? This means that the employee agrees to perform the job and the employer agrees to make payment in the form of wages. • Is there an intention to create legal relations? Once a contract of employment exists, both parties owe certain duties to one another that are enforceable by law. Terms can be either be express, be general to all employment relationships (due to statutory employment legislation), or be ‘implied’. The latter are held to exist by courts even though neither party has formally agreed to them. They may be: • terms implied in common law • the result of custom and practice. Most employers provide evidence in writing of both the existence of the contract and its main terms – to put the relationship on an open, clear footing from the start. Three types of document are often provided: • the offer letter • written particulars of employment • incorporated documents – such as job descriptions, collective agreements and staff handbooks. It is important to note that once procedures are incorporated, an employee has the right to sue the employer if those procedures are not followed. Specific contractual terms Most contracts take a pretty standard form. However, common additional/specific express terms include: • fixed-term clauses – where a termination date must be clearly stated • waiver clauses • probationary clauses • restraint of trade clauses • restrictive covenants. Atypical workers In certain circumstances, it is not easy to determine whether an individual is actually employed by an organisation (under a ‘contract of service’) or is working for them but is in fact self-employed (under a ‘contract for services’). The distinction is significant, however, because a selfemployed person has fewer obligations and rights. The concept of ‘mutuality of obligation’ is employed here when courts are deciding these issues – whether or not the employee is able, in practice, to turn down offers of work without ending the employment relationship. National variations Organisations operating in a number of countries need to comply with local laws in respect of: • who qualifies as an ‘employee’ • the extent to which they permit freely-agreed contracts to form the basis of an employment relationship • special considerations for certain groups (apprentices, homeworkers, etc) • the involvement of trade unions. The psychological contract The psychological contract is concerned with the expectations that employers and employees have of their relationship – these are perceived and exist only in people’s heads. Breaches of the psychological contract on the part of the employer can can result in a loss of employee loyalty and commitment. A common view is that the traditional ‘relational’ contract (where job security and career progression are offered in return for commitment and effort) is being replaced by a ‘transactional’ contract – where the employer offers pay and employment for a limited period in return for the completion of a defined set of duties. The new contract minimises emotion, and resembles a simple economic exchange. Where employers wish to alter the content (or terms) of psychological contracts, they can start by altering the expectations of new employees. The recruitment, selection and induction processes can be key to this. If managers do not take the lead, and expressly communicate their expectations, the psychological contract will be shaped by fellow employees, past employment experiences and general impressions. The most effective approach is for a clear, organisationwide set of expectations to be established and communicated effectively to everyone in the same way. Induction Induction is one of several different terms for activities at the start of an individual’s employment: • Induction is the whole process whereby new employees adjust or acclimatise to their jobs and working environment. • Orientation is a specific course or training event for new starters. • Socialisation is the way new employees build up working relationships and find roles for themselves within their new teams. Effective induction is both difficult to achieve consistently and time-consuming. Poor induction is therefore common, due to a lack of consideration for the new employee’s basic needs. This can lead to high levels of staff turnover in the first months of appointment. Individual employees have widely varying requirements when they join a new organisation, and there are dangers in making blanket assumptions about what information and support each will need. Putting everyone, regardless of rank or experience, through an extensive, identical, centrally-controlled induction programme may well be counterproductive. Effective induction tends to incorporate different activities: • collective orientation sessions – provided for all on the first day • specific small-group orientation sessions in the first weeks • job-/department-specific briefings from the line manager • assigning a mentor or ‘buddy’ to each new employee. When P&D professionals share induction responsibilities with line managers, they will want to develop control systems to ensure that effective induction is actually taking place. The most common mechanism is an induction checklist. Managers have a list of points to cover, and the new employee must sign when the list has been completed. Such documentary evidence is key for organisations seeking to gain/retain the Investors in People (IiP) award. P&D staff are often concerned that line managers do not give sufficient attention to induction processes. Explanations that may be offered include: • that line managers necessarily have a shorter-term focus • that line managers are placed under tight time and cost restraints. Releasing valuable new employees for orientation training is often unpopular • that line managers’ sections of induction are often tedious, and by their nature need to be completed regularly. Many managers try to delegate the task wherever possible. A number of induction features have been found to improve the experiences of new starters: • regular updating of procedures • direct consultation with new starters about programme improvement • keeping induction improvement on the organisation agenda • making use of several communication methods • including job-related training • producing an accompanying ‘welcome’ pack • involving senior management in orientation sessions • covering informal rules and norms as well as the formal ones.