Morality and Ethics

advertisement

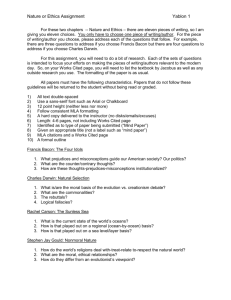

Philosophy 223 Morality and Ethics Some Initial Distinctions and Guiding Concepts Business Ethics? “Ethics” comes from the Greek Ethos (character, custom). Thus, at its most basic, ethics is the study of what it means to be a good person and the rules or norms that appropriately guide our actions. Business: any organization with the primary objective of providing goods and services for profit. Is there any overlap between these two concepts? Yes, there is! As we’ve provisionally characterized it, ethics is the study of a specific set of standards that organize our social experience. Address issues that concern human well being. Have priority over other standards. Legitimacy depends on the adequacy of the justification offered for them. Business is just one form our social experience takes, and there is no reason to believe that the sort of standards studied by ethics don’t apply to business activities. A Key Distinction We often treat “Morality” and “Ethics” as synonyms, but there is an important difference that we need to be alert to. Morality: the actually or historically existing set of social practices defining right and wrong. Not the only set of existing social practices (etiquette). Exists prior (both temporally and in precedence) to any personal or group set. Ethics: reflection on the nature and justification of right action. Attempt to develop “clarity, substance, and precision” (2) in the employment of morality. Morality v. Prudence One problem that moral agents often confront is failing to distinguish the dictates of morality from those of prudence. Prudence: The ability to recognize and follow the most suitable or sensible course of action (OED). The problem arises because we are taught the rules of prudence and the rules of morality at the same time and with the same language. And it is the case that self-interest and moral responsibility often coincide This confusion is endemic in business: “Good Ethics is Good Business.” (See examples on pp.3-4.) Morality v. Law Another set of dictates that is often confused with morality is those of the law. Law: “the public’s agency for translating morality into explicit social guidelines and practices and stipulating punishments for offenses” (4). The difficulty that arises is that, like in all cases of translation, much goes missing. Not everything that is morally obligatory is legally regulated, and not everything that is legally regulated has moral force. (Examples, p. 5). That’s why the common business practice of relying on the lawyers to take the lead on morally troublesome matters is insufficient. The Limitations of Conscience One last claim commonly offered by moral agents of all sorts, including business people, is that all we really need is our conscience. We all have good reason to doubt this if we reflect on our own moral failings. In addition, it’s easy enough to identify instances when our or other’s conscience have led them to morally controversial positions. We have to conclude that, “The reliability of conscience…is not self-certifying” (7). How Can Ethics Help? Ethical reflection on the dictates of morality can address these sorts of issues in at least three different ways. 1. 2. 3. Descriptive analysis of the actual content of morality. Conceptual study of moral concepts. Normative Ethics: “prescriptive study attempting to formulate and defend basic moral norms…aims at determining what ought to be done…[not] what is, in fact, practiced” (7). Applied Ethics: defined “misleadingly” as the use of normative principles “to treat specific moral problems” (8). Defined “Misleadingly” “Applied” encourages a serious misunderstanding: that the attempt to specify (8) the practical implications of normative theory (normative principles) on specific issues involves making moral judgments. Moral Judgments are made by Moral Agents (folks like us, though in a way to be specified). When we are doing ethics (in either sense) we are not actually making such judgments. Rather, we are attempting to identify resources on the basis of which such judgments are made.