THE AGE OF REFORM

advertisement

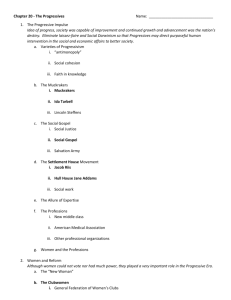

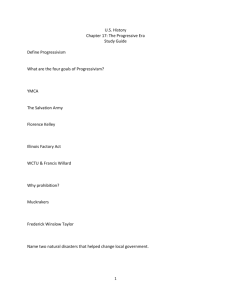

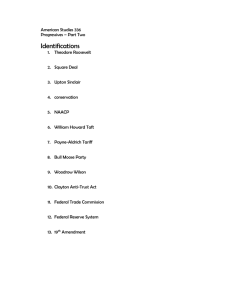

THE AGE OF REFORM • Roots of Progressivism – progressives were never a single unified group seeking a single objective – they sought civil service reform, political reform, government regulation of big business, improvement of conditions in the workplace, and the enactment of antitrust legislation – in response to an increasingly complex society, progressivism represented a “search for order” • The Muckrakers – the popular press published articles on social, economic, and political issues of the day – McClure’s published Ida Tarbell’s critical series on Standard Oil and Lincoln Steffens’s expose on city machines – soon, other editors rushed to adopt McClure’s formula – a veritable army of journalists published stories exposing labor gangsterism, the adulteration of foods and drugs, corruption in college athletics, and prostitution – the degree of sensationalism used by some authors prompted Theodore Roosevelt to label them “muckrakers” • The Progressive Mind – despite its democratic rhetoric, progressivism was paternalistic, moderate, and often softheaded – reformers oversimplified issues and regarded their personal values as absolute standards – progressives came from all walks of life and included great tycoons, small operators, advocates of social justice, prohibitionists, and others – progressivism never truly challenged the fundamental principles of capitalism; nor did it seek to reorganize the basic structures of society – many progressives held anti-immigrant views, and few progressives concerned themselves with the plight of blacks • “Radical” Progressives: The Wave of the Future – influenced by European revolutionary theories, some segments of American society sought radical relief for the ills of industrialism – some labor leaders rejected craft unionism and advocated socialism – in 1905, a coalition of mining and other unions, socialists, and other radicals formed a new union, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) – the openly anticapitalist IWW never attracted the support of mainstream labor – other nonpolitical European ideas influenced progressive intellectuals – few understood, and even fewer read, Freud, but his theories became a popular topic of conversation – some used Freud to argue against conventional standards of sexual morality • Political Reform: Cities First – corrupt political machines ruled many cities – city bosses and machine politics became the primary targets of progressivism – reformers could not defeat the machines without changing urban political structures – new forms included “home rule,” nonpartisan bureaus, city commissioners, and city managers – beyond reforming the political process, progressives hoped to use it to improve society – some experiments at the municipal level included urban renewal, municipalizing public utilities and public transportation systems, and reform of penal institutions • Political Reform: The States – corruption and mismanagement at state level impeded the efforts of municipal reformers – Robert M. La Follette of Wisconsin perhaps best illustrated progressivism in action at the state level – among La Follette’s reforms were the adoption of direct primaries, corrupt practices acts, and laws to limit campaign spending and funding of lobbyists – La Follette also advocated state regulation of the railroads and management of natural resources – other states adopted many elements of the Wisconsin Idea – some states went beyond Wisconsin in making their governments responsive to the popular will with the adoption of the initiative and referendum • State Social Legislation – by the 1890s, many states passed laws regulating conditions in the workplace – these laws restricted child labor, set maximum hours for women and children, and regulated conditions in sweatshops – conservative judges, unwilling to accept an expansion of the states’ coercive power, often struck down such laws on the ground that they violated the “due process” clause of the Fourteenth Amendment – progressives also achieved state legislation regulating the transportation, utilities, banking, and insurance industries – however, piecemeal regulation by the states failed to solve the problems of an increasingly complex society • Political Reform: The Women’s Suffrage Movement – the Progressive Era saw the culmination of the struggle for women’s suffrage – the women’s movement was handicapped by rivalry between the NWSA and the AWSA, by Victorian attitudes about the role of women, and by applications of Darwinian theory – feminists attempted to turn ideas of women’s moral superiority to their advantage in the struggle for voting rights – in doing so, however, they surrendered the principle of equality – in 1890, the two major women’s groups combined to form the National American Women’s Suffrage Association (NAWSA) – the growth of progressivism contributed to the cause of suffrage – after winning the right to vote in several states, NAWSA focused its attention on the national level – the Nineteenth Amendment (1920) granted women the right to vote • Political Reform: Income Taxes and Popular Election of Senators – progressivism also found expression in the Sixteenth Amendment, which authorized a federal income tax, and the Seventeenth Amendment (1913), which provided for direct election of senators – a group of progressive members of Congress also managed to reform the House of Representatives by limiting the power of the Speaker • Theodore Roosevelt: Cowboy in the White House – Roosevelt assumed the presidency following McKinley’s assassination – he brought to the presidency solid political qualifications, a distinguished war record, and credentials as a historian – although the prospect of Roosevelt in the White House alarmed conservatives, he moved slowly and with restraint – his domestic program included some measure of control of large corporations, more power for the Interstate Commerce Commission, and the conservation of natural resources • Roosevelt and Big Business – although Roosevelt won a reputation as a “trustbuster,” he did not believe in breaking up big corporations indiscriminately; he preferred to regulate them – Roosevelt was not an enemy to all large-scale enterprises, merely those that flagrantly seemed to restrain trade – facing a Congress that would not pass strong regulatory laws, Roosevelt resorted to use of the Sherman Act – although his Justice Department brought suit against the Northern Securities Company, the President preferred to reach “gentlemanly agreements” with large trusts – this approach proved successful with U.S. Steel and International Harvester – when Standard Oil reneged on an agreement, however, the Justice Department brought suit • Roosevelt and the Coal Strike – Roosevelt effectively used the powers and prestige of his office to intervene in the anthracite coal strike of 1902 – he attempted to arbitrate between management and the United Mine Workers, but management proved intransigent – the president’s threat to seize and operate the mines convinced the owners of the wisdom of accepting arbitration – neither side was entirely pleased, but, to the American public, the incident seemed to illustrate the progressive spirit and Roosevelt’s “square deal” – Roosevelt’s use of executive power in this case dramatically extended presidential authority and hence that of the federal government • TR’s Triumphs – Roosevelt easily defeated the Democratic candidate, Alton B. Parker, in 1904 – encouraged by his victory and aware of the growing militancy of progressives, the president pressed Congress for passage of the Hepburn Act (1906), which allowed the ICC to inspect the books of railroad companies and to fix maximum rates – it also gave the ICC authority over other interstate carriers and prohibited railroads from issuing passes freely – in response to Upton Sinclair’s novel, The Jungle, which described the filthy conditions in the meat-packing industry, Roosevelt pressed Congress to pass the Pure Food and Drug Act (1907) • Roosevelt Tilts Left – as the progressive impulse advanced, Roosevelt advanced with it – Roosevelt’s approach became increasingly liberal – he placed more than 150 million acres of public lands in federal reserves, strictly enforced usage laws on federal lands, and encouraged state governments actively to regulate their public lands – as Roosevelt moved toward the left, many Old Guard Republicans turned against the president – the Panic of 1907 exacerbated the split – when conservatives blamed him for the panic, Roosevelt responded by moving further toward progressive liberalism; he advocated federal income and inheritance taxes, stricter regulation of interstate corporations, and reforms designed to help industrial workers – when Roosevelt began to criticize the courts, he lost all chance of obtaining further reform legislation • William Howard Taft: The Listless Progressive, or More is Less – Roosevelt’s hand-picked successor, William Howard Taft, garnered the support of Old Guard Republicans as well as progressives and easily defeated William Jennings Bryan – although he enforced the Sherman Act vigorously and signed the Mann-Elkins Act, which expanded the power of the ICC, Taft made a less aggressive president than T.R. had been – Taft was not comfortable with Roosevelt’s sweeping use of executive power – his political ineptness contributed to Taft’s problems – he alienated progressives when he failed to lend full support to a Congressional movement to reform the tariff system – Taft ran afoul of the growing conservation movement in 1910 when he fired the chief forester of the United States, Gifford Pinchot • Breakup of the Republican Party – the Ballinger-Pinchot affair signaled the beginning of a split between Roosevelt and Taft – perhaps inevitably, the Republican party split into factions – Roosevelt sided with the progressives, and Taft threw in his lot with the Old Guard – Taft’s management of antitrust action brought against U.S. Steel in 1911 finalized the split – a portion of the suit was directed against the merger of the Tennessee Coal and Iron Company with U.S. Steel in 1907 – Roosevelt had personally approved of merger and viewed Taft’s action as a personal attack – Roosevelt decided to challenge Taft for the nomination in 1912 – while Roosevelt carried the bulk of the primaries, Taft controlled the party apparatus and secured the nomination – Roosevelt formed the breakaway Progressive party, also known as the “Bull Moose” party, and ran in the general election • The Election of 1912 – the Democrats ran Woodrow Wilson, the reform governor of New Jersey – Wilson’s “New Freedom” promised eradication of special interests and a return to competition – Roosevelt called for a “New Nationalism,” based on regulation of large corporations – hard-core Republicans voted for Taft, but the progressive wing went for Roosevelt – Democrats, both conservative and progressive, voted for Wilson; as a result, Wilson won easily • Wilson: The New Freedom – Wilson quickly established his legislative agenda and successfully steered his legislation through Congress – in 1913, the Underwood Tariff substantially reduced tariffs; a graduated income tax made up for lost revenue – the Federal Reserve Act finally provided the nation with a centralized banking system – Congress created the Federal Trade Commission to regulate unfair trade practices – the Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914 outlawed price discrimination, “tying” agreements, and the creation of interlocking directorates – Wilson’s decisive management style and a Democratic majority in Congress accounted in large part for his successes – Wilson’s progressivism had its limits; he refused to support legislation to provide lowinterest loans to farmers or to exempt unions from antitrust actions – Wilson also declined to push for a federal law prohibiting child labor and refused to back a constitutional amendment granting the vote to women • The Progressives and Minority Rights – a darker side of progressivism manifested itself in the area of race relations – a reactionary on racial matters, Wilson was fairly typical of progressive attitudes; only a handful failed to exhibit prejudice against nonwhite people – most progressives assumed that Native Americans were incapable of assimilating into white society – Asians were subject to intense discrimination – in the South, the Progressive Era witnessed the institutionalization of “Jim Crow” – many progressive women adopted racist arguments in support of the Nineteenth Amendment, while Southern progressives argued for the disenfranchisement of blacks to “purify” the political system – Booker T. Washington and his philosophy of accommodation failed to stem the rising tide of racism, and a number of young and welleducated blacks broke away from his leadership • Black Militancy – W. E. B. Du Bois, the first American black to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard, called upon blacks to reject Washington’s accommodationism – he urged them to take pride in their racial and cultural heritage and demanded that blacks take their rightful place in society without waiting for whites to give it to them – he recognized that environment, not racial factors, caused problems of poverty and crime – Du Bois was not, however, an admirer of the ordinary black American – frankly elitist in approach, Du Bois contended that a “talented tenth” of blacks would lead the way to their race’s success – in 1905, he and other like-minded blacks founded the Niagara Movement – while it failed to attract mass support, it did stir some white consciences – a group comprised largely of white liberals founded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909 – the NAACP was dedicated to the eradication of racial discrimination from American society – the leadership of the NAACP was largely white in its early years, but Du Bois became a national officer and editor of the organization’s journal – more important, after the founding of the NAACP, virtually every leader in the struggle for racial equality rejected Washington’s approach