Paradise Lost: Satan and Eve (2011)

advertisement

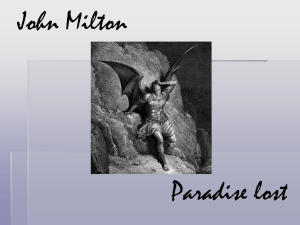

Robert Townsned British Literature 301 April 27, 2011 Paradise Lost: Satan and Eve’s Unlikely Connection In Paradise Lost, author John Milton uses the story of the Fall of Man from the Old Testament to create an epic poem that analyzes and criticizes controversial topics ranging from the current political climate of England to the conflict of free will and God’s authority. Because essentially everyone in England during that time were Christian or at least knew the Bible, the basic plot was and remains fairly simple and easy to follow for the reader. While Milton’s story does stay true to most of the Biblical story, his addition of new characterizations for each main figure and more background information leads to an ability to ponder Christian beliefs, but not sound overly offensive to the Church. One of the best examples of Milton’s use of these stock characters and plot points to formulate entirely new ideas, as well as disparage established views, was found in Book IX. Adam and Eve got in to an argument, ending in the tragic decision that sealed the couple’s fate of losing Paradise for all of mankind. Within this argument, a very important part of Milton’s analysis of human existence is brought to the forefront. This less conspicuous, but very controversial, challenge to the Christian faith was his contemplation of if humans have free will, or if God is really in control. Milton makes no direct conclusions, but the question is everpresent, and many of the actions surrounding the Fall of Man, as well as the conversations regarding it, keeps the audience constantly questioning if God should have participated more, if He should have done less, and how much God is tinkering in our lives today. Milton forces the audience to contrast their established views of God and the Son with his new, more contentious, view of them throughout Paradise Lost. During the poem, it becomes apparent that everything outside of Adam and Eve’s control leading up to their work discussion could have been stopped by God at multiple times. Within the actual chronology of Paradise Lost, Satan and the fallen angels established the initial challenge to God’s authority pervading their free will. Satan argued that if angels truly did have free will, it was “flatly unjust, to bind with law the free” (5.818), and it was completely unacceptable for God to have made his Son and given him more power than the angels who were supposed to be nearly equal God before the Son came. This logic that being completely free shouldn’t have catches or caveats was certainly convincing enough to gather a large amount of Heaven’s angels. The way that this argument is displayed, under the pretenses that Satan is almost a character whom the reader feels sorry for, presents a challenge for the readers to seriously consider the extent to which Satan’s point is and is not correct. Satan’s case of free will being without restriction directly put Eve’s decisions to work alone from Adam and to eat from the Tree in a different perspective as well. If she had free will, any kind of test or rule such as not eating from a single tree would be overstepping that free will, according to Satan. However, Abdiel, the one fallen angel who decided to return to God, supplies the audience with a counterpoint to Satan’s convincing argument. Because God is the sole creator of everything, and “God and nature bid the same,” (6.176), only God himself can determine what free will, along with any other “natural” right or privilege, means. Therefore, if God says that liberty means one can do anything as long as they stay true to God’s word, that is what liberty means, and no one can change that. When Satan creates his definition of free will that he believes his companions should accept, by Abdiel’s reasoning, Satan is doing the exact same thing that he was adamantly against God doing, by creating his rules and trying to make others comply. Through giving this just as strong counter argument to Satan’s comments on free will, Milton maintained a somewhat neutral tone during this debate, while still forcing the audience to actually think about such a complicated yet little discussed theological topic. The first time God shows his knowledge of what’s to come within the epic poem is in Book III, where, as Milton writes, “God beholding his prospect high, wherein past, present, future he beholds,” (3.76-7), which is the point when God first fully recognizes the fact that Satan will succeed in tempting Man into sin. However, instead of creating plans to stop Satan from making Adam and Eve sin, God decides to allow the couple to choose their own fate, which will inevitably be the wrong choice, and begins planning how he will bring the human race back to salvation eventually. Even though God knows all attempts will be in vain, he still attempts to intervene through the angel Raphael, who informs Adam about the danger Satan poses. When Adam tries to convince Eve that God was strongly against them splitting up during the Book IX debate, God could have spoken to them himself and told Eve about how working alone would doom them. However, God tells his Son that he genuinely wants both his angels and humans to have free will, for if they were “not free, what proof could they have giv’n sincere of true allegiance?” (3.103-4). In other words, God was willing to accept the inevitable betrayals both by man and fallen angels because he wanted to allow those who were pure in spirit to love God and fellow creatures from their own heart, not because they were simply forced to do so. Because of this desire, Eve’s tragic decision to leave Adam and work by herself was watched and accepted by God, thus confirming her free will. However, when Satan eventually succeeds, the reader is left to question if God should have done something more than he did, or whether or not his lack of intrusion was actually maintaining the belief of free will regardless due to his all-knowing nature being present regardless. Even though in Books III and IX, God shows his strong desire to maintain man’s free will and allow Adam and Eve to determine their fate even if it ends in damnation, there are a number of instances where he greatly contradicts his own belief of allowing free will (besides the established rules). From nearly the second that Eve becomes conscious, God seems to be disregarding her freedom of choice. In Book IV, Eve explains her story to Adam of how she came to him the day she was created. Two separate times, she admits that she would not have been with Adam, at least immediately, if it was not for God’s insistence. The first time occurred while she was admiring the friendliness of her own reflection, a reflection which “I had fixt mine eyes till now… had not a voice thus warn’d me,” (4.466-8). God had to push her towards Adam on a second occasion, when she first saw him and is greatly unimpressed. Even though Adam considered Eve as below two higher authorities, calling her “daughter of God and man” (9.292), clearly she did not see it that way at first. Instead, she was directed and informed by God where she was meant to go and who she was meant to be. After having essentially no say in what she did from the moment she was self-aware, Eve had rarely felt the free will that she and Adam were supposed to be granted by God. During the argument about working together or alone, Eve is finally asserting her own reason, the essential attribute to a free mind. However, Adam essentially disregards this at first by ironically stating “reason He made right,” (9.351), in an attempt to argue that his own belief (that they should stick together) is the correct, or superior, reasoning in this situation. By the time Adam begins to yet again attempt to almost claim a Godly right to control her choice, the audience is almost compelled to support her desire to finally experience this free will that an equal of Adam should have been given, even while being fully aware of the consequences. Tragically, when Eve is finally able to do one thing that was actually of her choosing, she ends up going one choice to far. While it is clear that God wanted to give his new creations autonomy, Adam and Eve’s seemingly lack of actual choice of fate brings about even more conflicting evidence of whether free will is an actual fact, or if Adam and Eve, along with all others, were simply puppets of God. John Milton’s Paradise Lost brilliantly combines a familiar and extremely significant Biblical story with novel background information and characterization of the main figures to create a poem that is able to both maintain an interesting storyline while making the reader seriously consider the deep concept of what free will really means. In the extended discussion between the seemingly oppressed Eve and superior Adam in Book IX, Milton was able to exemplify one last time the question of whether God had done too much and overstepped the human’s free will, or not enough. This theme was a unifying one throughout the novel, beginning with the initial fight in Heaven, where Satan desired to leave God because he felt God was robbing the angels of their rights to liberty. From this point on, the contradiction of free will and God’s all-knowing and all-powerful nature affected every single action that led up to the final tempting of Eve. While John Milton ends the novel without any closure to this continuously important theme, his unique challenge of the accepted ideas of free will and countless other topics in Christianity has been one powerful factor in Paradise Lost still being commonly considered as one of the greatest stories ever written, over 300 years later.