15 Review Essay Moraru Edited

advertisement

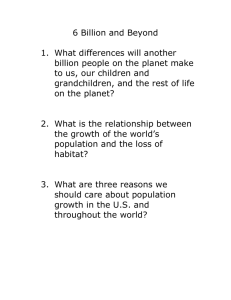

<brk>Ursula K. Heise, Sense of Place and Sense of Planet: The Environmental Imagination of the Global</> <bkf>New York: Oxford University Press, 2008, 250 pp.</> Although risky business, prophecies are nonetheless tempting. So here is one: looking back on the past two decades, the literary-cultural historians of the future—a future not too remote from us, I would think—will in all likelihood see those years as a sort of epistemological intermezzo, a moment of transition from one paradigm to another across the humanities, inside and outside the U.S. It seems to me that a gradual shift has been underway in the human sciences over the last twenty-five years. Concomitant and analogous to recent reorientations in literature, the arts, and geopolitical arrangements, this shift has touched off the progressive albeit uneven legitimizing and academic-intellectual institutionalization of something that might be viewed as a new episteme, a new way of looking at the surrounding world and of producing knowledge about this world. A good number of influential voices in theory, criticism, and cultural studies, in comparative analysis (especially in “new comparatism”), in philosophy (chiefly in ethics), in psychoanalysis (primarily among the “Champ lacanien” group members), in political science, economics, sociology (principally in risk sociology), and in geography have been in the avantgarde of this sea change, having variously anticipated it from the beginning of their careers (Jean-Luc Nancy, Sylviane Agacinski, Guy Scarpetta, Paul Gilroy, Marc C. Taylor, David Hollinger). Others joined this transformative trend a bit later (Jacques Derrida, Tzvetan Todorov, Jürgen Habermas, Julia Kristeva) as they turned to cosmopolitan, “postnational,” global, planetary, and “other” (“alterity”-focused) questions years prior to the historical watershed of this transitional interval, the official end of the Cold War. Similarly, many scholars have been associated with older directions such as postmodernism (Jean Baudrillard), postcolonialism (Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Homi Bhabha, K. Anthony Appiah), poststructuralism, and deconstruction (Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, J. Hillis Miller). Still others took the lead right before and after 1989 in fields such as comparative and translation scholarship (Henry Sussman, Timothy J. Reiss, Eugene Eoyang, Rey Chow, Yunte Huang, Zhang Longxi, Emily Apter, Lawrence Venuti, Michael Cronin); cosmopolitanism, world governance, sovereignty, and human rights (Bruce Robbins, Pheng Cheah, Danilo Zolo, Derek Heater, Seyla Benhabib, Will Kymlicka, Daniele Archibugi, José María Rosales, María José Fariñas Dulce, Timothy Brennan, Amanda Anderson, Kok-Chor Tan, Volker Heins, Camilla Fojas, and many more); “cosmocultural,” “geocritical,” “ecocritical,” and “planetary” analysis (Franco Moretti, Yi-Fu Tuan, Gérard Raulet, Bertrand Westphal, Wai Chee Dimock, Lawrence Buell); global, worldsystem, “network society,” and “empire” studies of various persuasions and foci (Manuel Castells, Arjun Appadurai, Alexander R. Galloway and Eugene Thacker, Steven Shaviro, Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Amy Kaplan, Roland Robertson, Martin Albrow, David Held, Frederick Buell). Further, some of these are, I suspect, relatively comfortable with the disciplinary tags usually attached to their interventions: Ulrich Beck and Jacques Demorgon (sociology), Peter Singer and Appiah again (ethics). Others, such as Slavoj Žižek, Alain Badiou, and Georgio Agamben, await, perhaps in vain, classifications less nebulous than “philosophy.” Additionally, critics like Charles Taylor, Hollinger, Werner Sollors, Benedict Anderson, Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Charles Johnson, Stuart Hall, Aiwa Ong, John Carlos Rowe, James Clifford, and Giles Gunn, who broke new ground in race, ethnicity, citizenship, community, ethnography, and multicultural studies ten or twenty years ago, in hindsight appear even more forward- looking. Finally, issues such as those intensely addressed by virtually all of the above have rekindled interest in a number of classics, ancient and modern, in philosophy (Stoicism, Spinoza, Husserl, Buber, Levinas), hermeneutics (Gadamer and Ricoeur), psychoanalysis (Lacan), sociology (Tönnies and Simmel), the history of ideas and ideologies (Benda and, more recently, George Steiner, Stephen Toulmin, and Peter Coulmas), anthropology (Clifford Geertz), literarycultural and discourse studies (Bakhtin), justice theory (Rawls and his “law of people”), history and political economy (Immanuel Wallerstein and, via his work, Braudel and the Annales). Such wide-ranging scholarship revolves systematically and characteristically around the concept of connectedness, of being in, and thus being culturally-ontologically shaped and explained by, the relation with others and the elsewhere. We exist in the world, and the global positioning and the imbrications derived from it matter existentially and hermeneutically more than ever before. Relatedness is thus the epistemological keystone and critical operator in this fast advancing, epoch-making reflection field, a field or fields to which Ursula K. Heise’s second book belongs even more than her 1997 Cambridge volume, Chronoschisms: Time, Narrative, and Postmodernism. Otherwise, the 2008 Oxford monograph can be said to be the previous title’s companion in that it gives us, with stylistic elegance and superb command of the material at hand, a “sense of place” while the other sought to capture a “sense of time.” The latter was our postmodern time, but Chronoschisms also pointed convincingly to a “post-historical” direction within the panoply of postmodern temporal vectors, gesturing toward a certain insufficiency and cultural-historical obsolescence of critical chronographies too much beholden to “local time.” Not necessarily popular with mainstream postmodern and postcolonial theorists, that move proved beneficial, however, for the scholarly groundbreaking and intellectually robust argument made by Sense of Place and Sense of Planet regarding the turn-of-the-millennium “environmental imagination.” Painstakingly developed throughout a book no less sensitive to details, ambiguities, and their tricky implications in literature, culture, and theory, this argument is couched in a more radical form in the discussion of “deterritorialization” from Part I’s second chapter. “In the context of rapidly increasing connections around the globe,” Heise contends, “what is crucial for ecological awareness and environmental ethics is arguably not so much a sense of place as a sense of planet—a sense of how political, economic, technological, social, cultural, and ecological networks shape daily routines” (55). Since few people have a better grasp than Heise of the sinuous history of environmental thought on either side of the Atlantic, we should pay attention when she insists that “Advocacies of the local can play a useful political and cultural role in one context and become a philosophical as well as a pragmatic stumbling block in another” (59). All in all, the priority of the moment seems to be “to reorient current U.S. environmental discourse, ecocriticism included, toward a more nuanced understanding of how both local cultural and ecological systems are imbricated in global ones” (59). In turn, Heise’s case for “an increased emphasis on a sense of the planet, a cognitive understanding and affective attachment to the global,” should be taken “not as a claim that environmentalism should welcome globalization in every form (there are good reasons to resist some of its dimensions) or as a refusal to acknowledge that appeals to indigenous traditions, local knowledge, or national law are in some cases appropriate and effective strategies. Rather, it is intended as a call to ground any such discourses in a thorough cultural and scientific understanding of the global— that is, an environmentally oriented cosmopolitanism or ‘world environmental citizenship,’ as Patrick Hayden calls it” (59). As implied here and explained elsewhere in greater detail, Heise’s intervention positions itself at the crossroads of planet-minded/world-systemic ecocriticism, globalism and “new” cosmopolitan studies, as well as risk sociology in the Beck-Giddens line. In fact, she calls her critical model eco-cosmopolitanism, and for good reason. Beck, Giddens, and some recent ecocritics have also framed their analyses in explicitly cosmopolitan terms, which terms—and this needs to be said—have also been reframed so as to deter associations with the Western, elitist, “jet-setting” traditions, old and new, of cosmopolitan thought. Countless critics of cosmopolitanism (most of them of orthodox-Marxist and postcolonial persuasion) have charged traditional, rationalist-humanist cosmopolitan thinking with (barely disguised) parochialism; the cosmopolitan, they claim, is a local (Western) extrapolation. Fair enough, we may reply, but, as Heise shows time and again, many advocates of anti-globalization, postcolonial, and regionalist“grassroots” environmentalist resistance fall into the trap of the same localism. As she demonstrates, this self-described resistance is both impractical in a world of all-pervasive connectivity and implausible philosophically. And yet, she is also right in that this sort of reaction has led to a veritable dead end in global studies. What Heise proposes instead is a strategic, planetary refocusing of the whole discussion, one which would allow us to make sense of place and our role within it against the backdrop of the planet’s “bigger picture.” Should we do so, both individuals and groups, cultures, ethno-racial communities, and statal-regional formations from homelands and nations to empires may reveal themselves to us in the final analysis as outcomes of frequently older and vaster flows, exchanges, and amalgamations. Quintessentially comparative, ever sensitive to context, to the meaningful beyond of the hic et nunc and the seemingly discreet, this macroanalysis yields remarkable results when applied to specific cases. The book generally focuses on post-1960s accounts of the environment in literature (mainly fiction), the arts (including film), and theory (philosophy, ethics, sociology, ecocriticism, and so forth) in American, British, and German cultures, in particular on those projections that attest to an emerging “environmental imagination of the global.” This notion, this imagination or, as I prefer to call it, “imaginary,” and ultimately Heise’s whole argument are perhaps more easily grasped if we merely permute the terms. What she illuminates with unprecedented insight and effectiveness is, indeed, a global imagination of the environment—an imagination of the writers and artists under scrutiny but also of the critic herself. This inquiring imagination time and again uncovers and steps over the limits and limitations of the local, especially of the nation-state, which shortcomings become even more obvious when it comes to addressing environmental issues, whether those issues are behavioral (how we affect nature), intellectual (how we understand our surroundings), or ethical (what is to be done). Heise’s work blends theory, cultural-historical background, and interpretations of specific texts, poems, paintings, and movies evenly, but overall the first sixty pages or so (the introduction and chapter 1) are more theoretical than the rest, except chapter 4 of part II, which offers the most competent and judicious treatment of risk theory I have ever read. Part I is titled “World Wide Webs: Imagining the Planet,” and part II, “Planet at Risk,” but the terms could easily swap places, and Beck would surely agree that recent literature, art, and criticism—his own no less—bear witness not only to a Weltrisikogesellschaft (world risk society) but also to a germane, risk-grounded imagination. The environmental imagination does articulate a risk imaginary, even though, as Heise underscores in her glosses to John Brunner’s and David Brin’s visions of an overcrowded planet (part I, chapter 2), this occurs less in the apocalyptic terms of 1960s demographic dystopias while both the risk notion itself and the images bodying it forth are increasingly global in scope. Today’s risks globalize in that most of them are global in scope and impact us all. In order to evaluate these concerns properly—let alone do something about them— the people of the world/globe must come together. Before anything else, though, we must rethink one of our most basic “habituses,” as Bourdieu would say—we must re-imagine place and related spatial notions and predispositions as placed in a world of interacting places and thus step beyond a certain isolationist, disconnected environmentalism. It is not so much that the latter disregards the global, as Heise observes in Part I. Rather, the concern remains that the global is uncritically seen as a supplement to permenently existing, “natural,” and “rooted” places and their local communities and cultures. Therefore, what we need to re-conceptualize in the wake of developments both worldly (socioeconomic and geocultural) and theoretical is the dynamic of the local and global. In this project, it may well be that writers such as Don DeLillo and Richard Powers are ahead of the game. Dealt with in Part II, chapter 5, White Noise and Gain bear out (albeit in slightly different ways) a contextualist perception of “events” that reframes local and natural occurrences in supralocal and techno-cultural terms that, to my mind, remain unrivaled analytically to this day. So does to some degree Lothar Baumgarten’s strikingly original movie Der Ursprung der Nacht (Amazonas-Kosmos) (The Origin of the Night: Amazon Cosmos [or, the Cosmic Amazon]). The film was not shot in the Amazonasgebiet but in the Ruhrgebiet, with the Rhein as an Amazonian stand-in! A cinematic farce? Far more than that, Heise argues in the last chapter of Part I (“Adventures in the Global Amazon”). As she explains, not only does Baumgarten deploy a whole performative-theoretical apparatus to translate into the language of foreign places what at first blush seems eminently idiomatic (localist); he also gives us an insight into the extent to which the environmental plight of precisely “located” biocultural configurations is in all actuality unbounded, part and parcel of larger ensembles of similar, communicating, and overlapping ecosystems plagued by comparable if not identical problems. As a network world, Heise observes throughout, this universe is best and “isomorphically” represented by a literature where collage, intertextuality, and other forms of textual “contagion” (and contiguity) take pride of place in the repertoire of discourse. I said “form,” but this is hardly a formal matter since form is representation and representation is also interpretation, a critical reconstruction. Nor is, to be sure, Heise a formalist. But it is very refreshing to discover, in a critical work whose stakes reach far higher than the stylistic and the literary, how much attention she pays to aspects of style and technique. The best book I have read in a while in the fast evolving fields of comparative studies, globalization, cosmopolitanism, ecocriticism, and (post-?)postmodernism, Sense of Place and Sense of Planet is and—to offer a final prophecy—will remain a classic for years to come. <rau>Christian Moraru <#> University of North Carolina, Greensboro</rau> <***>