PPTX

advertisement

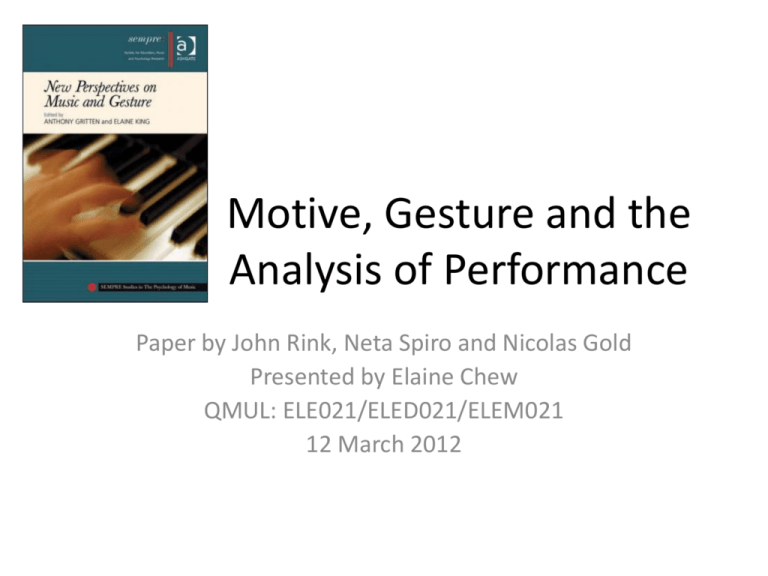

Motive, Gesture and the Analysis of Performance Paper by John Rink, Neta Spiro and Nicolas Gold Presented by Elaine Chew QMUL: ELE021/ELED021/ELEM021 12 March 2012 Gestures • music’s gestural properties are neither captured by nor fully encoded within musical notation, but instead require the agency of performance to achieve their full realization. • gestures created in and through performance potentially have motivic functions. • Such ‘motives’ are defined as expressive patterns in timing, dynamics, articulation, timbre etc that maintain their identity upon repetition. Motives • Definition: short musical idea, melodic, harmonic, rhythmic or combination thereof. • A motif is most commonly regarded as the shortest subdivision of a theme/phrase that still maintains its identity as an idea. Structure and Performance • Relationship between musical structure and performance is complex and non-exclusive. • One must acknowledge the origin and dynamic nature of music structure. • Performers create musical structures/shapes in every performance. • The dynamic structures underlying and genera ted within performed music potentially operat e at numerous hierarchical levels. Goal • Determine how the sounded music is made to cohere; focus not the intent of the performer. • Trap of traditional analyses: assembling data and ignoring broader musical purpose/effect. • Study couples objective analytical methodology with (subjective) critical assessment. cevaplar.mynet.com/soru-cevap/mazurka-hangi-ulkenin-milli-dansidir/135666 Chopin’s Mazurkas • Urbanized Mazurka tradition • Traces of at least three folk dances – oberek (lively), mazur (joyous) and kujawiak (plaintive) • Modal (Lydian Fourth) elements, tendency towards chromaticism • Folk devices: drone fifths, ‘tight’ ornamentation, obsessive repetition, 2nd/3rd beat accents (stamping gesture in dance), waltzlike accompaniment theuniversallanguageofmusicic.wordpress.com Mazurka Op. 24 No. 2 • Composed 1833, published 1835 • Mazurkas not for dancing (letter to family) • Example: Arthur Rubinstein – http://www.youtube.com/watch?v =vzxlN_lDvv0 Mazurka Op.24 No.2 Mazurka Op.24 No.2 mazurinspired RH melody aching melancholy of kajuwiak ebulient mazurlike phase Musical Process • Process from note to note, bar to bar, phrase to phrase, while also involving overarching relationships between less proximate features • Gravitational tendencies of sections: processive or recessive, prospective or retrospective • How non-symmetrical middle section is handled against symmetrical first part, and non-symmetrical foreshortened reprise Time • Discrepancy between metronome markings: crotchet=108/192 • Types of rubato (e.g. at bar 29) – Structured temporal flexibility – Freer, with irregular beat lengths – At the level of form • Synchrony / assynchrony between two hands • Timing of ornamentation (on/before beat) Beat Length in All 29 Performances Self Organizing Maps Clusters similar timing/dynamic patterns T1 32%, T2 30%, T3 24%, T4 14% D1 32%, D2 30%, D3 24%, D4 14% almost flat expected mazurka pattern phrase final lengthening typical triple meter Distribution of Timing Clusters Distribution of Dynamic Clusters Distribution of Timing Clusters within each performance Broad Patterns and Individual Performances • Broad comparisons reveal patterns across large number of performances • Detailed examination of individual performance required for insights into patterns distinctive to each performer • SOM trained on individual performances to reveal inter- and intra-performer patterns and distributions Chiu Timing Clusters Least number of timing clusters, 3 ~ perceived richness and interest Chiu Dynamic Clusters Magaloff Timing Clusters Highest number of timing clusters, 18 few patterns return when material repeated patterns form sub-groups Magaloff Dynamic Clusters Rubinstein Timing Clusters Middling number of timing clusters, 8 considerable alignment between repeated thematic material and expressive pattern Rubinstein Dynamic Clusters Three questions • Musical meaning and significance of analytical findings? • How do expressive patterns give musical coherence? • How to understand hierarchy of temporally defined musical gestures? Notes • Number of cluster types not directly related to perceived richness and interest • Chiu (3) sounds mechanical • Magaloff (18) sounds willful and unstable • Rubinstein (8) balances rhythmic consistency with rubato in melodic line • Not presence or quantity of expressive clusters, but what performers make of them that counts Rubinstein Beat Lengths Broad tempos act as background to / foundation for more immediate temporal fluctuations Rubinstein: Timing Clusters vs. Structure of Piece Hypermeasure = 4-bar unit RT3 / RT7 feature agogic accents on first downbeat Used in 23 or 30 hypermeasure starts Temporal Shape of Rubinstein’s Performance regularity This image helps us understand what we are listening to but possibly unable to hear. Reference • Rink, John, Neta Spiro, and Nicolas Gold (2011). Motive, Gesture and the Analysis of Performance. In New Perspectives on Music and Gesture, Chapter 13: 267-292.