Chapter 2- History of School Finance

advertisement

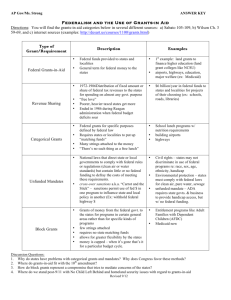

Chapter 2 History of School Finance Our founding fathers profoundly believed that their new democracy’s health depended on its people’s virtues as right, honorable, ethical individuals as well as knowledgeable citizens. Founding Fathers Believed Public Education Essential Rousseau noted in 1758 that “public education…is one of the fundamental rules of popular or legitimate government”. Jean Jacques Rousseau, A Discourse of Political Economy, 1758, translation and introduction by G.D.H. Cole in The Social Contract and Discourses, London: J.M. Dent & Sons, 1973), p. 149. An educated general populace required for its democratic republic’s survival The first American school finance laws date back to the Massachusetts Act of 1642, which required parents and masters to attend to the educational duties of the colony’s sons and servants. “The General Court (the colonial legislature) empowered ‘certain chosen men’ of each town to ascertain, from time to time, if the parents and masters were attending to their educational duties; if the children were being trained in learning and labor and other employments…profitable to the Commonwealth .” Early U.S. Value in Education “The child is to be educated, not to advance his personal interest, but because the state will suffer if he is not educated.” “Profitable to the state” “Profitable” meant that sons and male servants learned to read and understand religious principles while they received training in “learning and labor”. Women stayed home and learned household tasks and embroidery– an obvious Title IX violation today. “Ye Olde Deluder Satan” Laws Within five years of the first school finance law, however, it failed; The law presumed that those who could read & understand the Bible couldn’t be tempted to follow Satan’s wiles. Different Sized Settlements Had Varying Requirements for Providing Public Schooling • For 50 or more households - Appoint a reading and writing teacher Pay what deemed appropriate • For settlements of 100 or more households – Community taxed property owners to provide a grammar school Towns not meeting this educational requirement faced a financial penalty. Who Paid for Schools? • Founding fathers believed that the wealthy should pay for education’s public and religious functions. • Local government taxed property because people in those days considered land to be a valid measure of wealth. The Law of 1647 Represented a Distinct Step Forward • Not only did the law order towns to establish a school system – elementary for all towns & children, and secondary for youths in the larger towns – but • For the first time among English-speaking people, there was an assertion of the right of the State to require communities to establish and maintain schools. Failure to do so resulted in penalty. The Laws of 1642 & 1647 Represent the foundations upon which our American state public-school systems have been built. They also established the State’s right to tax for the provision of education. Massachusetts’ Precedent Establishing property taxes as the basis for funding public schools quickly caught on in other New England colonies. It remains a tradition to this day. Compromise to Appease State’s Rights Advocates & Federalists Since the first 10 Amendments do not mention “education”, it became a state function. Who is Responsible for Public Schools? • This compromise, however, has farreaching legal and financial effects today. • State’s rights continues to be a discomforting national issue with keen influence on educational policy and practices. Taxing Property Evolved Somewhat Differently in Various Regions The middle and southern colonies, for example, subsidized very basic public schools (small facilities, limited curriculum, few students attending) Mostly churches & parents financed further education. Education = Prosperity States must invest as heavily in education as their capacity allows if they want future economic prosperity for all its citizens. Regional Evolution of Schools & School Financing 1. Good school conditions 2. Mixed conditions 3. Pauper & parochial schools 4. “No action” group Schools’ Evolution Differed in Various Geographic Regions • New England became the first English-speaking area that required children learn how to read • Although religious in inspiration and scope (students would be able to interpret the Bible for themselves and save their immortal souls), knowing how to read and comprehend also allowed individuals to think for themselves and act without offense or injury to others Good School Conditions • Citizens generally valued education and saw its value for the “entire”* populace • Provided public financial support to educate large number of students * White Male • Maine • Vermont • New Hampshire • Massachusetts • Connecticut • New York • Ohio Mixed Conditions Schools People held conflicting ideas about what education should be and what it should provide for children. Showed wide variance in their willingness to fund local schools and in resulting education quality. • Indiana • Illinois Pauper & Parochial School • Believed that high-quality schooling was for the elite • Privileged sent their children to churchsponsored (parochial) schools • Community leaders believed that the poor (paupers) deserved a minimal level of education • Pennsylvania • New Jersey • Delaware • Maryland • Virginia • Georgia • South Carolina • Louisiana “No Action” Group Philosophically, these colonists believed that “government” should play little role in citizens’ or community affairs. Individuals held responsibility for their own actions and well-being, including providing for their children’s education. • These regions took little or no actions establishing public education in their early statehood. • Rhode Island, Kentucky, Tennessee, North Carolina, Mississippi, and Alabama. Not All States Fit These Categories • A number of states reflect an amalgam of people and ideas, not fitting one distinct pattern. The BEST Schooling Model • The Good School Conditions model offered its eligible children the best learning opportunities. Federal History of School Funding • Even though the Constitution made education a state responsibility, the federal government did not abandon involvement with public schools or leave their financing solely to the states • On the contrary, the federal government heavily promoted and financed education from before the Constitution was ratified Federal Financial Involvement in Education In 1778 Congress eagerly sought ways to generate revenue for the new country and to pay its war debts. One method involved selling claim to western territories. Ordinance of 1785 New Congressional townships in the western territories should be six miles square (or thirty-six square miles) The six miles square would be surveyed and divided into thirty-six lots, each of one square mile Towns could set aside the proceeds from lot number 16 to finance their public schools Early School Financing Northwest Ordinance of 1787: Authorized land grants to establish education Magnificent rhetoric but little guidance about how to carry it out Ordinance of 1787: Conveyed approximately five million acres to land speculators The Ordinance Included: “Religion, morality, and knowledge being necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind, schools and the means of education shall be forever encouraged.” New States Required to Provide Education The Northwest Ordinance also established the requisite conditions for territories to become states and included a provision that each state have an education provision within its basic laws. Clarifying the “Sixteenth Section’s” Township Intent • Required monies • Federal & state from this section’s sales be spent for public schools • Started with Ohio roles clarified 4th “Wave” of Federal Policy • States would receive “a 5%” portion of the sale of public lands & states agreed that federal lands within states would be exempt from state taxes • These revenues added to monies available to establish public schools Andrew Jackson’s Presidency • There was a move to decentralize the federal government • In 1836, the Surplus Revenue Deposit Act gave $28 million of federal funds to the states • Much of this windfall was spent for public schools Another Major Federal Financing of U.S. Education • In 1802, Congress enacted legislation establishing • • • • the U.S. Military Academy In 1845, established the Naval Academy In 1876, founded the Coast Guard Academy In 1936, founded The Merchant Marine Academy In 1954, started the U. S. Air Force Academy 1862, Congress Established the Morrill Act Authorized the states to use public land grants to establish and maintain agricultural and mechanical colleges Assured the country’s economic security by producing knowledgeable managers and planners for the nation’s growth In 1890, Congress passed the second Morrill Act providing funds to support instruction in the colleges that the first Morrill Act established U.S. Department of Education • Established in 1867 • This brought the function of education to a leadership position in the federal government • Later, the Department was “downgraded” to the Office of Education. It continued as part of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare until reestablished as a Department in 1980 The 1917 Smith-Hughes Act During World War I, the government faced large numbers of returning soldiers who needed specific workplace skills This Act gave states grants to support vocational education States Administer Federal Monies • The national government directed the state’s role in administering this program according to federal standards and funds – a model followed in future federal education grants. 1918, Congress Passed the Vocational Rehabilitation Act Providing funds to rehabilitate World War I veterans. 1919, Congressional Act to Provide for Further Educational Facilities Authorized the federal government to sell surplus machine tools to schools for 15 percent of their original purchase price – enabling schools to have the equipment needed to give students “real world” training. 1920, Smith-Bankhead Act Authorized grants for the states to provide vocational rehabilitation programs. 1935, Agricultural Adjustment Act Congress and the Executive Branch desperately sought the quickfix to save the crashing economy and relieve citizens’ economic despair. Set up the School Lunch Act – providing food to schools so it could feed its students (because their families might not). 1941, Amendment to the Lanham Act of 1940 Providing federal aid for the construction, maintenance, and operation of schools located in federally impacted areas… (where U.S. military families lived and worked on government-owned land and facilities and paid no state or local property taxes). 1943, Vocational Rehabilitation Act • Public Law 78-16 • Provided assistance to disabled veterans returning home from WW II 1944, The G.I. Bill Servicemen’s Readjustment Act Provided education benefits to military returnees as they reentered civilian life By providing an attractive education alternative to employment, the GI Bill delayed many of the returning veterans from flooding the labor market and stalling economic recovery. G.I. Bill Offered a living stipend while veterans attended school, effectively transitioning the potential labor glut into a student cohort earning their living while learning new work knowledge and skills Enabled an educational investment in our country’s infrastructure by enhancing the workforce’s job skills G.I. Bill, cont. Effectively supplied a massive education infusion to citizens, raising the education bar, and expanding learning horizons, career, and lifestyle opportunities for these returnees and for future generations. Federal Property and Administrative Services Act Initially, schools and colleges felt a bit overwhelmed with the newfound demand for their services, placing a drain on resources. The Act allowed the national government to donate surplus federal property to educational institutions. After WWII America believed herself to be the most powerful nation in military and economic strength. Following Sputnik in 1957, however, the nation faced a wrenching reality check. National Defense Education Act The NDEA provided economic assistance to states and individual school systems to “beef up” science and math instruction, foreign languages, and other crucial subjects. NDEA Also Supplied States with Resources Including • • • • • Statistical reporting Guidance & counseling Testing Vocational & technical programs Higher education student loans & fellowships • Foreign language study & training • New teaching media Education of Mentally Retarded Children Act Train teachers to work successfully with disabled students. Prior to this time, only a few states distributed funds to localities to supplement educational programs for handicapped students. Most families with disabled children had to find their own help. 1975 Education for All Handicapped Children Act Public Law 101-46 Intended the federal government to pay 40% of the funding necessary for special education services States & localities to pay the rest Today, the federal government pays 17% of special education costs instead of the 40% promised in national legislation 1965 Elementary and Secondary Education Act Categorical Aid Programs: Title I Provided supplemental school program grants for children of low-income families Intended to help economically disadvantaged students succeed (catch up with middle class and affluent peers) in the regular school program Provided additional educations resources to improve their basic and advanced skills to achieve gradelevel proficiency Included extra or school-wide activities encouraging heavy parent involvement Government Distributes These Funds in 2 Ways Basic Grants Flow through the State Education Agency (SEA) to localities based on a formula involving the school district’s number of eligible students and the average state perpupil expenditure. Concentration Grants Available only to restricted populations and represent a smaller percentage of the overall funding. Particularly useful to school systems with high percentages of disadvantaged students. Title I • Title I provided supplemental school program grants for children of low-income families • This program intended to help economically disadvantaged students succeed in the regular school program by improving basic and advanced skills and achieving gradelevel proficiency • The program could include supplemental or school-wide activities encouraging heavy parent involvement Title I, cont. • Most Title I funds are basic grants which flow through the State Education Agency (SEA) to localities based on a formula involving the school district’s number of eligible students and the average state per-pupil expenditure • Concentration grants represent a smaller percentage of the overall funding within this Title Title I, cont. • Concentration grants are designed for localities with a high number of eligible students – more than 6,500 students or more than 15% of all students eligible for Title I funding • This is particularly useful to school systems with high percentages of disadvantaged students Title I, cont. Annual amount of Congressional funds allocated for Title I varies from year to year, depending on political allocation decisions Requires that school divisions will not receive less than 85% of its previous year’s funding share Title I money had less buying power in the 1990’s although expected to support learning interventions for more children Title II Grant monies for school library resources, textbooks & other instructional materials, including audio-visual equipment Called the Dwight D. Eisenhower Mathematics & Science Education Act Title II Provides presidential awards for outstanding teaching Funds for magnet schools Monies for talented and gifted programs Funds for women’s educational equity Grants for drug abuse prevention, dropout prevention, bilingual education, & other programs. Other Categorical Grants Title III Provided funds for supplementary education centers and services to public and private schools Other Categorical Grants, cont. Title IV Allocated funds for regional educational research and training laboratories Other Categorical Grants, cont. Title V Provided funds for strengthening state departments of education (otherwise known as State Education Agencies – SEAs) Funding Public Broadcasting • In 1967, Congress passed the Public Broadcasting Act • The Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB) was created and assumed a major role in routing federal monies to noncommercial radio and television stations Funding Public Broadcasting • The CPB began program • Many of today’s new production groups and started Educational Television (ETV) networks • The CPB was responsible for awarding construction grants for educational radio and television facilities teachers were raised on programming given its start by the CPB. Those programs include Sesame Street, The Electric Company, and others. Educating Disabled Students • In 1968, the Handicapped Children’s Early Education Assistance Act, Public Law 90-576, was passed. This act provided for the authorization of preschool and early education programs for handicapped children Educating Disabled Students, cont. • Seven years later, in 1975, Public Law 94-142, the Education for All Handicapped Children Act provided that all handicapped children have a free, appropriate public education Social Changes & School Funding • In 1970, many federal legislative changes came into being that had their beginning in social changes of the times • The National Commission on School Finance was established under the Elementary and Secondary Education Assistance Programs, Extension, Public Law 91-230 Social Changes & School Funding, cont. • Office of Education Appropriation Act, Public Law 91-380, provided emergency school assistance to desegregating local school districts and schools • The Drug Abuse Education Act of 1970, Public Law 91-527, provided funding for the development, demonstration, and evaluation of materials dealing with the many problems of drug abuse Selected Other Federal Funding • In 1986, the Handicapped Children’s Protection Act, Public Law 99-372, was passed • This allowed parents of handicapped students to collect the attorney fees in cases brought under the Education of the Handicapped Act Selected Other Federal Funding, cont. • In 1993 the NAEP Assessment Authorization, Public Law 103-33, authorized the use of the National Assessment of Educational Progress, the Nation’s Report Card • To be used for the purpose of making state-bystate comparisons of student performance. Country-by-country comparisons had already been made public Selected Other Federal Funding, cont. • In 1996, Congress felt pressure from states and localities regarding legislation that required states and localities to take certain actions that required money without the financial provisions in the acts to cover costs • To that end, the Contract With America: Unfunded Mandates, Public Law 104-4, was passed in an attempt to curb the practice of imposing unfounded federal mandates on states and localities Federal Funding Today • Today, the federal government funds approximately $50 billion dollars for education purposes at the elementary and secondary levels Federal Funding Today, cont. • The federal government has invested more than $1 trillion in elementary & secondary education from 1969 to 2001 – an average of more than $27.7 billion per year.