CFT

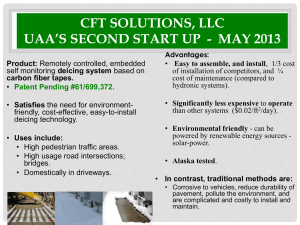

advertisement

The Impact of Counterfactual Thinking on Persuasion K A I - YU WA N G , P H. D. G OODMA N S CHOOL OF BUS I N ESS, BROCK UN I V ERSITY, CAN ADA N AT IONA L UN I V E RSITY OF K AOHS I U N G, M A RCH 1 3 , 2 0 1 4 What is Counterfactual Thinking? oCounterfactual thinking (CFT) - a mental process that simulates possible routes or measures to negate what has happened. o “if only I had chosen that number, I would have been a millionaire now” o“if only I had taken a different route to the airport the other day, I would have not been caught in the traffic, missed my flight, and wasted one day time at the airport.” oCounterfactual thoughts can account up to 12% of all the thoughts occurred to our mind on a daily base (Summerville & Roese, 2008). What is Counterfactual Thinking? Content Upward: Generate alternatives that are better than actuality (could have made things better). If only I wake up earlier, I would not get in the traffic jam. Downward: Generate alternatives that are worse than actuality (things could have been worse). At least I still get a seat in the next flight. Structure Additive: Thoughts in which people wish they could add an action to reality. If only I had set the alarm, I would not oversleep. Subtractive: Thoughts in which people wish they could remove an action from reality. If only I had not come home late last night, I would not oversleep. 4 If only I had purchased a TV with an extended warranty, I would not have to spend so much money on this repair. --Upward counterfacutals At least, I did not purchase the model with the longer warranty and smaller screen, because I enjoy my large screen TV. --Downward counterfactuals 5 If only I had purchased the SONY TV, I would have enjoyed the excellent customer service. --Additive counterfacutals If only I have not purchased the Toshiba TV, I would not now bear with the poor customer service. --Subtractive counterfactuals 6 CFT Research Papers Wang, K., Liang, M. and Peracchio, L. Strategies to Offset Dissatisfactory Product Performance: The Role of Post-purchase Marketing, Journal of Business Research. Volume 64, Number 8, August, 2011. Wang, K., Yang, X. and Jain, S. Negative Consumption Episodes, Counterfactuals and Persuasion - Association for Consumer Research Annual Conference, Vancouver, British Columbia, October, 2012. Wang, K. and Zhao, G. Counterfactual Thinking and Consumers’ Preference for Product Feasibility - American Marketing Association Winter Marketing Educators’ Conference, Orlando, Florida, February, 2014. Wang, K., Bublitz, M. and Zhao, G. Counterfactual Thinking and Consumers’ Health Choices and Behaviors- working paper, 2014. The Impact of Counterfactual Thinking on Postpurchase Evaluation K A I - YU WA N G , BROCK U N I V ERSITY, CA N A DA M I N L I L I A N G, S U N Y - BROCK PORT L AUR A A . P E R ACCHIO, U N I V ERSI TY OF W I S CONSIN - MI LWAU K EE 8 9 Introduction “There is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.” Shakespeare Focus of Research • Examine how CFT influences people’s product evaluations after a satisfying or dissatisfying purchase experience. • Explain the process underlying the formation of evaluations. 10 Research Questions How and when does CFT influence consumers’ product evaluations after experiencing product satisfaction or dissatisfaction? Does motivation provide a potential boundary condition for the negative cycle of upward CFT? What is the process underlying the formation of product evaluations? 11 CFT and Outcome Valence Positive outcome: more downward counterfactuals + greater satisfaction Negative outcome: more upward counterfactuals + greater dissatisfaction. (Roese, Sanna, and Galinsky, 2005; Schwarz and Bless, 1992; Markman et al., 1999) downward counterfactuals upward counterfactuals The latter situation could turn out a negative cycle. 12 The Moderating Role of Motivation Upward CFT might be inhibited in order to change negative affect, but only when people have more ability or resources to overcome upward CFT and engage in downward CFT (Roese et al. 2005; Taylor 1991). Motivation/NFC Positive outcomes do not motivate people to expend cognitive effort processing information unless called for by other goals (Schwarz 1990; Bless, Bohner, Schwarz, and Strack 1990). 13 Overview of Two Studies oStudy 1 investigates whether higher motivation can break the reciprocal cycle of upward CFT when people encounter a negative purchase outcome and explores the effects that underlie this process. oStudy 2 provides an extension of study 1 and establishes the robustness of the documented findings. A follow-up customer survey replaced the CFT instruction to induce participants to engage in CFT. 14 Study 1: Method Participants: 113 students Procedure • Each was randomly distributed a survey booklet. • First viewed one of the two versions of computer purchase scenarios. • Each was provided with one of the two instruction sets • Completed NFC items. • Evaluated the Product (not useful/useful, unappealing/appealing, not easy to use/easy to use, not excellent value/excellent value, and not a worthwhile purchase/a worthwhile purchase). • Wrote down thoughts that occurred to them during the purchase experience. 15 Product Evaluation: Purchase Outcome x Thinking Instruction x NFC 6 5.43 5.23 5 5.28 5.06 4 3 Negative Outcome No CFT instruction CFT instruction Product Evaluation Product Evaluation Positive Outcome CFT instruction 6 5 4 No CFT instruction 4.60 * 4.27 * 5.10 3.54 3 Low NFC High NFC Low NFC High NFC 16 Study 2: Overview Contribution: •Replicate study 1 and further explore the process that underlies these effects. Purpose: • Bring research into a more naturalistic marketing context. • Investigate whether a follow-up customer survey can induce customers to think counterfactually. Research Design: 2 x 2 •Thinking Instruction: follow-up survey vs. no follow-up survey •Motivation: high vs. low Dependent variables: Product evaluations and Thoughts 17 Motivation High-processing-motivation condition • Participants were informed that they were part of a small group of people participating in the study. Their opinions were extremely important to the company represented in the survey. Low-processing-motivation condition • They were told that they were among a large number of students at many universities. Their opinions might be used after aggregating them with those of other students. (Chaiken and Maheswaran 1994; Peracchio and Meyers-Levy 1997) 18 Study 2: Method Participants: 54 students Procedure • Similar to the procedure in study 1. Study 2 differed from study 1 in three ways: • Only the negative-outcome purchase scenario was employed. • The CFT instruction was replaced with a follow-up customer survey. • Respondents’ processing extensiveness (motivation) was manipulated following a procedure used in previous research (Chaiken and Maheswaran 1994; Peracchio and Meyers-Levy 1997). 19 Product Evaluation: Thinking Instruction x Motivation Product Evaluation * No Follow-up Survey Follow-up Survey 5 4.41 * 4.49 4 3.90 * 3.71 3 Low Motivation High Motivation 20 Contributions and Applications Theoretical contributions • Provide evidence that cognitive ability and resources –NFC and motivation— impact the direction of CFT. • Explore the impact of counterfactual thinking on product evaluation. • Explain the process underlying the formation of product evaluations. Managerial applications • Comment cards and satisfaction surveys • Service/product failure recovery 21 Counterfactual Thinking and Consumers’ Preference for Product Feasibility KAI-YU WANG, BROCK UNIVERSITY, CANADA GUANGZHI ZHAO, LOYOLA UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND, USA Introduction oFocus of Research oExamine how CFT might activate a process- (vs. outcome-) focused mindset and influences product choice preference for product attributes (feasibility vs. desirability) following a negative consumption episode in a related/unrelated domain. oExplain the underlying mechanism of the observed effects. CFT Literature Review oImmediate emotional consequences oRegret or happy, depending of the direction of CFT (Markman et al., 1993; Rajagopal et al., 2006). oDownward CFT can make individual feel rejoiced; whereas upward CFT make individuals feel regretful. oDecision-making and behavior oAnticipated counterfactuals: house insurance purchase (Hetts et al., 2000) oAnticipated regret and responsibility: brand and price (Simonson, 1992) CFT Literature Review oCognitive implications oPrime or activate certain information-processing styles. oFollowing a negative consumption experience CFT can make consumers more cautious in buying a replacement product (Krishnamurthy & Sivaraman, 2002). oContent-neutral CFT influences: CFT can alter or prime certain cognitive mentality and information-processing styles that influence individuals’ behavior in a domain or context that is detached from and independent of the original CFT experience. CFT Literature Review oTwo common dimensions to differentiate CFT (Gleicher et al. 1990; Nan, 2008; Roese & Olson, 1993) oContent: upward vs. downward oStructure: additive vs. subtractive oUpward CFTs are common in consumption context and are especially like to occur when consumers experience negative consumption outcome (e.g., product failure) (Roese, Sanna, & Galinsky, 2005; Wang et al., 2010). oBoth additive counterfactuals and subtractive counterfactuals are likely in consumption context. oCFT essentially involves mental simulations of the process of following certain sequences of action, taking certain behavior courses/routs/paths, and performing certain actions to negate a reality. CFT Literature Review oProcess-related mental activities: oentails individuals to re-live how an incident happened, figure out which steps went wrong, and ofinally come up the necessary steps or alternative courses to negate the incident. Recall the process… Simulate alternatives… CFT Literature Review oPriming certain process-focused cognitive mindsets: oPrime a relational processing style which subsequently makes individuals focus more on relationships and associations between stimuli and boosts individuals’ creativity (Kray et al., 2006). oProblem-solving process CFT on product failure (e.g., failed electricity surge protectors) can lead consumers to extend extra effort to scrutinize claims made about surge protectors in ads and process ad information (Krishnamurthy & Sivaraman, 2002). CFT Literature Review oTwo basic routes through which CFT influences individuals (Epstude & Roese, 2008): ocontent-specific route: Product failed due to an electricity surge Scrutinize surge protector ad information ocontent-neutral route Missing flight Buy a book and order a meal in the airport Product Feasibility and Desirability oProduct feasibility: how easily to operate the product (Goodman & Malkoc, 2012). o(Computer software) Smaller file size, less time to download oProduct desirability: the value of owning the product. o(Computer software) Higher product quality rating, a complete set of features oFeasibility is negatively, but desirability positively, related to the number of product beneficial features (Thompson, et al., 2005). Feasibility or Desirability? oDirect vs. indirect experience (Hamilton & Thompson, 2007) oProduct trial vs. reading a product description/ad oInterruption (Goodman & Malkoc, 2012) Construal level theory (Liberman & Trope, 1998) Low/concrete level: “how-to” High/abstract level: “why” Feasibility Desirability Feasibility or Desirability? oDecision time frame: near vs. far future (Zhao et al., 2007) o1 month vs. 3 months Process Feasibility Construal level theory (Liberman & Trope, 1998) Outcome (end state) Desirability oConsumers’ process- versus outcome-focus mindset can be activated by various market condition factors. One such factor is counterfactual thinking. CFT and Feasibility and Desirability Considerations oCFT often takes the form of a conditional proposition, in which individuals identify alternative routes or processes to mutate factual events. oCFT may activate a process-focused information processing mentality and sensitize individuals to procedural information. oindividuals who engage in CFT thinking about “how” things would have turned out differently are more likely to process-focused when they are directed to mutate possible actions in the process in order to alternate outcomes (Liberman, Macrae, Sherman, & Trope, 2007; Trope, Liberman, & Wakslak, 2007). oWe expect that CFT individuals construe an activity in a manner of procedural actions. Research Hypotheses After a negative consumption episode, oH1: CFT individuals will weigh product feasibility more heavily than product desirability when making a decision in a subsequent consumption event. They will evaluate a high-feasibility product more favorably than a high-desirability product. oH2: Individuals who do not engage in CFT will weigh product feasibility and desirability equally because both feasibility and desirability considerations should be equally important when making a decision. Their preferences between a high-feasibility product and a high-desirability product should not be different. Method oStudy 1 CFT and Action Identifications oStudy 2 CFT and Feasibility (vs. Desirability) Considerations in Ad Persuasion oStudy 3 CFT and Feasibility (vs. Desirability) Considerations in Choice Preferences oReplicates the findings of study 2 using a choice task with music players and examines the underlying mechanism. Study 1 CFT and Action identifications o Purpose oTest whether CFT influences respondents’ action identifications (procedural vs. ends). oDesign oOne factor between-subjects design (CFT vs. control) oN= 56 (33 females and 23 males, aged 19-66) recruited through Mturk. oRead a job interview scenario and imagined that they missed a flight for a job interview. Study 1 CFT and Action identifications oIndependent oCFT: generate “if only” thoughts (Krishnamurthy & Sivaraman 2002) oDependent measures oBehavior identification form (BIF): a 25-item dichotomousresponse questionnaire (Vallacher & Wegner 1989) oVoting: making a ballot (how to) or influencing the election (ends)? oResults: oCFT individuals had higher preferences for the “how to” action identifications (M = .51) than the control group (M = .40, F (1, 54) = 4.85, p < .05). CFT scenario Job Interview You and a friend have to go to an important job interview in Chicago by plane today. Yesterday, your friend who is an early riser offered to pick you up at home very early this morning to go to the airport together. Since you were invited to a dinner that evening and imagined that you would be coming home a bit late that night, you considered that you could sleep an extra 15 minutes this morning if you drove yourself to the airport; you therefore declined your friend’s proposal. This morning you were so tired that you didn’t hear the alarm clock and you woke up later than expected. You quickly took a shower, brushed your teeth, got dressed, and jumped into your car to go to the airport, but you looked into the rear view mirror and noticed your neighbor had parked his car in front of your apartment and just blocked your drive way. You got out your car and spent some minutes having your neighbor remove his car. Once you got on the freeway, to your surprise, you found the traffic was slower than usual. You eventually managed to reach the airport, only to discover that your flight had just departed. Later you hear from your friend, who tells you that the interview went well, and thinks he has a good chance of being hired. You said to yourself, “what a day!” BIF (Vallacher & Wegner 1989) a. Getting organized b. Writing things down 2. Reading a. Following lines of print b. Gaining knowledge 3. Joining the Army a. Helping the Nation's defense b. Signing up 4. Washing clothes a. Removing odors from clothes b. Putting clothes into the machine 5. Picking an apple a. Getting something to eat b. Pulling an apple off a branch 1. Making a list Study 2 CFT and Feasibility (vs. Desirability) Considerations in Ad Persuasion o Purpose oInvestigate whether and how such CFT induced information processing focus influences an individual’s preference for product feasibility and desirability in an ad advertising persuasion setting. oDesign o2 (CFT: CFT vs. control) x 2 (product features: high-feasibility vs. high-desirability) between-subjects factorial design oN= 135 (undergraduate respondents in Canada) oRead a hypothetical missing flight experience episode. CFT scenario Missing Flight You bought a vacation package to Acapulco, Mexico for spring break 2009. The package includes air travel from the local city and six nights in a hotel that is close to the clubs, has a large pool, is on the beach, and includes all of your breakfasts. Your friends, who will be your roommates at the hotel, leave on the Friday before spring break, but you have a prior commitment and have to leave on Saturday. You are really looking forward to getting away from the cold. On Saturday morning, you board the plane from your hometown to Chicago. You have to transfer to a different plane in Chicago. When you get to Chicago, you quickly check the screen inside the terminal and see that your flight is leaving from gate B1. When you get to B1, you find there are no people waiting in the gate area. You go to an airline agent behind the counter and ask when the flight to Acapulco, Mexico leaves. She checks her screen and says, “I’m sorry, you have come to the wrong gate. The correct departure gate is H64, which is in another terminal.” You can not believe it and double check the screen. The airline agent is right and you have misread the screen earlier. CFT scenario Missing Flight Your flight will departure in 35 minutes. It will take about 15 minutes to ride the connection train to get to gate H64. The airline agent informs you that she can call an express cart to transport you to gate H64 in 10 minutes and charge $25 for the service. You feel you have plenty of time and decide to take the train to gate H64. So, you follow the signs and take a walk to the train station. It takes you five minutes. You barely miss a leaving train when you get to the station and have to wait a couple of more minutes for the next train. Eventually, you board the train and sit down. Five minute later and after a couple of stops, you suddenly realize you are going in the wrong direction. You quickly get off the train at the next stop, wait a couple of more minutes at the station, and board the right train. About 15 minute later, the train stops at your terminal. You jump off the train and run toward to gate H64. When you get to gate H64, you find there is no one in the gate area, except an airline agent. When you approach her and tell her that you are here for the flight to Acapulco, she says, “I’m sorry, we have just finished boarding that flight. The airplane has pulled away from the terminal. You’ll have to go to the customer service desk around the corner. They will reschedule you for the next available flight.” You go to the customer service desk and only to find out that the next available flight will be in tomorrow Sunday afternoon.” You find yourself a seat, sit down, and say to yourself, “what a waste of time! I waste two days of my break!” Study 2 CFT and Feasibility (vs. Desirability) Considerations in Ad Persuasion oIndependent oCFT: generate “if only” thoughts (Krishnamurthy & Sivaraman 2002) oDependent measures oAd evaluations ( = .93), product evaluations ( = .91), purchase intentions ( = .86) oAd focus: product feasibility and desirability oResults: oManipulation check: The high-feasibility product (M = 5.23) was rated higher than the high-desirability product (M = 4.53, F (1, 133) = 4.58, p < .05) on product feasibility whereas the high-desirability product was rated higher than the high-feasibility product (p < .05) on product desirability. Study 2 Results 7 High Feasibility Low Desirability Ad Attitude 6 High Desirability Low Feasibility 5 4 Purchase Intention 7 High Feasibility Low Desirability 6 High Desirability Low Feasibility 5 4 3 3 2 CFT Control Counterfactual Thinking 2 CFT Control Counterfactual Thinking Study 3 CFT and Feasibility (vs. Desirability) Considerations in Choice Preferences oPurpose oReplicates the findings of study 2 using a choice task with music players and examines the underlying mechanism. oDesign o2 (CFT: CFT vs. control) x 2 (choice features: high-feasibility vs. high-desirability) between-subjects factorial design oN= 171 (undergraduate respondents in a Midwestern State) oRead a hypothetical digital camera consumption scenario. oLooked for a MP3 player with a voice recorder in order to complete a course project. Study 3 CFT and Feasibility (vs. Desirability) Considerations in Choice Preferences oIndependent oCFT: generate “if only” thoughts (Krishnamurthy & Sivaraman 2002) oDependent measures oProduct evaluations ( = .92), purchase intentions ( = .94) oMediator oImportance of product features (easiness to use and simplicity to operate) CFT scenario Broken Camera Imagine that it is the beginning of the summer. You are about to go on a vacation with your best friends, which you’ve been looking forward to for a long time. You want to capture all the great moments and scenery when you are on vacation, so you bring your brand new digital camera. You just bought the camera a couple of weeks ago and invested a good deal of time, money, and effort on buying the camera. It is your favorite model and you love it very dearly. Now, you are with your friends at your dream vacation place in southern Florida. It is a gorgeous day though the temperature is high. You and your friends arrive at a beautiful beach. You leave your brand new camera on the sand beside your backpack and jump into the water. After playing a while in the water, you want to take some pictures to capture the fun moments. You go back to the beach, pick up your camera and try to turn on the camera. It does not work. You try several other things, nothing works. You get your friends to help, but no one can figure out the problem. You are upset and feel very frustrated and eventually, you give up on the camera. That day, you keep wondering: “what happens to my new camera?” CFT scenario Broken Camera After getting home, you call the 1-800 service number that came with your camera. You talk to the representative on the phone. After some checking, the representative says that you should bring the camera to the service facility. You drop it off at the service facility. Two days later, you get a call from the service center. It turns out that the camera battery was overheated and burned due to high heat. The camera was severely damaged. The repair charge will be costly without the manufacturer warranty. You realize that this warranty does not cover circumstances beyond the manufacturer’s control, nor problems caused by failure to follow the care and operating instructions listed in the manual. You go back home and read the user’s manual. You find the user’s manual indeed warns users the particular conditions (including beach) under which to operate the camera. It calls for user’s care and lists a couple of precautious measures for preventing potential damages to the camera and especially to the particular battery in the camera. You say to yourself, “what an unfortunate experience!” High-feasibility High-desirability “First, this player has a good overall rating (3.5 out of 5 stars). Secondly, this model gives you an average sound recording quality with one fixed recording quality setting at a WMA-formatted 56Kbps. The average recording quality probably will not impress your professor and also may make it harder for you to transcribe the voice recordings. Thirdly, it has a 2GB integrated flash memory, with which you can record up to 7 hours interview. “First, this player has an excellent overall rating (4.5 out of 5 stars). Secondly, this model gives you a super sound recording quality with an adjustable recording quality setting that tops out at a WMAformatted 128Kbps. The super recording quality may impress your professor and also makes it easier for you to transcribe the voice recordings. Thirdly, it has a 4GB integrated flash memory, with which you can record up to 10 hours interview. However, this player is easy and straight forward to use. It does not require the user to manually set the recording modes or recording quality settings. In addition, it has a build-in microphone for recording, which does not need any extra time to install the driver software or to connect and set up a microphone. It is ready for voice recording at any time.” However, this player requires the user to manually set the recording modes and recording quality settings every time before starting voice recording. In addition, it requires a plug-in microphone for recording, which takes approximately 15 minutes to download and install the driver software, to connect and set up the microphone.” The CNET editor summarizes the bottom line as: “Some limitations on creating high quality of voice recordings and smaller memory size, but quick to set up and easy to operate.” The CNET editor summarizes the bottom line as: “Creation of excellent quality of voice recordings and larger memory size, but time consuming to set up and tedious to operate.” Study 3 Results 6 High Feasibility Low Desirability 5 High Desirability Low Feasibility 4 Purchase Intention Product Attitude 6 High Feasibility Low Desirability 5 High Desirability Low Feasibility 4 3 3 2 2 CFT Control Counterfactual Thinking CFT Control Counterfactual Thinking Mediation Effect (Zhao et al., 2010) a=.91** Importance of Product Feasibility a x b = .74, 95% C.I. = .29 to 1.25 b=.81** Product Evaluations CFT x Product Attributes c=.80* Conclusions oAmong the few studies that strike a relationship between CFT and information processing. oAdvances our understanding of how reflecting a past consumption episode could influence individuals’ considerations in product choice preferences. o Demonstrates that CFT induced by a prior consumption episode could influence individuals’ subsequent information processing and choice preferences. o CFT individuals evaluate high-feasibility products more favorably than high-desirability products. oProvides additional evidence to the CFT literature in regard to the content-neutral pathway (Epstude & Roese, 2008). o Another content-neutral effect: construal level Makes a contribution to construal level theory by demonstrating the effect of CFT on construal level. o o Psychological distance: temporal distance, spatial distance, social distance and hypotheticality Counterfactual Thinking and Consumer Health Choice Preferences and Behaviors KAI-YU WANG, BROCK UNIVERSITY, CANADA MELISSA BUBLITZ, UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN -OSHKOSH, USA GUANGZHI ZHAO, LOYOLA UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND, USA Introduction oObesity is a serious and costly disease throughout the world, particularly in North America. oOver 1/4 of Canadian adults and 1/3 of American adults are obese (Ogden, Carroll, Kit, and Flegal, 2012; PHAC and CIHI 2011). oThe costs of obesity, including medical care and loss of worker productivity, are substantial (America: $270 billion; Canada: $30 billion) and rising (Society of Actuaries 2011). oHealth problems such as diabetes and heart disease oOther adverse effects: self-esteem and depression Research Objectives oHealth halo effects (i.e., cognitive biases) oIndividuals’ judgments in terms of healthy eating and living habits are not always correct. oWhen asked to think about alternatives, they are more likely to correct health halo effects (Chandon & Wansink, 2007). oWe propose that CFT, reflecting upon past events and generating possible alternatives, influences the effectiveness of health communications and individuals’ health decisions. oProvide recommendations for designing effective health messages for social marketing strategies. Research Hypotheses oH1: When respondents engage in CFT, they evaluate high feasibility-low desirability choices more favorably and are more likely to adopt the advertised choice than high desirability-low feasibility choices after experiencing a diet plan failure. The reverse effects are observed for respondents who do not engage in CFT. Literature Review oGoal pursuit (Gollwitzer et al., 1990) oDeliberative mindset: weigh the pros and cons of potential goals. oImplemental mindset: engage individuals to think about when, where and how to implement a chosen goal. oImplementation intentions can olead to immediate action initiation (Brandstatter, Lengfelder, and Gollwitzer 2001). ohelp individuals’ to meet their health goals (Adriaanse, Gollwitzer, De Ridder, Wit, and Kroese 2011). oIf CFT can activate a process-focused (i.e., “how to”) cognition orientation as proposed, CFT should induce an implemental mindset and a high feasibility-low desirability choice will further facilitate their action initiation. Research Hypotheses oH2: Respondents who engage in CFT and make a high feasibility-low desirability choice produce greater behavioral outcomes than those who make a low feasibility-high desirability choice and than those who do not engage in CFT, regardless of their choice. Research Framework Feasibility (vs. desirability) Ad Current Dieters Role of Self Monitoring (Burke et al., 2011; Kong et al., 2012) Tracking Behavior Health Behavior/ Outcome Study 1 CFT and Feasibility (vs. Desirability) Considerations in Ad Persuasion and Behavior Outcomes o Purpose oInvestigate whether and how such CFT induced information processing focus influences an individual’s preference for health service feasibility and desirability in an ad advertising persuasion setting and its behavior outcome. oDesign o2 (CFT: CFT vs. control) x 2 (product features: high-feasibility vs. high-desirability) between-subjects factorial design oN= 120 (undergraduate respondents in Canada) oRead a hypothetical new year’s resoultion episode. CFT scenario New Year’s Resolution Imagine that at the start of this year (January 1, 2013) you made a New Year’s Resolution to make more healthy choices and eat reasonable sized portions with the goal of losing weight and feeling better. Essentially you decided you would go on a diet! For most of January things were going great. It was beginning to pay off; you had lost several pounds and were feeling great. However, on February 3rd you went to a big Super Bowl party. It had been a while since you indulged in your favorite snack foods and you hadn’t had pizza or chicken wings since starting your diet. Your favorite pizza is served; everyone is having a great time. When you try to pass on a second piece of pizza your friend says “you have been so good, you deserve to enjoy yourself once and a while, you can always go back on your diet tomorrow” so you eat more than you had planned on. When the team you are rooting for scores you get excited and want to celebrate, you end up drinking more you had budgeted for the night even though low calorie sodas and water were also available. Since that time you have had trouble getting your diet back on track. You have gained back the weight you lost in January and just can’t seem to find the motivation to stay on your diet. Phase I: CFT and Feasibility (vs. Desirability) Considerations in Ad Persuasion oIndependent oCFT: generate “if only” thoughts (Krishnamurthy & Sivaraman 2002) oDependent measures oAd evaluations, web service evaluations oMediator oImportance of service features (easiness to use and simplicity to operate) oControl oWeight control service experience and importance, height and weight Phase II: CFT and Feasibility (vs. Desirability) Considerations in Behavior Outcomes oAfter using participants to use the service for two weeks,… oDependent measures oWeb service use evaluations, general and feature use frequency, food intake tracking frequency, self-monitoring oBehavior outcome measures oReports of progress, nutrition, fitness Expected Results Feasibility Ad Tracking Frequency Desirability Ad Feasibility Ad Desirability Ad CFT No CFT Dieters No CFT CFT Non-Dieters Thank you! QUESTIONS AND COMMENTS?