File

advertisement

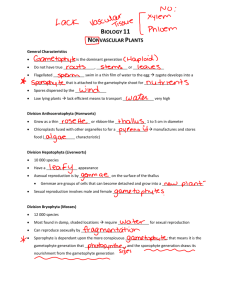

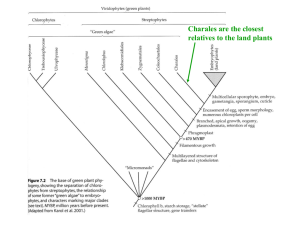

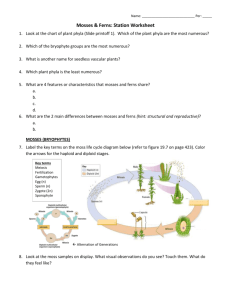

Bryology (mosses, liverworts and hornworts) What are bryophytes? Bryophytes are the oldest land plants on earth, and have been around for 400 million years or more. Although small, they can be very conspicuous growing as extensive mats in woodland, as cushions on walls, rocks and tree trunks, and as pioneer colonists of disturbed habitats. They comprise three main taxonomic groups: mosses (Bryophyta), liverworts (Marchantiophyta) and hornworts (Anthocerotophyta) which have evolved quite separately.Worldwide there are possibly 10,000 species of mosses, 7000 liverworts and 200 hornworts. Most bryophytes have erect or creeping stems and tiny leaves, but hornworts and some liverworts have only a flat thallus and no leaves. How do bryophytes live their lives? Bryophytes have a two-stage life cycle (alternation of generations). The ‘gametophyte' generation is the green photosynthetic part (the familiar moss or liverwort plant) attached to the substrate by threads (rhizoids), and the ‘sporophyte' generation which consists of a stalk and capsule which are dependent on the gametophyte for support and nutrients. Marchantiophyta A division of bryophyte plants commonly referred to as hepatics or liverworts. Most liverworts are small, usually from 2–20 millimetres (0.08–0.8 in) wide with individual plants less than 10 centimetres (4 in) long, so they are often overlooked. The most familiar liverworts consist of a prostrate, flattened, ribbon-like or branching structure called a thallus (plant body); these liverworts are termed thallose liverworts. LIVERWORTS ARE PRIMITIVE One reason liverworts are so curious is that in terms of the evolution of life on Earth, these plants are old. The first liverworts arose as green alga was making its transition onto land during the Devonian Era some 400,000,000 years ago -- and that's a long, long time before more advanced plants such as flowering plants, ferns and mosses appeared. In fact, liverworts are often referred to as "the simplest true plants." Here are some easy-to-see aspects of their primitive nature: • Instead of bearing regular roots, liverworts anchor themselves with rather primitive and simple, onecelled appendages known as rhizoids •Unlike tree leaves which have veins that conduct water, nutrients and other materials, in liverworts there is little or no conducting tissue •Tree leaves have window-like stomata which close when the leaf is threatened with drying out; liverworts have nothing like stomata, so the whole plant shrivels when dry How they Reproduce Liverworts, like all bryophytes, have two forms of reproduction. Asexual or vegetative reproduction, and sexual reproduction. Sexual Reproduction The sexual reproduction for leafy liverworts is very similar to the mosses. The sexual parts are contained in small and inconspicuous structures known as antheridia (male) and archegonia (female), which develop on separate plant bodies. In the thallose liverworts, things are a little different. Marchantia species the antheridia and archegonia are produced on an umbrella like structure. While in others species they are hidden in small pockets on the leafs In leafy liverworts the antheridia produce mobile antherozoids (sperm), which require a film of water in which to move to the archegonia, where fertilisation takes place. After fertilisation, a new plant develops, which remains attached to the parent plant.This is the sporophyte. Asexual Reproduction The gametophyte can propagate itself vegetatively, and also produce the gametes, which give rise to the saprophyte. Vegetative reproduction can occur as a result of older parts of a plant dying off so that the newer branches become separated; by specialised whip-like branches; or by leaves that drop off the plant. In the thallose liverworts a more complicated system is used, with propagative structures called gamma cups forming on the leaves. Each gamma cup gives rise to numerous gametes that are released when water droplets splash into the cup thus transported the gametes to favourable sites to grow into new plants. In most species, a haploid liverwort spore germinates and gives rise to a single-celled protonema, a small filamentous cell. In general, the haploid gametophyte develops from the protonema. In most liverworts, the gametophyte is procumbent, although in some species it is erect. Typically, the gametophyte has a subterranean rhizoid, a specialized single-celled structure which anchors the liverwort to its substrate and takes up nutrients from the soil. Male and female reproductive organs, the antheridia and archegonia, grow from the gametophyte. These arise directly from the thallus or are borne on stalks. About 80% of the liverwort species are dioecious (male and female on separate plants) and the other 20% are monoecious (male and female on the same plant). Each archegonium produces a single egg; each antheridium produces many motile sperm cells, each with two flagella. The sperm cells must swim through water to reach the archegonium. Then, the sperm fertilizes the egg to form a diploid cell. This eventually develops into a multicellular diploid sporophyte. The sporophyte of liverworts, like that of mosses, has a terminal capsule borne on a stalk, known as a seta. As the sporophyte develops, haploid spores form inside the capsule. In general, the sporophytes of liverworts are smaller and simpler in morphology than those of mosses. Another difference is that the liverwort seta elongates after capsule maturation, whereas the moss seta elongates before capsule maturation. The hornwort gametophyte thallus is not much different from a thallose liverwort. The thallus is a onecell-thick sheet at the margins and forms a pad of cells closer to the middle of the thallus. The thallus is irregular in outline and sometimes "frilled" at the margins. Beneath the thallus the lower epidermis anchors itself with rhizoids. Hollow areas of the central pad region may house symbiotic cyanobacteria. These are likely providing a particular mineral nutrient for the hornwort. Archegonia and antheridia are partially or completely embedded in the upper surface of the thallus in the padded central region. Both have sterile jackets which open in response to free water. The sperm are chemotactically attracted to the egg across a film of water trapped on the surface of the pad. The zygote and resulting young sporophyte is initially dependent on the gametophyte for nutrition. The archegonium neck proliferates at the base of the seta and around the foot of the sporophyte. The seta outgrows the neck, however and emerges into the sunlight. It begins to do its own photosynthesis. Its epidermis is cutinized and includes stomata. The cortical layer inside carries out photosynthesis. Surrounding hydroids and leptoids in the center of the seta, are cells which become the sterile jacket and the sporocytes. The latter undergo meiosis to produce spores. As the seta matures, it splits open longitudinally to shed the spores from within. A truly amazing aspect of the sporophyte is that just above the foot the seta is meristematic and can keep making new seta for a long period of time...even after most of the gametophyte has disintegrated! The sporophyte then is more-or-less indeterminate in growth! This is the "horn" of the "hornwort.” The plant body may have conducting tissue and some of this has a familiar look. The xylem-like water-andmineral-conducting tissue is called hydroid. The phloem-like sugar-and-amino-acid-conducting tissue is called leptoid. Mosses are small, soft plants that are typically 1–10 cm (0.4-4 in) tall, though some species are much larger. They commonly grow close together in clumps or mats in damp or shady locations. They do not have flowers or seeds, and their simple leaves cover the thin wiry stems. At certain times mosses produce spore capsules which may appear as beak-like capsules borne aloft on thin stalks. mosses are bryophytes, or non-vascular plants. They can be distinguished from the apparently similar liverworts (Marchantiophyta or Hepaticae) by their multi-cellular rhizoids. In addition to lacking a vascular system, mosses have a gametophyte-dominant life cycle, i.e. the plant's cells are haploid for most of its life cycle. Sporophytes (i.e. the diploid body) are short-lived and dependent on the gametophyte. This is in contrast to the pattern exhibited by most "higher" plants. In seed plants, for example, the haploid generation is represented by the pollen and the ovule, whilst the diploid generation is the familiar flowering plant. The life of a moss starts from a haploid spore. The spore germinates to produce a protonema (pl. protonemata), which is either a mass of thread-like filaments or thalloid (flat and thallus-like). This is a transitory stage in the life of a moss, but from the protonema grows the gametophore ("gametebearer") that is structurally differentiated into stems and leaves. A single mat of protonemata may develop several gametophore shoots, resulting in a clump of moss. From the tips of the gametophore stems or branches develop the sex organs of the mosses. The female organs are known as archegonia (sing. archegonium) and are protected by a group of modified leaves known as the perichaetum (plural, perichaeta). The archegonia are small flask-shaped clumps of cells with an open neck (venter) down which the male sperm swim. The male organs are known as antheridia (sing. antheridium) and are enclosed by modified leaves called the perigonium (pl. perigonia). The surrounding leaves in some mosses form a splash cup, allowing the sperm contained in the cup to be splashed to neighboring stalks by falling water droplets. In the presence of water, sperm from the antheridia swim to the archegonia and fertilization occurs, leading to the production of a diploid sporophyte. The sperm of mosses is biflagellate, i.e. they have two flagellae that aid in propulsion. Since the sperm must swim to the archegonium, fertilisation cannot occur without water. After fertilisation, the immature sporophyte pushes its way out of the archegonial venter. It takes about a quarter to half a year for the sporophyte to mature. The sporophyte body comprises a long stalk, called a seta, and a capsule capped by a cap called the operculum. The capsule and operculum are in turn sheathed by a haploid calyptra which is the remains of the archegonial venter. The calyptra usually falls off when the capsule is mature. Within the capsule, sporeproducing cells undergo meiosis to form haploid spores, upon which the cycle can start again. The mouth of the capsule is usually ringed by a set of teeth called peristome. This may be absent in some mosses. Raindrop 1 Spores develop into threadlike protonemata. Key Male gametophyte Haploid (n) Diploid (2n) Sperm “Bud” 2 The haploid protonemata produce “buds” that grow into gametophytes. Protonemata 4 A sperm swims through a film of moisture to an archegonium and fertilizes the egg. Antheridia 3 Most mosses have separate male and female gametophytes, with antheridia and archegonia, respectively. “Bud” Egg Spores Gametophore Female Archegonia spores develop in the sporangium gametophyte of the sporophyte. When the Rhizoid sporangium lid pops off, the peristome “teeth” regulate 6 The sporophyte grows a gradual release of the spores. long stalk, or seta, that emerges Seta from the archegonium. 8 Meiosis occurs and haploid Peristome Sporangium MEIOSIS Mature Mature sporophytes sporophytes Capsule (sporangium) FERTILIZATION (within archegonium) Calyptra Zygote Embryo Archegonium Foot Capsule with peristome (LM) Female gametophytes Young sporophyte 7 Attached by its foot, the sporophyte remains nutritionally dependent on the gametophyte. 5 The diploid zygote develops into a sporophyte embryo within the archegonium.