Local Residential Sorting and Public Goods Provision

advertisement

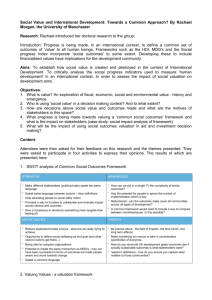

Local Residential Sorting and Public Goods Provision: A Classroom Demonstration Keith Brouhle, Jay Corrigan, Rachel Croson, Martin Farnham, Selhan Garip, Kenyon College Luba Habodaszova, Laurie Johnson, Martin Johnson, and David Reiley Introduction The Demonstration Students in undergraduate public finance courses learn that markets generally underprovide public goods due to the nonexcludable and nonrival nature of those goods. But centralized government provision of locally-consumed public goods may also be inefficient due to heterogeneous preferences. This classroom exercise illustrates the Tiebout hypothesis that residential sorting across multiple communities leads to a more efficient allocation of local public goods (Journal of Political Economy 1956). The exercise also demonstrates problems that arise when certain assumptions of the Tiebout model are not met. By allowing students to uncover the subtleties of the model themselves, this demonstration helps students develop a richer understanding of the model’s real-world implications and the importance of its underlying assumptions. The classroom initially comprises a single community of students with heterogeneous preferences for a public good (dorm parties); the students determine the level of taxation to be used for public good provision via a simple voting mechanism. Next, the classroom divides into two dorms, each of which determines its own level of public good provision. Then the students have the opportunity to relocate to the dorm where the bundle of public goods and taxes better suits their tastes. At first some students must stay in their original location, but in the final treatment all students are free to move. After each round of sorting, each dorm determines a new level of public good provision. Students see how welfare rises as sorting becomes more complete. This game highlights the usefulness of markets in general and the assumptions necessary for a well-functioning market to reach an efficient outcome. The third round of the exercise may foster classroom discussion about “white flight” from inner-city school districts, as it shows how some immobile individuals become worse off when mobile individuals move. The classroom demonstration takes about thirty minutes, which leaves time for class discussion afterward. The demonstration will work in classes with as few as six students or as many as 100 students. While designed primarily for a public finance course, the exercise can be used in any course that covers government provision of public goods. The demonstration follows students through four years of college as they choose (or are assigned) a dorm in each successive year. The only thing that differentiates students is their preferences regarding dorm parties, a local public good. And since each dorm’s residents determine the size of their dorm’s party budget, the dorms differ only in the bundle of taxation and public good provision offered. At the beginning of the exercise, each student receives a color-coded packet of materials (available from the presenter). Students with blue instructions are High Valuers who value dorm parties at 2×T, where T is the level of taxation dorm residents agree to. Students with red instructions are Low Valuers who value parties at 0×T. Each year, a dorm’s residents must collectively choose a level of taxation T between $0 and $100 that each student will pay. These taxes are spent collectively to sponsor dorm parties. Since we assume that a unit of dorm parties costs $1, for High Valuers the marginal benefit from contributing always exceeds the marginal cost, while for Low Valuers the marginal cost always exceeds the marginal benefit. The two colors of packets should not be evenly distributed between the two sides of the classroom. For example, two-thirds of the packets on the right side of the room should be red, while two-thirds of the packets on the left side of the room should be blue. Half of the packets (both red and blue) should also contain a green ticket. This ticket determines whether students will be able to change dorms in Year 3. Year 1 All students begin the demonstration as residents of one dorm. Using a simple voting mechanism, they collectively determine that dorm’s level of taxation and subsequent public good provision. Year 2 Year 3 The instructor breaks the class up into two dorms, one made up predominately of High Valuers, the other made up predominately of Low Valuers. Each dorm then determines its own level of public good provision. The dorm made up largely of High Valuers should choose a level of taxation and public good provision that is higher than that chosen by the other dorm. Those students who were initially endowed with a green ticket are given the option to move from one dorm to another. Each dorm again determines its own level of public good provision. Taxation and public good provision should rise in the High Value dorm and fall in the Low Value dorm. One Dorm Hi Hi Lo Hi Hi Lo Hi Hi Hi Lo Lo Lo Hi Lo Lo Lo Lo Hi Lo Lo Hi Lo Hi Lo Lo $50 votes 4 Hi $0 votes 13 Total votes 30 Tax level (T) $50 Dorm after-tax welfare 30000 Year 1 social welfare = 30000 Left: $100 votes 10 Hi Lo Hi Lo Hi Hi Lo Hi $50 votes 0 $0 votes 5 Total votes 15 $50 votes 0 Hi Hi Lo Hi # moving Left = $0 votes 2 Right after-tax welfare 14853 Lo Hi # moving Right = 2 # moving Left = 2 Total votes 15 Left: $100 votes 15 $0 votes 0 Total votes 15 $0 votes 15 Total votes 15 $50 votes 0 Right: $100 votes 0 $0 votes 13 Lo 3 Right: $100 votes 2 Right after-tax welfare 14833 Lo Lo Right: $100 votes 10 Year 1 social welfare = 30000 Year 2 social welfare = 30166 Lo Lo Hi Lo Left after-tax welfare 16500 Right tax level (TR) $13 Lo Hi Hi Left after-tax welfare 15953 Right tax level (TR) $33 Lo Hi Left after-tax welfare 15333 $50 votes 0 Lo Hi Lo Left tax level (TL) $100 Total votes 15 Hi Hi Left tax level (TL) $87 $0 votes 5 Lo Lo Hi Lo Left tax level (TL) $67 $50 votes 0 Lo Lo Hi Lo Left: $100 votes 13 Hi Lo Lo Hi # moving Right = 3 $100 votes 13 Hi Hi Hi Lo Hi Lo Lo Lo Lo Hi Right Lo Lo Lo Hi Hi Lo Hi Lo Hi Hi Hi Left Hi Hi Hi Hi Lo Hi Hi Lo Lo All students are now free to move to whichever dorm best reflects their preferences. Each dorm determines its level of public good provision one last time. The predictions of the Tiebout model should be fully realized. Right Lo Lo Hi Lo Lo Lo Lo Left Hi Hi Hi Hi Hi Hi Hi Hi Lo Lo Right Lo Lo Hi Hi Left Year 4 Total votes 15 Year 1 social welfare = 30000 Year 2 social welfare = 30166 Year 3 social welfare = 30806 $50 votes 0 Right tax level (TR) $0 Right after-tax welfare 15000 Year 1 social welfare = Year 2 social welfare = Year 3 social welfare = Year 4 social welfare = 30000 30166 30806 31500 Topics for Discussion You may want to begin discussion by focusing on how individual and social welfare change over successive years. By the end of Year 4, most students realize that when similar individuals sort into communities according to their taste for a public good, social welfare is maximized. You can then emphasize the implications of relaxing the model’s assumptions. What happens if there are more than two types of residents but only two communities? Or what if a single household belongs to multiple local-public-good communities? Will efficient levels of provision be reached? You can also ask students to discuss their own experience with residential choice and the communities in which they have lived. How did their families decide where to live? Did the quality of schools or other local public goods (e.g., fire protection, parks) play a role? Do they believe everyone in their community wants exactly the same things from the local government? In other words, just how complete is the residential sorting they observe in the real world? Perhaps most interesting is a discussion of the costless mobility assumption. Students should be able to come up with several reasons why moving might be costly. Faced with such costs, some low-income residents will not be able to afford to move. Other residents may need to live near where they work. For others, non-pecuniary costs may be more important. For example, many people value living near their relatives and friends, or simply don’t like having to adjust to a new environment. In this case, sorting is incomplete and the equilibrium outcome is inefficient.