the paper

advertisement

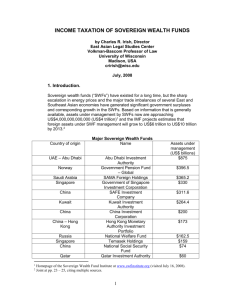

Sovereign Wealth Funds: Issues and Challenges Mukul Asher Professor of Public Policy National University of Singapore Email: sppasher@nus.edu.sg Prepared for the seminar at National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies, Tokyo, July 2008. Organization • • • • • • • Defining Sovereign Wealth Funds (SWFs) Size of SWFs Benefits of SWFs Concerns Recent Developments Future Trajectory Concluding Remarks 2 Defining SWFs • Sovereign Wealth Funds (SWFs) are one of the separated pools of assets (primarily but not exclusively internationally invested) owned by governments to achieve economic, financial, and strategic objectives. • Usually, SWFs are separated from the country’s foreign exchange reserves. There are wellestablished norms for investing foreign exchange reserves, but not for SWFs. 3 Defining SWFs • They are also separated from government financial and non-financial corporations, purely domestic assets, and assets owned and controlled by subnational unit. 4 Defining SWFs • IMF (2008) classifies SWFs into 5 groups: – Stabilization Funds (designed to insulate the budget and the economy against commodity price swings) – Savings Funds for Future Generations (to enable conversion of non-renewable assets into a more diversified portfolio of assets and mitigate the effects of Dutch disease) – Reserve Investment Corporations (these assets are still counted as reserve assets and are established to increase the return on reserves, though at a higher risk) 5 Defining SWFs – Development Funds (designed to help fund socio-economic projects and infrastructure. These funds usually have large domestic component) – Contingent Pension Reserve (particularly to finance social security and health expenditures for rapidly ageing populations) To the extent SWFs assets accrue because of persistent and large structural budget surpluses, they indicate overtaxing and/or underspending by the concerned governments, which reduces current taxpayers welfare (Nageswaran, 2008). 6 Defining SWFs • The vastly expanded number, scale and scope of activities of the SWFs is a relatively new phenomenon, though they have existed for several decades. Their structure, mandates, and objectives however vary. • Some have termed SWFs as important symbol of state capitalism. 7 Size of SWFs • There are no robust databases which monitor the financial flows of the SWFs. Therefore, the estimates of the size of the SWFs vary widely. • Table 1 divides SWFs into non-pension funds (with assets of USD 3 trillion); and pension funds with assets of USD 2.3 trillion for a total of USD 5.3 trillion. • Some projections indicate that assets of SWFs will surpass the economic output of the US by 2015, and the EU by 2016. 8 Table 1: Sovereign Market Estimates of Assets Under Management for SWFs (As of February 2008) (In billions of US dollars) Source: Truman (2008) 9 Size of SWFs • The SWFs are one of the two identifiable pools, the other being foreign exchange reserves. • Table 2 suggests that the reserves are larger than the SWF assets, the combined amount being about $ 8.6 trillion. 10 Table 2: Foreign Exchange Reserves and Sovereign Wealth Funds Billions of U.S. dollars Country Foreign Exchange Reserves Sept. 2007 SWF Total Japand Chinad United Arab Emiratese Singapored,e,r Norway Russiar United Statesd Saudi Arabias Netherlandsd Canadad Taiwan Korear India Kuwait Hong Konge,r Brazil Algeria Malaysiad Libyad,e Mexico 923 1,434 43 152 59 415 44 30 9 39 263 257 240 18 141 163 100 98 74 81 974 263 724 323 357 144 299 275 291 252 – 20 – 213 127 – 46 18 40 5 1,897 1,696 767 423 416 415 344 305 300 292 263 255 240 231 165 163 146 116 114 86 Total 4,582 4,372 8,633 d = A portion of SWF holdings is in domestic assets. e = Size of SWF is estimated. r = Reserves include SWF in whole or in part using estimates for Singapore and Hong Kong. s = The "SWF" is non-reserve holdings of international securities reported by the Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency. Source: Truman (2007) 11 12 Figure 1: China's Foreign Exchange Reserves (1992-2006) Percent of GDP USD Billions 1,200 50 45 1,000 40 35 800 30 25 600 20 Percent of GDP 400 15 USD Billions 10 200 5 0 0 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 Source: Truman, E. (2007), “The Management of China’s International Reserves: China and a SWF Scoreboard”, Paper Prepared for Conference on China’s Exchange Rate Policy Peterson Institute for International Economics, November 17. 13 Size of SWFs • Table 3 puts these amounts in perspective in terms of global financial assets. • In 2006, global financial assets were $190.4 trillion, so SWF assets ($4.4 trillion from Table 2) are about 2.3 percent of the total; and 8.7 percent of global stock market capitalization. In May 2008, the global stock market capitalization was $85 trillion, and correspondingly value of other financial assets are likely to be higher. • The above figures however understate the importance (at the margin) of government controlled pool of funds, represented by SWFs and foreign exchange reserves. • The SWFs are large and are projected to become more prominent in the future. The World in general, and individual countries will therefore need to learn to adjust to them, and minimize their possible adverse impacts. 14 Table 3: Selected Indicators on the Size of the Capital Market (2006), In Trillions of US Dollars Source: IMF (2008) 15 • Truman (2008) reaches the following conclusions with regard to the impact of SWFs on the US : 1. SWFs pose little threat to US security and economic interests. 2. SWFs are part of global economic and financial changes. It is imperative that appropriate policies are formulated regarding SWFs. 3. US ought to minimize economic and potential barriers to foreign investment in all forms and various sources. Financial protectionism is bad for the US and the world economy. 16 • While the US has the capacity to manage the impact of the SWFs, this may not necessarily be the case for the other countries, particularly those with limited financial and capital markets, and low to moderate levels of regulatory capacity. • The sheer size and scale of the SWFs strongly suggest that precautionary principle, in this case assuming that non-economic considerations will apply in their behavior, at least in some investment decisions which may be undertaken for global influence, should be applied with respect to SWFs. • Emergence of China as a major creditor country may adversely impact on the market dominance enjoyed by the US and other Western financial institutions in the medium term; and may fundamentally alter the Bretton Woods institutions – the IMF and the World Bank. 17 Benefits of SWFs Main benefits of SWFs are: For home countries, – They facilitate intergenerational transfer of proceeds from nonrenewable resources, and assist stabilization; – Permit consumption and tax smoothing across generations; – Potentially enable prudent diversification of assets; – In some countries, a national holding company is established to manage state enterprises and oversee their acquisition of strategic stake in key foreign companies; while ensuring that domestic state enterprises and other strategic companies are not acquired by foreign interests. – Could enable a portion of excess foreign exchange reserves to be segregated for pursuing higher risk appetite and potentially obtain higher returns. This may help reduce the cost of sterilization. 18 Benefits of SWFs For international financial markets, – They facilitate a more efficient allocation of revenues from commodity surpluses across countries; – Help recycle current account surpluses, and enhance market liquidity (this is of some importance currently due to global financial stress); – Have longer time horizons which may bring stability. – Permit more diversified partnership with other players such as private equity and hedge funds, permitting better risk management – They now compete with Central Banks, hedge funds, private equity as the international capital providers of last resort. 19 Concerns • Global Macroeconomic Stability and Sustainability – There are global macroeconomic imbalances in which overconsumption by the United States, and mercantilist policies of NorthEast Asian countries, particularly China, play an important role. – So, continued acquisition of excess reserves by them, combined with policies to maintain under-valued currencies, will perpetuate such imbalances and adversely impact on financial stability of rest of the world. – This is somewhat mitigated by provision of liquidity that the SWFs can potentially provide. (This assumes that accommodating policies of the central banks are appropriate). 20 Concerns • The concentration of SWF investments in financial institutions where the agency problems have been particularly acute (as evidenced by the sub-prime crisis and exploitation by banks and other financial institutions of regulatory loop holes) could create greater systemic risks, and contingent liabilities for the tax payers who are the ultimate principals. • Transparency and Accountability – Largest share of SWF assets is with the countries in which the state has played a dominant role in the society and the economy; and where representative institutions designed for checks and balances are relatively less established. – In these countries, information is regarded as a strategic resource, rather than a public good. – The transparency and accountability concerns are also relevant for the domestic population of countries of SWF, as this may adversely impact on their welfare. 21 Concerns – This concern is also present for some of the other financial players such as hedge funds, and private equities. – Truman (2008) has ranked selected SWFs according to structure, governance, transparency and accountability, and behavior criteria (Table 4). 22 Concerns (Table 4) Source: Truman (2008) 23 Table 5: SWF Scorecard Source: Truman (2008) 24 Table 5 (Continued) Source: Truman (2008) 25 Table 5 (Continued) Source: Truman (2008) 26 Table 5 (Continued) Source: Truman (2008) 27 Concerns • It is interesting to observe that pension SWFs score substantially higher than the non-pension SWFs. • The score for behavior is especially low for non-pension SWFs. • The top-twelve SWFs are all from industrial countries, while the bottom-twelve are from oil-producing countries. 28 Concerns • There has been a debate about the desirability of reciprocity. Some have argued that providing SWFs access to recipient countries is advantageous (subject to prudential safeguards) even if there is no reciprocity. Thus, Rachman (Financial Times, April 29, 2008) argues that “China, Russia, and the Middle East have large investments in the US and the EU, then they also have a direct stake in the continuing prosperity of America and the EU”. Truman (2008) has also made similar arguments. • The others have observed that many countries with the SWFs have restrictive investment, and service sector regimes. They are therefore accessing more liberal regimes abroad while denying the other countries corresponding access to their economies. 29 Concerns • Conflicts of Interest, Potential Insider Trading, and Regulatory Effectiveness – Conflicts of interest could arise when governments which are regulators and protect public interest from fraudulent and anticompetitive behavior, become investors. – SWFs as government agencies could have access to commercial and security sensitive information. This could also lead to insider-trading. 30 Concerns • As SWFs are controlled by the governments, prosecuting officials of foreign governments could pose a diplomatic dilemma, reducing effectiveness of domestic regulation. 31 Recent Developments • As the SWFs are likely to be important players in the international financial and capital markets, Code of Governance is needed. The SWFs are simply too big and their definition is too imprecise to be formally regulated. • As data on SWFs are not systematically collected, national and international efforts are also needed in this area. Similar data gathering efforts are also needed for hedge funds and private equity. • The IMF, The World Bank, and the OECD have been asked by G-7 to examine SWF issues and to draw up broad guidelines for both the home and recipient countries. The aim is to reap the benefits of SWF investments, while safeguarding national security and other concerns but without harmful protectionism. 32 Recent Developments • IMF’s Global Financial Stability Report has been covering SWFs, hedge funds and private equity funds • IMF (2008) has set up a Work Agenda, primarily for fund surveillance for developing a draft of SWF principles and practices, including disclosure, reporting, transparency and governance. IMF board has endorsed the work agenda on March 21, 2008. • In March 2008, US Treasury reached agreement with SWFs of Abu Dhabi and Singapore on policy principles for SWFs and for countries receiving SWF investments. Abu Dhabi’s Mubadala fund has already applied for credit rating, and is arguing that it should not be labeled as SWF. • In April 2008, representatives of two dozen SWFs met at the IMF for discussions. • U.K . Hedge Fund Working group and Private Equity Working Group are also developing transparency and disclosure codes on voluntary basis. 33 Recent Developments • Germany has decided to create an agency similar to Committee on Foreign Investments in the US (Cfius) (Financial Times, April 10, 1008, p.6). • The Committee will have the right to review and possibly veto acquisitions by SWFs which may pose a threat to national security or public order. • Acquisitions involving a stake in a German company of more than 25 percent will potentially come under scrutiny. 34 Recent Developments • SWFs from other European Union countries are excluded. • OECD concurs with the German approach arguing that it strikes reasonable balance between need to protect strategic sectors from investors with non-commercial objectives and need to keep markets for investments open. • The US treasury is considering reviewing the provision that if an SWF has less than 10% investment in US financial firms, the investment does not need to be reviewed by CFIUS (WSJ, April 23, 20008). • China Investment Corporation (CIC) is China’s USD 200 billion SWF. It plans to invest up to 90 billion dollars on assets abroad. It has been appointing global managers to manage some of the CIC funds. 35 Recent Developments • Russia’s National Wealth Fund (Assets of USD 33 billion as of May , 2008) plans to take riskier equity position outside of Russia. Its assets are projected to grow to USD 250 billion by 2012. (White et al., 2008). • Russia also has other SWFs and such as the reserve funds (assets USD 130 billion on May 1, 2008) which is invested in more conservative securities outside Russia. • In addition, Russia has many state-controlled companies which also have been aggressive in acquiring assets abroad. • The Russian SWFs and state companies have raised concerns in US and Europe (White et al., 2008). 36 Recent Developments • The Brazilian government plans to use revenues from newly discovered oil fields to create a SWF containing US$200-300 billion in next 3-5 years (Financial Times, June 9, 2008). • It will initially resemble a fiscal stability fund, setting aside 0.5 percent of GDP as a counter-cyclical contingency reserve. It will buy locally issued government debt, thus reducing the debt held by the private sector. 37 Future Trajectory Source: Miracky et al. (2008), p.58 38 Concluding Remarks • SWFs are large, growing, and will continue to play an important role in global financial and capital markets. • Their growth reflects relative increase in share of global wealth of resource-rich and some Asian exporters. The traditional industrial countries will need to accommodate those countries from which major SWFs originate. • International community has a stake in ensuring that SWFs Code of Governance is compatible with global stability; while SWFs have a stake in predictable behavior of the recipient countries. 39 Concluding Remarks • While US may be able to manage the rise of the SWFs, some of the developing countries may feel more vulnerable. All countries, however have little choice but to strengthen their internal data gathering capabilities, and monitoring of FDI and portfolio flows. • The global nature of the financial and capital markets has outpaced the patchwork of financial regulation which is still primarily domestic. • As world financial authority is not on the cards, there is little choice but to rely on committee-based international cooperation and code of conduct (Davies and Green, 2008). 40 Concluding Remarks • The SWFs will also have a political impact. James (2008) has argued that “both the rise of the SWFs and the new importance of big countries as the last backstop of the financial system have changed the way electorates and politicians view globalization. The pendulum is indeed away from the marketplace, which has inherently democratic qualities, and toward big states and big power. And, in many parts of the world that means a new authoritarianism” 41 References • • • • • • • • • • Davies, H. and Green D. (2008), Global Financial Regulations, The Essential Guide. El-Erian, M. (2007), “Foreign Capital Must Not be Blocked”, Financial Times, October 3. IMF (2008), “Sovereign Wealth Funds – A Work Agenda”, Washington DC: IMF, Feb. 29. James, H. (2008), “The Future of Globalization: A Transatlantic Perspective”, Foreign Policy Research Institute [http://www.fpri.org] Johnson, S. (2007), "The Rise of Sovereign Wealth Funds”, Vol. 44, No. 3, Finance and Development, pp. 56-57. Kimmitt, R.M. (2008), “Public Footprints in Private Markets”, Foreign Affairs, 87, 1, pp. 119-130. McKinsey Global Institute (2007), “The New Power Brokers: How Oil, Asia, Hedge Funds, and Private Equity Are Shaping Global Capital Markets”, October. Miracky, W., Dyer, D., Fisher, D., Goldner, T., Lagarde , L. and Piedrahita, V. (2008), Assessing the Risks: The Behaviors of Sovereign Wealth Funds in the Global Economy, New York: Monitor Group. Morgan Stanley (2007), “How Big Could Sovereign Wealth Funds Be by 2015?”, May 3. Nageshwaran, A. (2008), “Risk from Sovereign Funds”, MINT – June 9 2008 42 References • Rachman, G. (2008), “Do not panic over foreign wealth”, Financial Times, April 29, 2008. • Summers, L. (2007), “Sovereign Funds Shake the Logic of Capitalism”, Financial Times, July 30. • Truman, E.M. (2008),“A Blueprint for Sovereign Wealth Fund Best Practices.”, Peterson Institute for International Economics, Washington D.C. , Policy Brief, PB 08/3, April. • Truman, E.M. (2007), “Sovereign Wealth Fund Acquisitions and Other Foreign Government Investments in the United States: Assessing the Economic and National Security Implications”, Testimony before the Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, United States Senate, November 14, 2007. • Tucker, S. (2007), “The Politics of Sovereign Wealth Funds”, Financial Times, September 28. • White G., Davis Bob and Walker, Marcus (2008), “Bear market: Russian wealth funds rattles U.S. and Europe”, The Wall Street Journal, May 8. • Wolf, M. (2007), “We Are Living in a Brave New World of State Capitalism”, Financial Times, October 17. 43