PH307-challenger86

advertisement

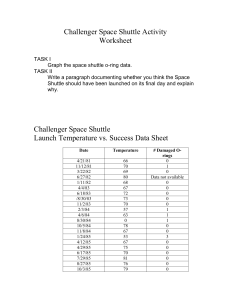

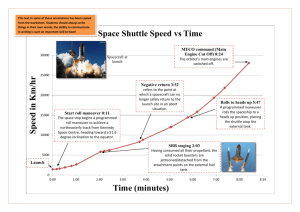

The Challenger Disaster Prof Michael D. Smith School of Physical Sciences (pictures and some text reproduced from NASA sources) Lecture outline • Build-up to the 1986 mission. • Analysis of the Space Shuttle break-up. • Presidential Commission Report. • Conclusions. • Further details. Columbia history Milestones – OV102 July 26, 1972 Contract Award Nov. 21, 1975 Start structural assembly of crew module June 14, 1976 Start structural assembly of aft-fuselage March 16, 1977 Wings arrive at Palmdale from Grumman Sept. 30, 1977 Start of Final Assembly Feb. 10, 1978 Completed final assembly Feb. 14, 1978 Rollout from Palmdale April 12 1981 Launch Jan 16, 2003 28th and Last Flight Challenger history. Construction Milestones - OV-099 (Space shuttle Challenger) Jan. 1, 1979 Contract Award Jan. 28, 1979 Start structural assembly of crew module June 14, 1976 Start structural assembly of aft-fuselage March 16, 1977 Wings arrive at Palmdale from Grumman Nov. 3, 1980 Start of Final Assembly Oct. 21, 1981 Completed final assembly June 30, 1982 Rollout from Palmdale July 1, 1982 Overland transport from Palmdale to Edwards July 5, 1982 Delivery to Kennedy Space Center Dec. 19, 1982 Flight Readiness Firing April 4, 1983 First Flight (STS-6) January 28, 1986 10th and Last Flight Challenger firsts. • Challenger launched on her maiden voyage, STS-6, on April 4, 1983. • That mission saw the first spacewalk of the Space Shuttle program, as well as the deployment of the first satellite in the Tracking and Data Relay System constellation. • The orbiter launched the first American woman, Sally Ride, into space on mission STS-7 and was the first to carry two U.S. female astronauts on mission STS 41-G. Challenger history. Challenger against a backdrop of blue water and white clouds taken from a camera aboard the Shuttle Pallet Satellite during mission STS-7. Background to the mission. 1986 National Aereonautics and Space Administration • This would be the busiest year ever for NASA. • Halley's comet would be observed. • The Hubble telescope lofted. • 25th shuttle flight. • The first average American in space. Shuttle Mission STS-51L: problems Shuttle Mission was plagued by problems from onset. weather conditions technical problems Shuttle Mission STS-51L: delays Challenger was originally scheduled for July, 1985, but by the time the crew was assigned in January, 1985, launch had been postponed to late November to accommodate changes in payloads. The launch was subsequently delayed further and finally rescheduled for late January, 1986. Shuttle Mission STS-51L Launch delays Liftoff was initially scheduled January 22, 1986. It slipped to Jan 23 then Jan. 24, reset for Jan. 25, rescheduled for Jan. 27, but delayed another 24 hours. The Challenger finally lifted off at 11:38:00 a.m. EST, 28th Jan. Shuttle Mission STS-51L Launch delays The first delay of the Challenger mission was due to a weather front expected to move into the area, bringing rain and cold temperatures. Vice President expected to be present for the launch and NASA officials postponed the launch early. The Vice President was a key spokesperson the space program, NASA coveted his good will. Shuttle Mission STS-51L Launch delays The second launch delay was caused by a defective microswitch in the hatch locking mechanism and problems in removing the hatch handle. Once these problems had been sorted out, winds had become too high. The weather front had started moving again, and appeared to be bringing record-setting low temperatures to the Florida area. Mission details Challenger was scheduled to carry some cargo • Tracking Data Relay Satellite-2 (TDRS-2) • Shuttle-Pointed Tool for Astronomy (SPARTAN-203) Halley's Comet Experiment Deployable free-flying module designed to observe Halleys comet using two ultraviolet spectrometers and two cameras. The Crew Back row from left to right: Mission Specialist, Ellison S. Onizuka, Teacher in Space Participant Sharon Christa McAuliffe, Payload Specialist, Greg Jarvis and Mission Specialist, Judy Resnik. In the front row from left to right: Pilot Mike Smith, Commander, Dick Scobee and Mission Specialist, Ron McNair. Mission Highlights (Planned) • Arrive in orbit. On Flight Day 1: • Check the readiness of the TDRS-B satellite. • Deploy the satellite and its Inertial Upper Stage (IUS) booster. • The Comet Halley Active Monitoring Program CHAMP) experiment scheduled to begin. On Flight Day 2: • ”Teacher in space" (TISP) video taping. • Firing of the orbital maneuvering engines (OMS) at 152-mile altitude from which the Spartan would be deployed. Mission Highlights (Planned) On Flight Day 3: • Pre-deployment preparations on the Spartan. • Deployment using remote manipulator system (RMS) robot arm. • Separate from Spartan by 90 miles. • Continue fluid dynamics experiments On Flight Day 4: (started on day 2 and day 3). • Challenger begin to close in on Spartan • Live telecasts by Christa McAuliffe. Mission Highlights (Planned) On Flight Day 5 Rendezvous with Spartan Use the robot arm to capture the satellite. . On Flight Day 6 Re-entry preparations, including flight control checks, test firing of maneuvering jets Crew news conferences also scheduled On Flight Day 7 Prepare for deorbit and re-entry Scheduled to land at the Kennedy Space Center 144 hours and 34 minutes after launch. External Tank Basic shuttle design Right Solid Rocket Booster Left Solid Rocket Booster Orbiter 1. Orbiter • The primary component: • • • • • Length 37.2m Height 17.25m Mass 68.5tonnes Payload:32,000kg Crew: 7 max A reusable, winged craft containing the crew and payload that actually travels into space and returns to land on a runway. 2. External Tank • The External Tank carries liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen in two separate compartments. This is the fuel that is fed to the three orbital engines. The ET is jettisoned at an altitude of 111,400m (365,000ft), and burns-up over the Indian Ocean. External Fuel Tank • Mass: 30 tonnes, empty. • Lift off mass 762 tonnes. • The skeleton of the shuttle vehicle assembly. • The tank holds: 550,000L LOX 1,500,000L LH2 • Only part of the shuttle system to be thrown away. 3. Solid rocket boosters • Without the SRBs, the shuttle cannot produce enough thrust to overcome the earth's gravitational pull. • An SRB is attached to each side of the external fuel tank. • Each booster is 149 feet long (45m) and 12 feet (3.6m) in diameter. • Before ignition, each booster weighs 2 million pounds (900 tonnes, 150 elephants). 80% of the total vehicle mass, 83% of total thrust Solid rocket boosters Solid rocket booster • SRBs, in general, produce much more thrust per weight than their liquid fuel counterparts. • The drawback is that, once the solid rocket fuel has been ignited, it cannot be turned off or even controlled. • Morton Thiokol was awarded the contract to design and build the SRBs in 1974. • Thiokol's design is a scaled-up version of a Titan missile, which had been used successfully for years. • NASA accepted the design in 1976. Solid rocket booster • After the SRBs have lifted the Shuttle to an altitude of about 150,000 ft (45,760 m), the SRBs are jettisoned using small explosive charges. • The SRBs then deploy parachutes • and fall into the ocean. • they are recovered by tugs. O-rings Pressurised joint (exaggerated) Exterior Interior Exterior Interior Pressurised Joint deflection on Solid Rocket Booster Unpressurised joint Solid rocket booster Each SRB joint is sealed by two O-rings: the bottom ring known as the primary O-ring, and the top known as the secondary O-ring. The purpose of the O-rings is to prevent hot combustion gasses from escaping from the inside of the motor. Putty: To provide a barrier between the rubber O-rings and the combustion gasses, a heat-resistant putty is applied to the inner section of the joint. Solid rocket booster O-Rings The Titan booster had only one O-ring. The second ring was added as a measure of safety. Except for the increased scale of the rocket's diameter, this was the only major difference between the shuttle booster and the Titan booster. Typical Space Shuttle mission profile Temperature on day of the launch The air temperature had dropped to -8°C (18°F) the night before and 36°F (2°C) on the morning of the launch. No previous flight had been attempted below 11°C (51°F ), and the manufacturer, Morton Thiokol, had insufficient data on how the boosters would perform at lower temperatures. Although Thiokol engineers were concerned about launching under these conditions and recommended a delay, many felt that the boosters should be able to operate safely even at that low of a temperature. Wind blowing over the ET and impinging on the aft field joint of the right SRB Wind Super-cooled air descending Aft Field Joint O-ring Lower Attachment Strut Cold conditions pre-launch Cold conditions pre-launch It is common procedure for ground personnel to use infrared cameras to measure the thickness of the ice that forms on the ET prior to launch. By chance, the Ice Team happened to point a camera at the aft field joint of the right SRB and recorded a temperature of only 8°F (-13°C), much colder than the air temperature and far below the design tolerances of the O-rings. Had this wind been blowing in almost any other direction and not impinged on the aft field joint, it is likely that the O-rings would have been considerably warmer and the disaster may not have occurred. Cold conditions pre-launch An additional factor was that the information collected by the Ice Team was never passed on to decision makers, primarily because it was not the Ice Team's responsibility to report anything other than the ice thickness on the ET. Had the aft field joint temperature been provided to engineers at NASA and Morton Thiokol, the launch almost surely would've been aborted and the loss of Challenger avoided. Countdown and launch The Challenger was counted-down and lifted-off at 11:38:00 a.m. EST, 28th Jan. O-ring blow-by from the right SRB 0.678 sec O-ring blow-by from the right SRB Eight more distinctive puffs of increasingly blacker smoke were recorded between .836 and 2.500 seconds. The black color and dense composition of the smoke puffs suggest that the grease, joint insulation and rubber O-rings in the joint seal were being burned and eroded by the hot propellant gases. Warning • Roger Boisjoly, a Thiokol engineer had gone on record the night before the launch. • In a teleconference with NASA he stated: • “If we launch tomorrow we will kill those seven astronauts” • He was ignored. O-ring blow-by from the right SRB No further smoke was observed since the joint apparently sealed itself. This new seal was probably due to a combination of two factors: First, the O-rings were heated by the hot burning fuel which would've increased their temperature and resiliency. Second, the solid rocket propellant contains particles of aluminum oxide that melt when heated, and probably sealed the gap. Wind-shear At approximately 37 seconds, Challenger encountered the first of several high-altitude wind shear conditions, which lasted until about 64 seconds. The wind shear created forces on the vehicle with relatively large fluctuations. Wind-shear at max dynamic pressure q At 56 seconds after launch, right around the time of max q …….. Challenger passed through the worst wind shear in the history of the Shuttle program. The wind loads on the vehicle caused the booster to flex and dislodged the aluminum oxide plug that had sealed the damaged O-rings. Variation in air density (r), velocity (V), altitude (h), and dynamic pressure (q) during a Space Shuttle launch. 58.788 s 58.788 s Still photograph of the 51-L launch from a different angle shows an unusual plume in the lower part of the right hand SRB (027). ET damage by SRB The flame continued to grow and became caught up in the aerodynamic flowfield of the accelerating Shuttle. Had this flame been pointed in nearly any other direction, the Shuttle probably could have continued flying safely until booster separation. The mission would however been aborted and the Challenger would have emergency-landed at an abort site. ET damage by SRB THE SRB however pointed towards the ET and eventually caused damage resulting in a leak of the hydrogen fuel. 66.764 s ET damage by SRB At 70 seconds, a circumferential leak of hydrogen appeared about a third of the way up from the bottom of the ET indicating that the hydrogen inner-tank had failed and the ET was disintegrating. Failure of the liquid oxygen tank in the ET 73.124 s The bright luminous glow at the top is attributed to the rupture of the liquid oxygen tank just above the SRB/ET attachment. Challenger is completely engulfed in an incandescent flow of escaping liquid propellant. Structural breakup of the Shuttle 76 s The two SRBs crossed paths and continued operating until 110 seconds after launch, when they were destroyed using onboard self-destruct explosives. Structural breakup of the Orbiter The nose of the Orbiter separates from the crew cabin. The reddish-brown cloud that can be seen emerging from the cloud is the hypergolic nitrogen tetroxide fuel used in the reaction control system (RCS). Structural breakup of the Shuttle 76 seconds into the flight, the Shuttle was travelling Mach 1.92 (equating to a speed over 1,250 mph or 2,040 km/h), at an altitude of 46,000 ft (14,035 m). The continuing rotation of the right SRB pushed the Shuttle off course such that its nose was no longer pointed in the same direction as it was flying. Structural breakup of the Shuttle The stresses these loads created were too great for the Shuttle to bear, and it quickly broke up into several large pieces. 76.795 s 78 s The Challenger's left wing, main engines (still burning residual propellant) and the forward fuselage (crew cabin). Structural breakup of the Orbiter Challenger crew compartment following the break-up Fate of the Crew The momentum of the crew cabin, carried it to an altitude of about 19,525 m (64,000 ft) before it began a free-fall into the ocean. While it is not conclusively known what happened to the crew during this period, it is believed that they probably survived the initial breakup of the Challenger since the loads experienced were only greater than 4 g's for a very brief period. Fate of the Crew The cabin did lose electrical power and oxygen as it separated from the rest of the vehicle. If the cabin was depressurized during this period, it is likely that the crew was knocked unconscious due to lack of oxygen. However, the astronauts were equipped with Personal Egress Air Packs (PEAPs) containing an emergency air supply. Of the four PEAPs recovered, three had been activated and partially used indicating that at least some of the crew survived long enough to turn them on. Fate of the Crew Nevertheless, these PEAPs were not designed for high-altitude use and would not have prevented the astronauts from passing out had the cabin depressurized. Whether they were conscious throughout the 2 minutes 40 seconds descent or not, the cabin impacted the surface of the ocean at 200 mph (320 km/h), creating a force of about 200 g's that would have killed any survivors instantly. Presidential Commission The mandate of the Commission was to: 1. Review the circumstances surrounding the accident to establish the probable cause or causes of the accident; and 2. Develop recommendations for corrective or other action based upon the Commission's findings and determinations. CONCLUSION: joint failure “... the loss of the Space Shuttle Challenger was caused by a failure in the joint between the two lower segments of the right Solid Rocket Motor. The specific failure was the destruction of the seals that are intended to prevent hot gases from leaking through the joint during the propellant burn of the rocket motor. The evidence assembled by the Commission indicates that no other element of the Space Shuttle system contributed to this failure.” CONCLUSION: design failure “Cause of Challenger accident was: failure of the pressure seal in the aft field joint of the right Solid Rocket Booster. Failure due to a faulty design unacceptably sensitive to a number of factors. CONCLUSION These factors were the effects of: temperature, physical dimensions, the character of materials, the effects of reusability, processing and the reaction of the joint to dynamic loading.” (Source: The Presidential Commission on the SSCA Report, 1986 p.40, p.70) Richard Feynman For a successful technology, reality must take precedence over public relations, for nature cannot be fooled. Credit: Time Life Pictures/Getty Images Richard Feynman: altered criteria “If a reasonable launch schedule is to be maintained, engineering often cannot be done fast enough to keep up with the expectations of originally conservative certification criteria designed to guarantee a very safe vehicle. In these situations, subtly, and often with apparently logical arguments, the criteria are altered so that flights may still be certified in time. They therefore fly in a relatively unsafe condition, with a chance of failure of the order of a percent (it is difficult to be more accurate).” Richard Feynman:communication “Official management, on the other hand, claims to believe the probability of failure is a thousand times less. One reason for this may be an attempt to assure the government of NASA perfection and success in order to ensure the supply of funds. The other may be that they sincerely believed it to be true, demonstrating an almost incredible lack of communication between themselves and their working engineers.” Further details Launch delays NASA wanted to check with all of its contractors to determine if there would be any problems with launching in the cold temperatures. Alan McDonald, director of the SRB Project at Morton-Thiokol, was convinced that there were cold-weather problems with the SRBs and contacted two of the engineers working on the project, Robert Ebeling and Roger Boisjoly. Further details O-ring problems Thiokol knew there was a problem with the boosters as early as 1977, and had initiated a redesign effort in 1985. NASA Level I management had been briefed on the problem on August 19, 1985. Almost half of the shuttle flights had experienced O-ring erosion in the booster field joints. Ebeling and Boisjoly had complained to Thiokol that management was not supporting the redesign task force. Further details Organizations/People Involved Marshall Space Flight Center - in charge of booster rocket development Larry Mulloy - challenged the engineers' decision not to launch Morton Thiokol - Contracted by NASA to build the solid rocket booster Alan McDonald - Director of the Solid Rocket Motors project Bob Lund - Engineering Vice President Robert Ebeling - Engineer who worked under McDonald Roger Boisjoly - Engineer who worked under McDonald Joe Kilminster - Engineer in a management position Jerald Mason - Senior executive who encouraged Lund to reassess his decision not to launch. Further details Pressure to launch NASA managers were anxious to launch the Challenger for several reasons, including economic considerations, political pressures, and scheduling backlogs. • Unforeseen competition from the European Space Agency put NASA in a position in which it would have to fly the shuttle dependably on a very ambitious schedule to prove the Space Transportation System's cost effectiveness and potential for commercialization. • This prompted NASA to schedule a record number of missions in 1986 to make a case for its budget requests. Further details Pressure to launch • The shuttle mission just prior to the Challenger had been delayed a record number of times due to inclement weather and mechanical factors. • NASA wanted to launch the Challenger without any delays so the launch pad could be refurbished in time for the next mission, which would be carrying a probe that would examine Halley's Comet. If launched on time, this probe would have collected data a few days before a similar Russian probe would be launched. • There was probably also pressure to launch Challenger so that it could be in space when President Reagan gave his State of the Union address. Reagan's main topic was to be education, and he was expected to mention the shuttle and the first teacher in space, Christa McAuliffe. Further details Key Dates 1974 - Morton-Thiokol awarded contract to build solid rocket boosters. 1976 - NASA accepts Morton-Thiokol's booster design. 1977 - Morton-Thiokol discovers joint rotation problem. November 1981 - O-ring erosion discovered after second shuttle flight. January 24, 1985 - shuttle flight that exhibited the worst O-ring blowby. July 1985 - Thiokol orders new steel billets for new field joint design. August 19, 1985 - NASA Level I management briefed on booster problem. January 27, 1986 - night teleconference to discuss effects of cold temperature on booster performance. January 28, 1986 - Challenger explodes 72 seconds after liftoff. Improvements 1. redesign of the SRB O-ring joint seals 2. addition of a crew escape system 3. greater restrictions on conditions in which the Shuttle can be launched These measures proved effective until 2003 when the Columbia was lost It is interesting to note that one of the key factors in the Challenger disaster was: the worst wind shear ever experienced by a Shuttle, and Columbia happened to experience the second worst wind shear in history a factor that played a key role in its eventual loss as well.