Mobile Assignment

advertisement

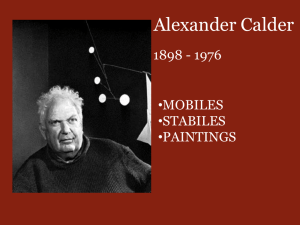

From the Artist: How to Make a Real Mobile BY Marc Mahler Name ____________________________ Date _____________________________ Period ___________________________ Wondering what these things are you’re looking at? They are mobiles, as in art, a type of sculpture based on balance and characterized by the ability to move when propelled by air currents, by touch, or by a small motor at any one time. The most striking feature of the mobile is that, unlike traditional sculpture, it achieves its artistic effect through movement; it is the most familiar form of kinetic art, which requires movement of some kind. A typical mobile consists of a group of shapes, frequently abstract, that are connected by wires, string (often nylon thread), metal rods, hollow aluminum tubes, swivels or the like. The shapes are usually made of sheet metal, wood, plastic, glass, acrylic glass (plexi-glass), foam, paper, or aluminum honeycomb panels. Although mobiles are usually suspended (often hanging from a ceiling), some are designed to stand on the ground or a platform, and are sometimes mistakenly labeled as “stabiles”. Stabiles, a term coined by Jean Arp, are large scale stationary abstract sculptures developed by Alexander Calder, usually made of bolted metal plates, that have contributed significantly to the concept of public art. All mobiles, hanging or standing, are a genre of kinetic sculptures, the term “kinetic” meaning “moving” or “in motion”. Suspended kinetic sculptures have probably been around since prehistoric times in the form of wind chimes. Evidence of them has been found that proves they existed in ancient China, Japan and Rome. There are traditional mobiles made of straw called “Himmeli” from Finland and Sweden and I’ve come across a mobile made in 1751. The Russian artists Naum Gabo, Aleksandr Rodchenko and Vladimir Tatlin are credited with experimenting with hanging kinetic sculptures as an art form first in the late 1910s. Man Ray made the first mobile out of coat hangers in 1920 that’s based on the whippletree mechanism. He also experimented with hanging abstract pieces of sheet metal. Bruno Munari started to create is own early version of mobiles in the late 1920s which he called “Useless Machines”. However, mobiles, the way we know them today as a modern art form, were mostly developed by the American sculptor Alexander Calder (influenced by the abstract work of Piet Mondrian, Joan Miró and Sophie Taeuber-Arp) beginning in the 1930s. In a 1962 interview he said: “The mobiles started when I went to see Mondrian [in October 1930]. I was impressed by several colored rectangles he had on the wall. Shortly after that I made some mobiles; Mondrian claimed his paintings were faster than my mobiles.” The name “mobile”, a French pun meaning both “mobile” and “motive”, was given to them by the artist Marcel Duchamp, a friend of Calder’s, although he apparently already used the term in 1913 for his readymade Bicycle Wheel, which some consider to be the first kinetic sculpture. It’s all in the balancing points: Marc Mahler shows how to create a Calder-inspired installation of your own. Ever since I came across Alexander Calder‘s mobiles at the National Gallery of Art fourteen years ago, I’ve been fascinated with mobiles. At first I tried my hand at minimalistic wire mobiles. After receiving several requests for larger custom mobiles, what started as a hobby turned into a full-time occupation. Since then, I’ve designed and made a wide variety of retail mobiles, large custom mobiles, and kinetic sculptures. I’d like to explain how to make a real mobile. By a “real” mobile, I mean one in which the balance of the different parts depends on those parts, which results in much more interesting dynamics than if you just tie a number of objects to a coat hanger or a horizontal circle. I’d like to provide you with a sort of blueprint for mobiles. Once you have that, you can apply it using any materials, whether those are just some random objects you find around your house, objects specific to a season or a holiday, or some midcentury modern shapes. Here’s the first thing to consider: There’s a balance point and a center of the mass (weight) of the object. If the center of mass of the object is above the balance point (meaning the majority of the weight is above the balance point), the object will fall over. If the center of mass of the object is below the balance point, it will balance. The farther below the balance point the center of mass is, the more stable is the balance. So by making the parts of a mobile curved downwards, you lower the center of mass, and therefore making it more stable and easier to balance. Part A weighs the same as part B – Balance point is right in the middle: Part A weighs more than part B – Balance point moves closer to part A, the heavier part: The following illustration might look complex, but it’s really the exact same idea. All those lower parts count as just one part when it comes to the balance of the top part, it’s only about the balance between part A and part B: The trick is that you build the mobile from bottom to top. Find the balance point between the bottom two elements. Then you add the next element on top of that and find the balance point between the new element and the first two elements and so on. Don’t weigh the parts or anything to make sure it balances. Just find the point by balancing it on your finger, or if you want to be exact, tie a string around it and move it back and forth until it balances. Anything goes from here. Use whatever you want for weights or to connect the pieces. The possibilities are infinite. http://www.marcomahler.com/how-to-makemobiles/ Mobile Assignment o A few suggestions: use odd numbers, keep things off balance. o remember that warm colors (red, orange. yellow) advance and cool colors recede. o consider using the rule of thirds (divide the space, or pieces into groups-2/3 one color, about 2/3 of the rest a second color and the remaining section a third color). o If you want to see some of these principles in action or just explore Calder’s art, look at this great site with a huge catalog of his work. 1. Design and construct a mobile that is suspended from a base. 2. Begin by designing and building the base from poster board. The simplest type is a folded base like shown in the mobile at the top of the page. You can use 2, 3, or 4 pieces to make the base. Multiple pieces may be stapled, glued, or tab and slotted together Look at Calder’s examples for inspiration. 3. Decide the balancing shapes and colors. Cut these form poster board. Determine the balancing point and then make a hole with a pushpin. 4. Cut and bend fine wire to make loops for each shape. Thread each poster board shape onto a loop. 5. Beginning with the bottom piece, make a small round loop at the ends of the wire. Attach a shape to each end. 6. Determine the balancing point on the wire and make a loop. 7. Attach the next shape to the second wire and to the loop in the first wire. 8. Add a counter balance shape on a longer wire that will balance the movable shape onto the base. 9. Find the balancing point and attach the mobile to the base. 10. Pieces may be colored using marker before the final assembly.