Social Identity Theory: Tajfel's Concepts & Studies

advertisement

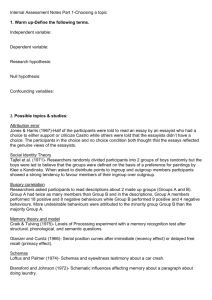

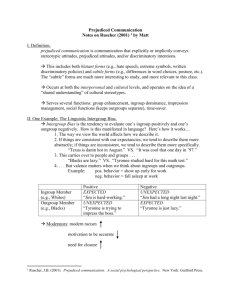

Social Identity Theory Self-concept • A cognitive representation of the self, which coordinates an individual’s selfperception. • People categorize and evaluate themselves based on physical characteristics and skills as well as social categories (e.g. gender, and ethnicity) • Self-esteem: based on evaluation of self along a positive-negative continuum (positive and negative selfconcept). Jette Hannibal Inthinking 2011 Turner (1982) Self-categorization Theory Turner distinguished between one’s personal identity and one’s social identity. Identity is the result of categorization – for example, gender, ethnicity, or nationality. Jette Hannibal Inthinking 2011 Social identity • Part of an individual’s self-concept comes from knowledge of his or her membership of a social group including the value and emotional significance related to that group membership. Social Identity Theory (Tajfel) Definition: Social identity theory proposes that the membership of social groups and categories forms an important part of our self concept. Therefore when an individual is interacting with another person, they will not act as a single individual but as a representative of a whole group or category of people. Even during a single conversation an individual may interact with another person both on a personal level and as a member of a particular group. Social Identity Theory (Tajfel) • Social Comparison – drives self esteem • Positive distinctiveness: showing our ingroup is superior to outgroup Ethnocentrism • +ve ingroup behaviours – dispositional • -ve ingroup behaviours – situational • +ve outgroup behaviours – situational • -ve outgroup behaviours – dispositional Social Identity Theory (Tajfel) Intergroup Behaviours (continued): Ingroup favouritism Intergroup differentiation – behaviour emphasising differences between ingroup and outgroup Stereotypical thinking – ingroupers/outgroupers perceived according to stereotypes Conformity to ingroup norms Depersonalization – see others not in terms of their individual identity – but collectively as part of their group Social Identity Theory (Tajfel, 1971) There are three fundamental psychological mechanisms underlying social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner 1979). Social Identity Theory (Tajfel) Social Categorisation: the process whereby objects, events and people are classified into categories. By doing so we tend to exaggerate the similarities of those in the same group and exaggerate the differences between those in different groups • The more important and meaningful the category membership, the more it forms the basis of an individual’s social identity. • Individuals strive for a positive selfconcept and therefore also a positive social identity. Social Identity Theory (Tajfel) Social comparison: the process of comparing one’s own social group with others. Some social groups have more power, prestige or status than others and therefore members of a group will compare their own groups with others and determine the relative status of their own group. • This also results in the tendency for members of a group to distance themselves from membership of a group which does not share the same beliefs and ideas of their group and take more account of the beliefs and ideas of their social group. • Social comparison may contribute to positive distinctiveness (feeling better than the out-groups) or the opposite (negative distinctiveness). • Discrimination can be seen as a way of establishing positive in-group distinctiveness. Social Identity Theory (Tajfel) Group membership as a source of positive self esteem. Maintaining positive self esteem is seen as a basic motivation for humans therefore if a group does not compare favourably with others we may seek to leave the group or distance ourselves from it. However if leaving the group is impossible then people may adopt strategies such as comparing their own group to a group of a lower status. Social Identity Theory (Drivers) Self-enhancement intergroup differentiation enhances self-esteem Collective (rather than personal) self-esteem Group membership makes people highly creative in protecting against low self-esteem Uncertainty reduction Helps define relationships with others and sets out how others will act Provides a clear sense o self Social Identity Theory (Other components) Referential informational influence theory (conformity & group polarization) Social attraction hypothesis (cohesion & attraction in groups) SIT of deindividuation phenomena Collective guilt (feeling guilty about the actions of other group members in the past) Social Identity Theory (Other components) Deindividuation Deindividuation into a group results in a loss of individual identity and a gaining of the social identity of the group. When two groups argue (and crowd problems are often between groups), it is like two people arguing. When you are in a group, you may feel a shared responsibility and so less individual responsibility for your actions. In this way a morally questionable act may seem less personally wrong. You may also feel a strong need to conform to social norms. Social Identity Theory (Other components) Deindividuation The three most important factors for deindividuation in a group of people are: • Anonymity, so I can not be found out. • Diffused responsibility, so I am not responsible for my actions. • Group size, as a larger group increases the above two factors. Tajfel (1970) minimal group paradigm • Aim: To investigate if intergroup discrimination could take place based on being randomly allocated to different groups based on arbitrary categories. • Procedure: Two experiments with UK schoolboys who were randomly placed in groups based on results of an initial task. In the second experiment they were categorized based on their artistic preferences. Then they were asked to give small amounts of money to the other boys. • Results: The majority of the boys gave more money to boys in their own group (in-group favouritism). In the second experiment the boys also tried to maximize the difference between the ingroup and the out-group (discrimination) • Evaluation: The lab experiment suffers from artificiality and demand characteristics. The theory is rather reductionist. Howarth (2002) • Aim: investigate how social representations of being from Brixton affected the social identity of adolescent girls. • Procedure: Qualitative focus-group interview to investigate social representations in the ingroup (people from Brixton). • Results: The girls from Brixton did not share the negative representation of “being from Brixton” that people outside the city held (stereotype/prejudice). People from Brixton had a positive social identity, seeing themselves as “diverse, creative, and vibrant.” • Evaluation: The study lends support to social identity theory (positive social identity). The qualitative approach provides in-depth understanding of the participants’ self-perception, which could not have been obtained under experimental conditions. The study has high ecological validity. Other studies Maass (2003) carried out a laboratory experiment to investigate the hypothesis that threat to male identity would increase the likelihood of gender harassment. In the experiment a computer harassment paradigm was used - that means, a situation was simulated on the computer which would allow a male to sexually harass a "virtual female" in order to avoid the ethical considerations of using a real female participant. Results show that (a) participants harassed the female interaction partner more when they felt threatened; (b) this was mainly true for highly identified males; and (c) harassment enhanced post-experimental gender identification. Results are interpreted as supporting a social identity account of gender harassment. Other studies Cole, Kemeny & Taylor (1997) carried out a study on the role of SIT on the health of HIV infected gay men. HIV infected gay men were ranked on their "rejection sensitivity" - that is, the extent to which they felt that they were subject to homophobia and rejection by their local community or "in-group." The researchers analyzed data for a 9 year prospective study of 72 initially healthy HIV positive males and found that those with high "rejection sensitivity" showed a significantly faster rate of T cell depletion, diagnosis of "full blown AIDS" and HIV related mortality. Those who were not in homophobic, unaccepting environments - or those who were not "out" to their community - did not show this acceleration of symptoms. Cross Cultural Differences Wetherall (1982) compared three samples of 8 year old children – New Zealanders of European origin; Maori (indigenous); Samoan (islander) immigrants. They randomly split the children into groups. All groups were given Tajfel matrices. European background maximised the difference between ingroup and outgroup. Samoans maximised rewards evenly between two groups. The Maori results were mixed. Collectivist culture of the Samoan may explain why the children did not perceive fellow Samoans as ingroup or outgroup. Could also be due to the importance of gift giving – giving more raises the status and prestige of the ingroup. Or it could be that the white experimenters procedures may have just been to strange. Cross Cultural Differences Kitayama et al. (2003) found cross-cultural differences in ingroup bias between Americans and Japanese students. The strength of this study is that the hypothesis was tested in the openly competitive, emotionally charged contexts that are known to exacerbate in-group bias. They compared amount of in-group bias among students before and after a university football match between two Japanese teams and between two American teams. The results revealed that both American teams showed ingroup bias through evaluations of their universities. Japanese ratings on the other hand, reflected the universities’ status in the larger society. Evaluation of SIT The theory has high heuristic validity - that is, it can be used to explain a variety of human behaviours. There does seem to be biological support for this. Hart et al (2000) and Fiske (2007) both observed activity in the amygdala when participants were shown images of racial out-groups while in an fMRI. This may provide biological support for the process of social categorization into in-groups and out-groups. We all have a lot of different social identities. The theory does not predict well which identity will determine our behaviour. In the case of sexuality, the theory may explain why a particular child may become lesbian, but it does not account for all the others that do not. Much of the research is non-experimental. It is based on anecdotal evidence - for example, Drury et al's stories of survivors of disasters or on correlational data. Evaluation of SIT • • • Many of the early studies lacked ecological validity, but there are many studies that have been done in a naturalistic environment. The theory does not look at dispositional factors. For example, in the Tajfel & Turner study, some people may be more competitive. • Environmental factors, such as war or poverty, may play a greater role. • Self-esteem may not play as great a role as once thought. It may be an initial reason for identifying with a group, but it does not appear to be sustainable. • Social groups in real life are normally not of a minimal nature. Group members use more information about the social context than mere categorization • Overly theoretical and difficult to refute. Cannot predict when someone’s individual identify will supercede that of the group The theory does not look at cultural factors. Collectivistic societies tend to be less consistent in this behavior. • Has high heuristic validity – that is, it can be used to explain a lot of things. • Why does some out-group discrimination lead to violence? Sherif said it was about limited resources. Is this a valid claim?