Opening Statement NUIG 02-12-2014

advertisement

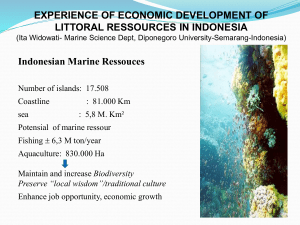

Developing the seaweed industry in Ireland including the feasibility of developing seaweed farms Thank you for the opportunity to make a statement on behalf of the Irish Seaweed Research Group (ISRG) at NUI Galway. NUI Galway has a long history of seaweed research and currently there are several active groups in the University with interests in areas including seaweed ecophysiology, biomass conversion, bioremediation, functional foods, ecosystem effects, biodiversity and conservation. The work of the ISRG likely to be most relevant to the committee relates to seaweed biomass assessments and aquaculture. Recent projects of note are the seaweed hatchery project coordinated by BIM1, Enalgae2 and MacroAlgaeBiorefinery3 (MAB3) projects. Work in Ireland on these projects has generally focussed on refining techniques for cultivating species and estimating likely yields from aquaculture. Other European countries scaling up their research in the use of seaweeds are Denmark, Scotland and Holland to add to the pre-existing centres in Norway, France and Spain. There are three main headings that we would like to summarise information under before drawing some conclusions based on the group’s experience: 1. Status of the seaweed industry and the Irish dimension 2. Issues at the scale of individual farms 3. Wider issues relating to seaweed aquaculture and harvesting 1. Status of the seaweed industry and the Irish dimension According to recent figures from the FAO4 (2012), 19 million tonnes of seaweed were produced worldwide, the vast majority of which (96%) is produced by aquaculture. This makes seaweed the second largest global production after fresh water fish (by weight). The value of the seaweed harvest was estimated at €4.6 billion ($5.7 billion) in 2010. Uses for seaweeds are varied, but the most common uses are as a human food (majority of the production) or as raw material for phycocolloids (collective term for gels extracted from seaweeds known as agar, alginate and carrageenan). They are also used as a fertiliser and soil conditioner, as well as a dietary supplement for animals. Contrary to the global situation, Irish seaweed production is predominantly hand-harvested from wild resources, and mostly from the western/northern coasts. A handful of species have traditionally been harvested, with most of the production from cutting Ascophyllum nodosum (feamainn bhuí; egg wrack), ~25000-30000 wet tonnes. Others include Palmaria palmata (Creannach, dillisk), ~30 wet tonnes Laminaria digitata (coirleach; oar weed), ~200 wet tonnes, and maërl, 8000 wet tonnes (although Irish harvests stopped several years ago). 1 PBA/ SW/07/001 (01), ‘Development and demonstration of viable hatchery and ongrowing methodologies for seaweed species with identified commercial potential’. This project was carried out under the Sea Change Strategy with the support of the Marine Institute and the Marine Research Sub-programme of the National Development Plan, 2007-2013. 2 EU Interreg IVB NWE funded, details at http://www.enalgae.eu/ 3 Danish council for strategic research funded, details at http://www.mab3.dk/ 4 FAO (2012) Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The state of the world fisheries and aquaculture 2012. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Department. Rome. FAO 209 pp 1 Aquaculture of a select few species does exist in Ireland, however much of the work to date has been at the research or pilot scale level. Several commercial seaweed farms have developed over the last 2-4 years, and with tonnages of between 50-90 wet tonnes per year of the kelps Alaria esculenta and Saccharina latissima. According the latest statistics we have from BIM, there are currently 7 existing seaweed aquaculture licenses, with a further 23 applied for. Irish seaweed is either exported mainly to China for alginate extraction or used as a soil conditioner/fertiliser (Ascophyllum nodosum), and used by small-medium sized Irish enterprises for production of cosmetics and thallasotherapy, human food, plant growth stimulants and soil conditioners, as well as livestock and pet food supplements. According to a study carried out by Morrissey et al.5, the seaweed and biotechnology sector is worth €18 million per annum and employs 185 full time equivalent people. An inexhaustive list of Irish companies involved in developing and marketing higher value uses include: BioAtlantis (plant growth stimulants and animal nutrition products) Brandon Products (plant growth stimulants) Voya (cosmetics and thallasotherapy) Irish Atlantic Seaweed (pet food supplement) LoTide (human food) Wild Irish Sea Veg (human food) 2. Issues at the scale of individual farms The BIM seaweed hatchery project looked into the feasibility of seaweed aquaculture for the production of kelp species such as Laminaria digitata. The three year break-even price ranged between €1.12 to €2.15 per fresh kilogram of cultured seaweed, depending on whether or not seaweed was co-cultured with scallops to form a secondary revenue stream, and whether the seaweeds were grown re-using old mussel longlines. The BIM study was an attempt to understand the viability of seaweed aquaculture through one collaborative project. It is difficult, however, to generalize about the likely sizes of future farms, when successful economic models for Western Europe are not yet widely established. Therefore the economic analyses that began in the BIM study and are currently being refined by the EnAlgae project (and soon ready for public release) and will represent updated European estimates. We hear that the speed of procesing licensing applications is considered to be an issue for seaweed farmers. Our understanding is that seaweed farming is considered alongside other forms of aquaculture and that the system is not yet clearly differentiating between animal and algal aquaculture, despite the different potential impacts. While in general the seaweed industry has become somewhat modernised with new developing and higher value products, seaweed 5 Morrissey K., O’Donoghue C., Hynes S. Quantifying the value of multi-sectoral marine commercial activity in Ireland. 2011. Marine Policy 35 721-727. 2 aquaculture is still a niche industry, the growth of which would benefit primarily from the efficient granting of new licenses, enabling a critical mass of producers to develop. Realistically a seaweed farm is likely to be unsustainable if coupled to a bulk market (e.g., milled seaweed or alginate). Such markets are subject to global price variations and strong competition from countries that can harvest at lower costs. A number of reports recognize the importance of developing high value products. There is an example of this for a seaweed species that grows in Ireland: Acadian Seaplants have developed a market for colour varieties of Chondrus crispus cultivated in a land-based tank system in Charlesville, Nova Scotia6 (sold as Hana-Tsunomata™). 3. Wider issues relating to seaweed aquaculture and harvesting The existing Irish harvests, primarily of Ascophyllum nodosum, appear to have been sustainable. Expansion to very large scale wild harvesting of Ascophyllum or other species may not be sustainable and is likely to have ecosystem impacts, particularly where the algal production would otherwise be transferred to important fish, shellfish or bird species. These sorts of subsidies are not well understood. As many potential harvest areas are protected under the EU Habitats directive, the need for appropriate assessments and the precautionary principle may limit the scope for licensing extensive harvesting. In comparison to some fish aquaculture, seaweed aquaculture currently has a relatively benign image. The ecosystem impacts of seaweed aquaculture are the subject of investigation within the group. As growing algae take up nutrients, they may reduce issues related to excess fertilization of coastal waters (eutrophication). Seaweed farms may provide additional habitat for species, including nursery areas for fish. Seaweeds are grazed by invertebrates and supply dissolved and particulate organic material to the adjacent system. This may boost the local productivity of an area. The ecosystem roles of farmed seaweeds have already been raised in the context of what is known as Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture (IMTA): the idea that growing a mix of species in close proximity provides a synergy that has may reduce the environmental impact of traditional forms of aquaculture, such as finfish production while providing additional sources of revenue for the farmer. For example, salmon excrete nutrients that are taken up by seaweeds, with particulates from salmon cages and seaweeds sustaining invertebrates like mussels. Conclusions The scientific consensus is that the sustainable future for seaweed harvesting and aquaculture is to have new, high value products. This may be possible with a single product (e.g. the product HanaTsunomata™), but in many cases may require a diversity of income sources from each harvest. Sometimes this is referred to as a biorefinery concept: where a series of high value products are extracted from the source material. Reaching the goal of a product or products from seaweed requires teams working across the value chain, including investment in developing the markets for products. The potentially long lead-in to generating profit makes this proposition difficult for small businesses. Developing markets is 6 http://www.acadianseaplants.com/marine-plant-seaweed-manufacturers/quality 3 generally not something that universities do, or are funded to do. The nature of funding tends to focus research on problems in specific fields. More broadly, there are issues in sustaining capacity and knowhow in areas like aquaculture research. Funding for activities like new species development is limited and instruments like the Societal Challenges pillar of Horizon 2020 are more focussed on policy issues7. We feel that it is important to have funding that integrates research teams and industry, but have not found that the existing models are particularly accessible to the development of new products, particularly where this contains an element of risk and the likely industrial partners have little scope to make long term investments. A potential initiative could be activities that bring the members of the research and commercial community together. This could include facilities that are established on a cooperative basis (e.g., drying halls, processing equipment etc.). An approach slightly broader than a trade association may be useful. There is a model in the UK that seeks to generally raise the awareness of seaweed for health while raising the profile of member’s products (Seaweed Health Foundation8). A similar initiative may be possible in Ireland, recognizing that participation may require a bottom-up approach and that any financial costs of membership should not be so high as to exclude small or new businesses. 7 For example, next year’s call H2020-SFS-2015-2 ‘Consolidating the environmental sustainability of European aquaculture’ 8 http://www.seaweedhealthfoundation.org.uk 4