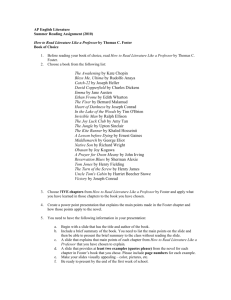

File - Education Reach for Texans

advertisement

Perspectives of Foster Care Youth and Parents on Challenges of Straight and LGBTQ Youth Transitioning to Young Adulthood: Lessons for Higher Education MARIA SCANNAPIECO, PH.D. C E N T E R F O R C H I L D W E L FA R E U N I V E R S I T Y O F T E X A S AT A R L I N G T O N M S C A N N A P I E C O @ U TA . E D U H T T P : / / W W W 2 . U TA . E D U . / S S W / C H I L D W E L F. H T M K I R S T I N PA I N T E R , P H . D , L C S W S E N I O R D I R E C T O R , M H M R TA R R A N T C O U N T Y K PA I N T E R @ U TA . E D U Presentation Outline Overview Review of Empirical Literature LGBTQ All Youth Aging Out of Foster Care Foster Youth and Higher Education Examples of Programs Discussion and Conclusion Overview Overview Teenagers make up about 34% of all foster care youth Of children in foster care, 55% are African American or Hispanic, 52% are male, and the median age is roughly 9 years Overview About 30,000 adolescents exited foster care in 2010 because they reach eighteen years of age* 30% of these youth have been in care for over 9 years without a permanent placement (DHHS, 2011) Children who have spent a significant time (at least one year) in foster care between ages 13 and 18 are likely to be seriously affected by the experience in ways that create barriers to their further social inclusion and participation (Wolanin, 2011) Overview Overall, the number of children in foster care has dropped 8% in one year and 20% in the past decade Recent federal policy supports this trend • Fostering Connections to Success and Increasing Adoptions Act of 2008 allows states to claim federal funds to assist children who are cared for by relatives other than their parents Overview Though the trend is promising, challenges still exist The number of foster youths aging out of the system has increased over the past decade • • • Nearly 30,000 youths aged out of foster care without a permanent family in 2010, compared to 19,000 youths who aged out in 1999 Percentage of all exits from foster care due to emancipation increased from approximately 7 % in 2000 to about 10% more recently Many of these foster care alumni have to face problems of poverty, lack of health care, limited education, unemployment, homelessness, criminal justice system involvement, and teen pregnancy without the support of permanent families (www.childrensdefence.org 2010) Review of the Research GLBTQ Youth In General Population GLBTQ Youth are…. 7 times more likely to be victims of hate crimes. 5 times more likely to commit suicide than heterosexual youth and account for 30-40% of all teen suicides. 3 times more likely to be targeted by homophobic abuse in school than youth of color or women. GLBTQ foster youth are…..the facts 25-40% of homeless youth are gay, lesbian, or bisexual. Housing instability impacts LGBTQ foster youth health: disruptions to continuity to medical care; unaddressed dental check-ups. Where as approximately 5-10% of the general population is gay or lesbian, a conservative, although staggering disproportionate estimate of 20% youth in out-of-home care are gay or lesbian. 50% suffer homophobic abuse in their biological home. 28% are forced to leave their biological homes. Over 50% of youth-serving organizations/agencies report not having , or the lack of, materials to be prepared to serve GLBT(Q) youth. How LGBTQ Youth Enter The Foster Care System Because of homophobia and transphobia in their homes, schools, and social settings, LGBTQ youth enter the foster care system at a disproportionate rate. Many LGBTQ youth face neglect or abuse from their families of origin because of their sexual orientation or gender identity. A recent study found that over 30% of LGBT youth reported suffering physical violence at the hands of a family member after coming out. Because of lack of acceptance and abuse many LGBTQ youth are removed from their homes or found to be "throwaways" by child protection agencies and placed in the foster care system. How LGBTQ Youth Enter The Foster Care System According to another recent study, 20% percent of LGBTQ youth reported skipping school each month because of fear for their own safety. And another study found that 28% of LGBTQ youth dropped out of school due to peer harassment. As a result of lack of acceptance and abuse in the home and at school, a disproportionate number of youth living on the streets are LGBTQ. The National Network of Runaway and Youth Services estimates that between 20-40% of homeless youth are LGBTQ. Challenges faced by LGBTQ youth in foster care Barriers between caseworkers and LGBTQ youth - a lack of trust in caseworkers and foster care system; - staff miscomprehending LGBTQ needs; - unaddressed cross-cultural disparities; Review of the Empirical Literature on Youth Aging Out of Care Youth aging out of foster care have significant difficulties transitioning into independent living and /or higher education. 31% of the former foster youth live with a relative; those who live independently are 37% Adverse Childhood Experiences (Trauma) Review of the Empirical Literature on Youth Aging Out of Care Research indicates that children "lose an average of four to six months of educational attainment each time they change schools." 65 % of foster care youths experienced seven or more school changes from elementary school through high school. Changing schools frequently reinforces a cycle of emotional trauma of abandonment and repeated separations from adults and friends. Empirical Literature Some of the research findings of the effects of youth who have entered the foster care system are: Youth in foster care tend to be behind educationally compared to their peers, with as few as 33% graduating from high school at time of aging out to 50 %. The national high school dropout rate in the US ranges between 5% and 11% Empirical Literature In comparison to the general youth population, fewer foster care adolescents are regularly employed Fewer than half have jobs at the time of discharge Former foster care youths are twice as likely not to have enough money to pay their rent, and one-quarter are categorized as food insecure on a composite measure of food security Empirical literature Higher proportions of youth who have been in foster care receive public aid A study found that 30% of foster care youths experienced serious health problems after leaving foster care. Fiftyfive of the participants had no health insurance. Of those with health coverage: 25% were on Medicaid, 11% on another form of public assistance, and only 9% had obtained private health insurance. Empirical Literature Forty-seven percent of the adolescents in care had a disabling condition and 37 percent were clinically diagnosed as emotionally disturbed following discharge from foster care Much higher than the 12 to 15 percent estimate for the general youth population. Youth living with foster parents are more likely than children living with biological parents to have behavioral and emotional problems, problems in school adjustment, and to be in poor physical and mental health Empirical Literature A higher proportion of former foster care youth have also been found in the criminal justice system Former foster care youths are more likely than their peers to raise children out-of-wedlock. More than 60 percent of females leaving the system have a baby within four years, almost always outside of marriage Empirical findings One study found that 45% of former foster care youth had "trouble with the law" after exiting the foster care system: 41% spent time in jail, and 26% were formally charged with criminal activity. 37% of the youths experienced one or more negative outcomes, including victimization, sexual assault, incarceration, or homelessness. A study found that "13 % of the female participants reported having been sexually assaulted and/or raped within twelve to eighteen months of discharge from care." Foster Youth and Higher Education Statistics at a glance… Dworksky & Courtney (2010) report that foster youth approaching adulthood have the same aspirations for higher education as do youth in the general population. A majority of foster youth want to attend college and anticipate they will achieve a college degree (Courtney, et al., 2004). Approximately 58% of youth who age out of foster care will have a high school degree at age 19, compared to 87% of non foster youth (The Pew Charitable Trusts, 2007) About 3% of foster youth who age out of care will have a college degree at age 25, compared to 28% of the general population (The Pew Charitable Trusts, 2007). Foster Youth and Higher Education The gap between rate of college attendance for foster youth and their peers is higher than the gap between high school completion for foster youth and their peers (The Institute for Higher Education Policy, 2005). This suggests that the transition to higher education is more challenging than the completion of high school. Foster youth may not have the skill, maturity, or necessary support to access higher education. Fragmentary data suggests that among foster youth who do attend college, the attrition rate is very high (The Institute for Higher Education Policy, 2005). Dworksy and Courtney (2010) state that rates of college graduation among former foster youth are estimated to be between 1% and 11%, but data collection is somewhat faulty. Foster Youth and Higher Education A reason why foster youth do not apply to college is that they are not aware of the college opportunities available to them, and they do not have the practical knowledge and skills to successfully navigate the complex college application process. In addition to the difficulties foster youth have in connecting with the college admissions and student financial aid processes, the programs that exist to help them are often inadequate to meet their needs (i.e. federal TRIO programs (Talent Search, Upward Bound, and Educational opportunity centers) and GEAR UP (Gaining Early Awareness and Readiness Undergraduate Program)). Recommendations A need for a universal safety net of guaranteed services such as healthcare, tuition, housing, and employment assistance (Atkinson, 2008). Dworsky and Courtney (2010) recommend eliminating “arbitrary” deadlines (p.7) for removing support to youth because they turn 18 or 21. Many parents provide emotional and financial support to their children well into adulthood. In Illinois, youth whose foster care benefits were extended to age 21 were more likely to be enrolled in college at the age of 21 than 21 year old foster youth in neighboring states. Former foster youth may simply take longer to complete their educations because they have remedial academic work to do. They may also be hindered by financial and life barriers, including supporting their own children. Programs targeted to former foster youth on college campuses that provide financial, academic and emotional support. Recommendations The Research and Planning Group for California Community Colleges (2008) recommends that institutions take a case management approach with former foster youth, linking them with one individual who can help identify needs and broker other services and supports. Other recommendations include – Partnerships between community colleges and departments of social services to access ILPs and funds (like ETVs); Securing dedicated slots for transitional housing (Dworksy & Courtney, 2010, also note that housing is a critical need among former foster youth in college); Establishing business relationships with private and corporate sponsors to maximize donations; Developing a tracking system that allows the institution to monitor outcomes. Recommendations Mandelbaum (2010) suggests a model of community education as a way of transferring knowledge and information through collaborative relationships between undergraduate and graduate students, academics, professionals, community organizers and foster youth students. The model promote and encourage public awareness, community engagement, and advocacy. Recommendations National Community Education Association has concluded that an effective community education project should involve the community, use resources efficiently, and encourage and promote lifelong learning, selfdetermination, and self-help. Higher Education Programs Generally speaking, campus programs supporting former foster youth include: Some programs also match former foster youth with mentors – either faculty members, other college students, or former foster youth alumni of the school (Austin Community College’s program includes mentoring). Care packages (school supplies, suitcases, and other essentials) Support groups Emergency funds Provide leadership trainings Helpful websites that organize information about financial aid (including ETVs) in one place. These programs often rely on private donations and corporate sponsorship. Communicate through partnerships Higher Education Programs Of note is Virginia Community Colleges “Great Expectations Program, “ which encompasses the elements noted above. Interestingly, the program serves foster youth/former foster youth ages 13 to 24, reaching the population across a broad span of developmental milestones. About Great Expectations Serves foster youth 13 – 24, in both high school and college. Focuses on the value of a college education as the best way to gain employment and achieve independence. Provides education and employment opportunities that will improve the likelihood of success for foster youth. Offers individual support for at-risk foster teens as they finish high school, leave their foster homes and transition to postsecondary education and living on their own. About Great Expectations Launched in 2008 at 5 Virginia Community Colleges. Now offered at 15 of the 23 community colleges; 2 additional colleges joining in 2012. • • • • • • • • Danville Germanna J. Sargeant Reynolds John Tyler Lord Fairfax Mountain Empire New River Northern Virginia • Patrick Henry Piedmont Virginia Southside Virginia Southwest Virginia Tidewater Virginia Highlands • Wytheville • • • • • Great Expectations Services Help with the college admissions/financial aid Resource Center www.GreatExpectations.vccs.edu Personal counseling and individual tutoring Career exploration and coaching; job preparation Mentoring (by college staff, college peers and community volunteers) Special programs, e.g. life skills, healthy relationships Emergency and incentive Funds Online Best Practices Forum Starting a New Program Essentials Challenges Support of the college’s admin. Part-time Campus Coaches Special training for Campus Recruiting students in rural areas Coaches Coordination with other depts. Building awareness of the (e.g. financial aid, student success, counseling, tutoring) Special programs Emergency funds program in the community Setting boundaries Lack of housing Transportation Cultural competence It Takes a Team! The Great Expectations Campus Coaches are the key! Coaches are…..the go-to person who musters the other services available on the campus and in the community for the students The team includes….the high school career coaches, DSS workers foster and adoptive parents, volunteer mentors interns and work/study students, community supporters Four Year Colleges Ball State University and Ivy Tech Community College http://cms.bsu.edu/Academics/CentersandInstitutes/SSRC/GuardianScholars.aspx California Polytechnic University, Pomona http://dsa.csupomona.edu/rs/ California State University, Fullerton www.fullerton.edu/guardianscholars Colorado State University www.today.colostate.edu/story.aspx?id=4999 Miami University Regionals www.regionals.muohio.edu/fostercare/ Middle Tennessee State University www.mtsu.edu/nextstep/ Northern Arizona University www4.nau.edu/insidenau/bumps/2010/8_27_10/blavins.html Ohio University www.ohio.edu/univcollege/fostercare/ Sam Houston State University www.shsu.edu/~forward/ San Francisco State University www.sfsu.edu/~eop/gs.html San Jose State University www.sjsu.edu/cmesociety Community Colleges California Community College Chancellor’s Office | Foster Youth Success Initiative (FYSI) www.cccco.edu/searchresults/tabid/137/default.aspx?search=FYSI Austin Community College www.austincc.edu/fca City College of San Francisco www.ccsf.edu/NEW/en/student-services/studentcounseling/guardians-scholars-program.html Erie Community College Independence bound http://www.ecc.edu/academics/specialprograms/independencebound Fullerton College http://fosteryouth.fullcoll.edu/ Los Angeles City College www.lacitycollege.edu/services/guardianscholars/ Seattle Central Community College www.seattlecentral.org/collegesuccess/index.php Tallahassee Community College www.tcc.fl.edu/about_tcc/student_affairs/departments/enrollment_services_and_stu dent_success/i_am_a/foster_youth/fostering_achievement_fellowship_program Other Programs and Initiatives of Note Guardian Scholars at Hunter College, John Jay College and Kingsborough Community College. http://newyorkersforchildren.org/category/programs/ The Eagle County Continuing Education Community Collaborative’ s Guardian Scholars Program www.theyouthfoundation.org/programs/GuardianScholar.html Graham Windham’s Scholars Program www.alisteducation.com/info/grahamwindham-program Washington State’s Governors’ Scholarship Program for Foster Youth www.collegesuccessfoundation.org/Page.aspx?pid=417 Articles written by foster youth http://www.representmag.org/topics/college.html Guardian Scholars programs http://www.orangewoodfoundation.org/programs_scholars.asp