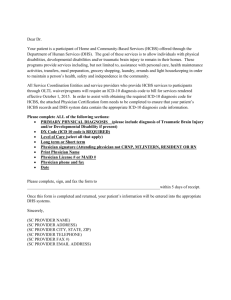

ME HCBS for Adults w/Other Related Conditions (0995.R00.00)

advertisement