Implications of Rationality Asymmetries for Food Choice and Food

advertisement

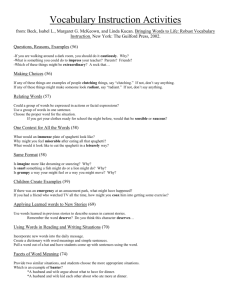

Food Marketers and Consumers: Implications of Rationality Asymmetries for Food Choice and Health David R. Just Charles H. Dyson School of Applied Economics and Management Cornell University Food Choice and the Rational Man ► Food policy is often designed based on the idea that individuals use information efficiently The consumer will use available information Can weigh the various consequences of their actions Gives appropriate weight to vague or narrow information ► Individuals make more than 300 food related decision each day Paying close attention to each would be a waste of time We naturally fall back on heuristics, habits and rules of thumb The Implications of Heuristic Choice ► Heuristics are at best approximations They are subject to serious error under the wrong conditions E.g., clean plate rule can be reasonable under some circumstances and not in others May represent misperceptions ► The implication The consumer makes systematic errors The consumer could be better off ►Cognitive costs are prohibitive Implications of Heuristics ► Policymakers can make people better off Save people from themselves (?) ► We need to be careful to separate our preferences from theirs ► Could provide a justification for policymakers to impose their preferences People may resist changes that make them better off ► My ► Widens perceptions are still my perceptions the set of policy tools Before: price, information, content regulation Now: Regulating decision context Some General Principles ► Subtle ► factors can influence choice Suggestive names, lighting, shapes, colors, image, etc. Marketers have used this to advantage In food decisions, much of the problem stems from not being able to monitor consumption Monitoring consumption requires cognitive resources Factors that make this task more difficult tend to increase consumption Individuals distort perceived consumption proportional to serving size Containers or packaging can make monitoring easier ► We are different people when we are distracted An Extended Example: Portion Sizes and Purchasing ►A lot has been said about mega-sized portions Super-size me phenomenon Long literature documenting the increase in portion sizes since the 70s Not just in restaurants, but also in home recipes ► What is a normal portion size anyway Soda can – 12 oz Starbucks – “Tall” 12 oz (no normative size) McDonald’s soda – “child” 12 oz (medium is 21 oz) McDonald’s coffee – “small” 12 oz (medium is 16 oz) Normative Portion Sizes ► Food marketers put a lot of effort into these normative size names ►E.g., Wendy’s offers a Single burger, Double, Triple, a Jr. and a Double Jr. Deluxe (!) ► Why do food retailers use such normative language? ► Two possible motivations ►Informational ►Framing Standard Models of Portion Size ► Economists propose that different sizes are used to price discriminate Some value higher quantity, others don’t Larger quantities are offered at a volume discount Those who value more benefit from discount Those who don’t benefit (weakly) from smaller quantity being offered Profits increase ► Quantity determines utility Quantity ► Fast Food and Cafeterias Sizes are usually on display Sizes are often posted next to the normative names ► What extra information could the labels provide? Information about what others are doing? Information about what they want you to buy? Framing Effects ► How we phrase the question affects the answer (Tversky and Kahneman) ►Imagine that the U.S. is preparing for the outbreak of an unusual Asian disease, whish is expected to kill 600 people. Two alternative programs to combat the disease have been proposed. Assume that the exact scientific estimate of the consequences of the program are as follows: ►If Program A is adopted, 200 people will be saved (72%) ►If Program B is adopted, there is a 1/3 probability that 600 people will be saved and another 2/3 probability that no people will be saved (28%) ►If Program C is adopted, 400 people will die (22%) ►If Program D is adopted, there is a 1/3 probability that nobody will die and 2/3 probability that 600 people will die (78%) Framing Effects ► People measure utility against reference points Lower marginal utility for gains than for losses Ratio about ½ ► Benartzi and Thaler find evidence in stock prices ► Tversky and Kahneman suggest that framing impacts are prevalent in consumption decisions. ► Normative size names could establish a reference point Regular is the status quo Upgrades above not as valuable as downgrades below A Model of Framing Sizes ► Suppose individuals solve max U x | xC ► Subject ► Where to p x x y X is a vector of quantities purchased C is the set of available quantity choices (including origin) p (x) is price (possibly nonlinear) θ is a vector of quantities given the normative label A Model of Framing Cont. ► Loss aversion implies if xi 0 Ui x | 0 1 2 1 2 U x x | U x x | if i xi i if xi 0 Ui x | 0 if i j U x ji x | 0 i i Implications of Framing ► Claim 1: Let x be any positive consumption quantity available for consumption good i and suppose that the individual displays loss averse preferences. Increasing the reference point must decrease the willingness to pay for x. Implications of Framing ► Claim 2: Let x x be any two consumption quantities for a consumption good i and suppose that the individual displays loss averse preferences. If i x, x , then increasing θi will increase the willingness to pay for x relative to x . Implications of Framing ► Claim 3: Let x x be the only two positive consumption quantities available for consumption good i and suppose that the individual displays loss averse preferences. Changing the reference point from i x to i x may decrease the probability of purchasing either xi x or xi x . Framing ► Three hypotheses Increase norm – ambiguous change in probability of purchase (unless only other choice is 0, then decreases) Increase norm – increase the WTP to upgrade Increase norm – decrease WTP for all sizes of goods ► Implication for managers Decrease normative sizes. Our Experiment ► Subjects were recruited for a lunch experiment Cornell Students Conducted at one of the campus dining facilities ► Paid $15, they purchase lunch and keep the change ► Items include spaghetti in meat sauce, salad, pudding, rolls, soda and water. Our Experiment ► Two different sizes were offered (one twice as large as the other) for Pudding Spaghetti Salad ► Sometimes the sizes were labeled “Half” and “Regular” ► Sometime they were labeled “Regular” and “Double” Part I: An Auction ► 45 Participants (20 Regular/Double, 25 Half/Regular) ► All viewed the items before bidding ► We ran a special nth price auction for each multiple sized item Asked for their maximum willingness to pay for the smaller Asked their maximum additional willingness to pay for the larger ► 15th highest bid determines sale price of the larger ► 3rd lowest bid determines the smaller Demographic Information Variable Gender (1 = Female) Height (inches) Weight (pounds) Age HALF 0.53 (0.51) DOUBLE 0.42 (0.51) Z-Stat 0.641 (0.52) 67.9 (4.3) 145 (26) 19.3 (1.2) 67.9 (5.1) 147 (25) 19.7 (2.2) 0.175 (0.86) -0.095 (0.92) -0.033 (0.97) Average Bids by Treatment Variable Small Spaghetti*** Large Spaghetti*** Small Salad** Large Salad** Small Pudding** Large Pudding*** d Spaghetti** d Salad** d Pudding*** HALF Mean N = 25 $1.07 (1.06) $1.67 (1.60) $0.71 (0.98) $1.08 (1.33) $0.44 (0.40) $0.62 (0.63) $0.63 (0.68) $0.37 (0.51) $0.18 (0.31) DOUBLE Mean N = 20 $2.18 (1.02) $3.50 (1.82) $1.18 (0.78) $1.71 (1.06) $0.89 (0.71) $1.53 (1.02) $1.31 (1.25) $0.58 (0.35) $0.64 (0.53) Z-Stat (P-Value) -3.400 (0.00) -3.378 (0.00) -2.428 (0.02) -2.199 (0.03) -2.288 (0.02) -3.087 (0.00) -2.539 (0.01) -2.167 (0.03) -3.406 (0.00) Average Treatment Effects (Controlling for Demographics) Variable Small Spaghetti Large Spaghetti Small Salad Large Salad Small Pudding Large Pudding d Spaghetti d Salad d Pudding Model 1 $1.13*** (0.33) $1.82*** (0.55) $0.39 (0.31) $0.38 (0.42) $0.43** (0.18) $0.84*** (0.28) $0.68** (0.32) $0.05 (0.16) $0.41*** (0.15) Model 2 $1.11*** (0.36) $1.86*** (0.62) $0.29 (0.37) $0.21 (0.48) $0.36* (0.20) $0.76*** (0.29) $0.75** (0.35) $0.01 (0.17) $0.40** (0.16) Change in WTP for Larger Size CDF of Bids 0 1 Cumulative Probability 1 .05 0 5 Bid for Small Spaghetti CDF of Bids 0 1 Cumulative Probability 1 .05 0 8 Bid for Large Spaghetti CDF of Bids 0 1 Cumulative Probability 1 .1 0 6 Bid for Spaghetti Upgrade Interpretation ► There are substantial incentives to name the sizes correctly Total bids increased from $3.37 to $6.97 (P = 0.00) ► The effect was much stronger for the hedonic item Salad increased in price by 66% and 60% respectively Pudding increased by 102% and 147% respectively Spaghetti increased by 105% and 108% respectively ► Note on size of bidding pool Interpretation ► All bids increase with smaller normative size This is not consistent with LA ► Bids for larger sizes are bigger for regular to double than for half to regular This is also inconsistent with LA ► Hunger attenuates significance (somewhat) Visceral effects (Loewenstein)? Part II: Cafeteria Purchasing ► 134 participants ► Same foods and conditions ► Participated for 2 weeks First week only the regular Second week only the half or the double ► Some weeks participants participated only in some Allows us to check for order effects (none detected) Cafeteria Prices Small Spaghetti ► Large Spaghetti ► Small Salad ► Large Salad ► Small Pudding ► Large Pudding ► $2.50 $3.50 $1.50 $2.00 $1.50 $2.00 ► ► ► ► Roll $0.50 Pepsi $1.00 Ginger Ale $1.00 Water $1.00 Consumption Behavior Variable HALF Spaghetti Waste*** Salad Waste** Pudding Waste Total Calories Consumed*** Proportion Purchasing Spaghetti*** Salad Pudding Rolls Soda Water 2 (27) 7 (19) 22 (71) 463 (231) DOUBLE Z-Stat (P-Value) 20 (53) 3 (17) 11 (52) 325 (235) 5.348 (0.00) 2.435 (0.01) 1.346 (0.18) 2.854 (0.00) Large Only Spaghetti Waste*** Salad Waste** Pudding Waste** Total Calories Consumed*** Proportion Purchasing Spaghetti** Salad Pudding Rolls*** Soda Water 0.705 (0.459) 0.302 (0.463) 0.312 (0.466) 0.434 (0.500) 0.169 (0.377) 0.113 (0.320) 0.573 (0.497) 0.566 (0.499) 0.417 (0.496) 0.447 (0.501) 0.563 (0.499) 0.658 (0.478) Small Only 7 (27) 18 (42) 1 (13) 3 (10) 6 (25) 14 (41) 231 (139) 305 (146) 4.259 (0.00) -1.420 (0.16) 0.879 (0.380) 0.093 (0.93) -0.403 (0.69) -1.267 (0.21) 0.413 (0.495) 0.375 (0.487) 0.163 (0.371) 0.469 (0.502) 0.354 (0.481) 0.500 (0.503) -2.519 (0.01) -0.542 (0.588) -0.961 (0.34) -2.999 (0.00) -1.580 (0.11) -1.028 (0.30) 0.632 (0.487) 0.421 (0.498) 0.228 (0.423) 0.697 (0.462) 0.474 (0.503) 0.579 (0.497) -3.03 (0.00) -2.265 (0.02) -1.986 (0.05) -2.65 (0.01) Controlling for Demographics Variable Spaghetti Waste Salad Waste Pudding Waste Total Calories Consumed Spaghetti Waste Salad Waste Pudding Waste Total Calories Consumed Model 2 Model 1 Large Only -82*** (20) -86*** (18) -7** (3) -5 (3) -3 (14) -18 (12) -83 (53) -102** (46) Small Only 12* (7) 13** (6) 1 (3) 1 (2) 10 (8) 8 (7) 58** (28) 76*** (25) Change in Average Calories Percent Purchasing Interpreting ► People regular consume more calories when we call it a 32% or 36% depending on size ► Probability of purchase goes both ways (only significant up when regular) Seems to depend on type of dish LA says decreases ► People use size names to determine how much to leave! Implications ► Willingness to pay responds to normative language Significant increases in WTP by lowering norm (like a social norm) Upgrades more valuable above the norm (violates LA, also inconsistent with social norms) “Regular” increases purchase only for some foods (like loss aversion) ► Do we need another model? Maybe the label is informative Labels as Information ► Individuals respond poorly to visual cues Can’t estimate size well (tall vs. short) Respond to plate and utensil size We eat with our eyes (soup bowls) ► What if people use names as a crutch I know about how much I am willing to pay for a “regular” – but adjust for perceived size Double that for a double (with some adjustment downward) Halve it for a half (with some adjustment upward) ► Might explain the plate waste Implications for Retailers ► Higher WTP for larger names may encourage larger and larger portions Credibility issues may lead to a treadmill ► Responds like an anomaly Exacerbated by stress, hunger, distractions Thus, normative sizes more effective in fast food or convenience food What about more hedonic food? Factors Affecting Food Choice ► Cognitive Experiential Self Theory (Epstein, 1993) Two systems used to evaluate every stimulus Experiential system makes snap judgments based on affect Cognitive process makes deliberative evaluations based on rational thinking Processing resources (time, stress, distractions) determines which rules ► ► ► When resources are few, convenience, affect, and salience dominate When resources are many, prices and health information Hedonic vs. utilitarian foods “wants” vs. “shoulds” More willing to acquire a should than give up a want Significant reactance Consumption and Control Preferences Wealth Cognitive (Low Impact) Consumption Decision Affective (High Impact) Price Price of Substitutes and Complements Attributes (calories, nutrients) Health Information Effort Salience Structure Size of portions Hedonic (Salt, Fat, Sugar) Atmosphere Effort/Availability Distractions Size of portion Shape of containers Primitive Manufacturer Control Individual Control Visceral Factors (hunger) Mental food accounts Commitment Socialization Habit The Role of Marketing ► ► ► Individuals control some of the important factors Food manufacturers, retailers and marketers control the majority of factors Hence, consumption decisions (food and amount) are the result of a game between manufacturers and consumers Consumers are not entirely aware of their behavior Marketers are! ►Or ► maybe just behave ‘as if’ This is a mechanism design problem Could result in a loss of wellbeing due to incomplete or asymmetric information Does asymmetric rationality work the same way? The Consumer ► The consumer problem can be represented as max U uc q 1 ua q | s ps qQs , sS ► Where ϕ is the level of cognitive resources determined exogenously At least the individual isn’t aware of how their actions affect it variable s is an external cue that influences choice, like portion size ► The variable q is the choice variable (e.g., quantity) that influences utility (taste and health) ► The Food Manufacturers/Retailers ► Food sellers wish to maximize profits To do this they choose the available cues (S ), prices and the available choices (QS ) Of course sellers may respond to heuristics also ►I assume that over time they happen upon the profit maximizing choice sets They behave as if they know the consumer’s active preferences A Model of Food Transactions ► The producer solves max ps k (q, s ) c q, s S ,Qs , ps subject to max U uc q 1 ua q | s ps qQs , sS ► Here k is the unit for which the individual is charged Package size, or quantity consumed, etc. Asymmetry of Rationality ► The seller knows she will receive ps * k (q*, s*) c q*, s * ► The consumer behaves as if there is probability ϕ of receiving uc q * ps * and probability (1- ϕ) of receiving ua q*| s * ps * ► In actuality the consumer always receives uc q * ps * The Impacts of Heuristics ► Let q (Qs , S , ps ) arg max uc q ps qQs , sS Heuristics are non-trivial if q (Qs , S , ps ) q *(Qs , S , ps ) ► The most important points: Consumers are not the only ones who respond to policies Consumers do not always respond as expected Is it Always Better to be Rational? • The impact on overall welfare also depends on how the heuristic preferences impact profit. • Suppose for instance that individuals are charged for q, costs are monotonic in q and that s is costless (~ denotes fully rational eq) • There are 4 potential cases comparing to fully rational equilibrium • Depends on the relationship of uc ? U * U * uc ? c * c An Example: Portion Size ► As a simple example, suppose we consider the portion size problem max p c s s, p ► Subject to uc min q* s, p , s 1 ua min q* s, p , s | s p U An Example: Portion Size ► Increasing ds 0 d iff distractions increase portion size, uc ' s ua s | s ua s | s q s ► If marginal affective utility is larger than cognitive utility Affective here refers to the deviation from ex post wellbeing Sin and Virtue ► This leads us to define two different types of foods Virtuous Sinful uc ' s ua s | s ua s | s q s (marginal affective utility lower) uc ' s ua s | s ua s | s q s (marginal affective utility higher) ► Consumers over consume sinful foods and under consume virtuous foods Sin and Virtue ► Result 1: As cognitive resources decrease, portion sizes will increase more for more sinful foods and could decrease for virtuous foods We should see some separation ► Result 2: As cognitive resources decrease, uniformly more sinful foods will be marketed Hard to market health as convenience food If marketing sinful foods, you want to encourage distraction Sin and Virtue ►I will present some graphical examples using sinful foods Many things flip when we examine virtuous foods I will comment on how this changes things without showing the graphs ► Graphs assume linear costs, and a strong version of sinful Cognitive arg max is lower, and maximum is lower Much more richness if this is not the case, but the simple model demonstrates how unintended consequences can happen 100 90 Money Metric Utility 80 70 60 50 Affective 40 Perceived Utility Cognitive 30 20 10 0 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 Portion Size 100 90 80 70 Profit 60 50 Profit 40 Cognitive Affective 30 20 10 0 0 2 4 6 8 10 Portion Size 12 14 16 18 20 Taxing Size ► The constraint now becomes uc min q* s, p , s 1 ua min q* s, p , s | s p ts U ► In equilibrium, ► Producers 𝑑𝑠 𝑑𝑡 = 1 𝑆𝑂𝐶 <0 lose out on profit Loss must be greater than ts ► Consumers welfare will improve if sinful, and Δ𝑢𝑐 > Δ𝑝 + 𝑡𝑠 100 90 Money Metric Utility 80 70 60 50 Affective 40 Perceived Utility Cognitive 30 20 10 0 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 Portion Size 100 90 80 70 Profit 60 50 Profit 40 With Tax 30 20 10 0 0 2 4 6 8 10 Portion Size 12 14 16 18 20 Welfare: Taxing Large Portions ► Producers will always perceive a loss of Profit ► Consumers will too if any surplus shared This will be unpopular with all involved in the transaction ► May or may not increase consumer welfare Depends on how sinful the food is Reactance can also either increase or decrease welfare ► Incentive to reduce cognitive resources persists If they can influence this at some cost, the equilibrium will be lead closer to the non-regulation Welfare: Subsidizing Large Virtuous Portions ► Profits to the firm increase ► Consumers may also if surplus is shared Thus this may be a very popular program with all involved in the transaction ► Will always increase consumer welfare ► Incentive to increase cognitive resources persists ► Food may go to waste if subsidy exceeds decline in perceived utility Regulating Context ► Suppose context instead we considered regulating Naming of portion size? Requiring an important cognitive cue ► Suppose we could shift the perceived utility closer to the cognitive utility Could try to increase cognitive resources (distractions) Could try to alter affective utility function (names, atmospheric cues) 100 90 Money Metric Utility 80 70 60 50 Affective 40 Perceived Utility Cognitive 30 20 10 0 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 Portion Size 100 90 80 70 Profit 60 50 Profit 40 Cognitive Affective 30 20 10 0 0 2 4 6 8 10 Portion Size 12 14 16 18 20 Welfare: Regulating Context Cues ► By increasing cognitive resources Profits decrease Consumers may still perceive they are better off if surplus is shared ►More likely the larger the shift in perception ► Consumer will be better off if small change ► If instead, shifting the affective curve Profits may increase This may be more politically feasible Regulating Context for Virtuous Foods ► Increasing cognitive resources and/or reshaping the affective curve will Increase profits Increased consumer perceived welfare if surplus is shared Thus this would be popular with actors ► Consumer will be better off Conclusion ► Ignoring away behavioral economics won’t make it go Even very traditional policies may interact with behavioral cues ► Could make policies ineffective or even self defeating ► Regulators may be able to use behavioral cues to create much more promising policy options Policies that potentially improve profits and welfare Such creative solutions have proven to be very effective in some contexts Could also allow win/win solutions Need to know what we cannot observe