View Conference Presentation

advertisement

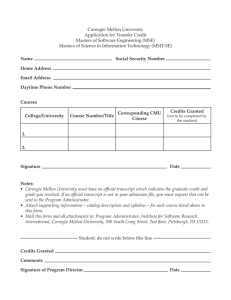

Spatial Analysis of Air Quality Impacts from Using Natural Gas for Road Transportation Fan Tong, Paulina Jaramillo, Ines Azevedo Department of Engineering and Public Policy Carnegie Mellon University 33rd USAEE/IAEE North American Conference Oct 28, 2015 1 Carnegie Mellon University Use Natural Gas to Fuel Transportation? 2 2 Carnegie Mellon University Unintended Consequences? GHGs? • Previous work on greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions • Tong et al. Environmental Science & Technology (2015). • Tong et al. Energy & Fuels (2015). 3 3 Carnegie Mellon University Unintended Consequences of GHGs? Key Factors • Relative fuel efficiency w.r.t. gasoline/diesel vehicles. • Life cycle methane leakage (well pads, gathering lines, processing, pipelines, refueling, vehicle tanks, tailpipe). 15% Current FCEV Break-even methane leakage rate Current CNG vehicle GH2 FCEV, 100-yr Current BEV BEV, 100-yr 10.8% 10% CNG, 100-yr GH2 FCEV, 20-yr 5% 4.5% CNG, 20-yr BEV, 20-yr 2.8% 2.3% 1.2% 0.9% 0% 4 4 100% 150% 200% 250% 300% Energy economy ratio (EERs) of natural gas vehicles 350% 400% Carnegie Mellon University What about Criteria Air Pollutants? • Criteria Air Pollutants (CAP) • Regulated in the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (U.S. EPA). • Particle pollution (often referred to as particulate matter), ground-level ozone, carbon monoxide, sulfur oxides, nitrogen oxides, and lead. • Health and environmental impacts • Of the six pollutants, particle pollution and ground-level ozone are the most widespread health threats. • direct emissions (primary), or • products of chemical reactions (secondary). • Local, certain, near-term impacts. • Health impacts dominate. 5 5 Carnegie Mellon University Research Questions • ‘Best’ use of natural gas? • What are health and environmental damages of natural gas-based fuels in a life cycle sense? • How do they compare with conventional gasoline vehicles? Are there opportunities to reduce the social damages from petroleum use? • Location, location, location? • Are there any good regions or bad regions in particular? How does regional variation affect results? • Do we trust the results? • What cause uncertainty and variability? • How do they impact the results? 6 6 Carnegie Mellon University 7 7 Carnegie Mellon University Comments on Existing Literature • “Fuel pathway comparison” by examining marginal social costs in a life cycle perspective. • Hydrogen (FECVs), biomass (ethanol), electric vehicle, natural gas. • A recent surge of literature (2014-2015). • Almost all focused on passenger vehicles (except NRC (2010)). • Almost all used GREET + APEEP (different versions). • Knowledge gaps? • Environmental damages of trucks, buses and other heavy-duty vehicles? • Near-zero emission engine (0.02 g/bhp-hr) and California’s optional low-NOx standard. • New Marginal damage estimates (social cost of SOx) emgerged. • Emission inventory should be updated. • Real world factors? • Travel speed, road grade, ambient environment - Reyna et al. (2014), Yuksel et al. (2015). 8 8 Carnegie Mellon University Damage Function Method • Marginal damages from life cycle CAP emissions. • Contiguous U.S.; Seasonal & annual average. • Fuel and vehicle focus. • Focus on natural gas pathways • For both LDVs and MHDVs. • Functional Unit. • Normalized damages. • Vehicle mile traveled (VMT). • Passenger mile traveled (PMT). • A ton of cargo moved over one mile (Cargo-ton-mile). • Total damages 9 9 Carnegie Mellon University Build an Emission Inventory • A well-to-wheel emission inventory. Modified from a GREET model presentation (Argonne National Lab) Upstream: extraction of feedstock (e.g., natural gas, crude oil) Production: natural gas -> CNG/LNG/electricity/hydrogen. Transport: from plant sites to refueling stations. Vehicle use: tailpipe emissions. Vehicle manufacturing (e.g. batteries). • Locations of emissions are very important information! • Develop our own emission inventory and compare it with the GREET model. • Source: National Emission Inventory (NEI), peer-reviewed literature. 10 10 Carnegie Mellon University Marginal Damage Estimation • Marginal/incremental damages ($/tonne of pollutant). • Atmospheric chemistry, exposure (intake function), response function, monetary valuation. • APEEP/AP2 model, EASIUR model, BenMAP model, COBRA model. 11 11 Carnegie Mellon University Different Pictures for Passenger Vehicles and Trucks • Fuel pathway comparison with breakdown of life cycle stages. • Median damages in U.S. counties (Unit: cent in year 2000/mile) 12 12 Carnegie Mellon University Benefits of CNG over Gasoline (Passenger Vehicles) 13 13 Carnegie Mellon University Preliminary Conclusions • Choice of natural gas pathway matters. • All natural gas pathways provide some damage reduction potentials but their magnitudes differ. • If NGCC power plant is on the margin, natural gas-electricity-BEV reduces more social damages than CNG. • Vehicle type matters. • Reducing tailpipe emissions is more important for MHDVs than for LDVs. • Location matters. • Across fuel pathways, urban areas (LA, SF, NYC) see much larger normalized damage reductions from natural gas pathways. 14 14 Carnegie Mellon University Acknowledgements • This work is financially supported by • Center for Climate and Energy Decision-Making (CMU & NSF). • 2013-14 Northrop Grumman Fellowship. • 2013-14 Steinbrenner Institute Graduate Research Fellowship. • Fuels Institute. • Fuel Freedom Foundation. 15 15 Carnegie Mellon University Questions? Fan Tong PhD candidate in Engineering & Public Policy ftong@andrew.cmu.edu 16 16 Carnegie Mellon University