Educational Master Plan - California Community Colleges Chief

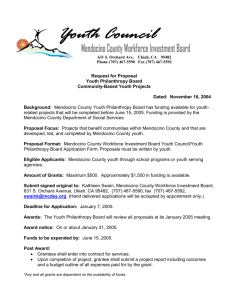

advertisement