Ethics, Governance & SustaInable development

advertisement

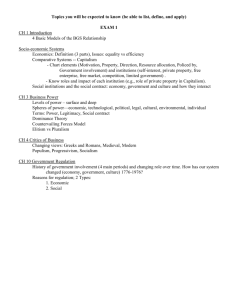

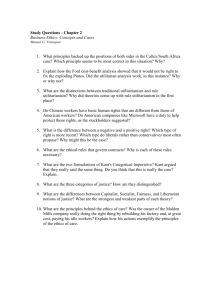

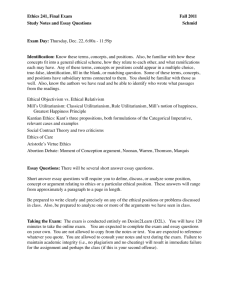

Practical Notes for a Practical Class and a Practical Exam Ethics (in philosophy) embraces the study and the evaluation of human conduct in the light of moral principles. Moral principles may be viewed either as standards of conduct that individuals and groups have constructed for themselves, some set of principles written into the fabric of the universe, or the body of obligations and duties that a particular society requires of its members. In short, as our mothers and fathers taught us – ethics is largely about knowing the difference between right and wrong. We identified four primary schools of ethical thought: (1) Utilitarianism (2) Deontology; (3) Aristotelian Ethics and Practical Wisdom; (4) Ubuntu & Communitarianism We discovered that ethical problems are often quite complex and do not yield to simple solutions. If they did, then we would always be in agreement about what the correct course of action is with respect to a given problem. We also saw (in Antigone) that various kinds of ethical claims might apply in a particular situation – but pull us in different directions. Is there such a thing as ‘expert judgment’ about the genuineness of expressions of feeling? Even here, there are those whose judgment is ‘better’ and those whose judgment is ‘worse’. Corrector prognoses will generally issue from the judgments of those with better knowledge of mankind. Can one learn this knowledge? Yes; some can. Not, however, by taking a course in it, but through experience. Can someone else be a man’s teacher in this? Certainly. From time to time, he gives him the right tip. – This is what ‘learning’ and ‘teaching’ are like here. – What one learns here is not a technique; one learns correct judgments. There are also rules, but they do not form a system, and only experienced people can apply them right. Unlike calculating rules. What is most difficult here is to put this indefiniteness, correctly and unfalsified, into words. L Wittgenstein Philosophical Investigations, II, xi (1946) Individuals are ends in themselves. Whereas utilitarianism emphasizes the greater good, deontological ethics emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individuals must be treated as ends, and never SOLELY as a means. Every individual act must be capable of being universalizable. For example, Kant writes that one can never lie since that would undermine our commitment to truth-telling and the commitment to living in a manner that accords with respect for other individuals and our ability arrive – through reason to ‘the moral law’. Is it always possible to treat a person as an end in herself or himself ? Is the criterion for universalizability too strict? If you had Anne Frank hiding in the attic, and the Nazis were pounding at the door searching for Jews, would you tell the truth (for truth’s sake) or would you lie? And would your lie destroy the commitment to truth-telling as a general ethical norm? Does Kant have a larger point when he makes universalizability so important? What is he trying to tell us about ethical behaviour? The moral worth of actions or practices is determined by its consequences. Generally, individual acts are judged by their ability to increase the general happiness of (or overall utility for) the entire commonweal – and not the individual. Two kinds of utilitarianism: Act Utilitarianism Rule Utilitarianism Critics suggest that if you made the great possible utility or happiness the measure of all acts, individual or collective, you could justify the sacrifice of individuals to the overall good of the community. Is that true? Peter Singer points us in a different direction Singer’s utilitarianism to demand that we submerge our individual (and partially collective) happiness when confronted with the morally compelling and urgent needs of others. Does Act Utilitarianism look more or less dangerous than Rule Utilitarianism? Why? Does Rule Utilitarianism really always collapse into Act Utilitarianism? Aristotle speaks of practical wisdom when he considers what it means to lead a virtuous life. By practical wisdom, he means several things: We can rely on the insights of virtuous individuals who came before us. Ethics requires us to work through a problem with some awareness of competing concerns. It is not, like other ethical approaches, grounded in unchanging first principles. ‘Practical wisdom’ might assist you in a business environment because it takes concrete situations seriously. Is Aristotle’s individual virtue consistent with how most people think about ethics today? How is it different from ‘leadership’? Some members of the Constitutional Court found the death penalty repugnant because retribution and group catharsis as the bases for punishment are inconsistent with an uBuntubased ethic of reconciliation, restorative justice and democratic solidarity. What limits, if any, can you identify with uBuntu or communitarianism as a departure point for ethics in a business environment? While different ethical positions will suggest different outcomes with respect to the same situation, those differences do not mean some answers are not better than others. Ethics requires us to offer reasons – and not selfserving reasons – for the decisions we take. Businesses are often confronted by ethical dilemmas. As the Tikkun Case Study suggested, a principled ethical approach can yield a solution to a problem that might otherwise threaten the existence of the firm. Ethics thus has a role to play in mediating disputes within a firm. When we speak of ‘the moral salience of everyday life’ in South Africa, it means that we are regularly confronted with choices about the correct course of conduct: how ought we to engage people who are substantially poorer than we are or who are from quite different, and often historically disadvantaged, backgrounds? This class asks you to consider whether a businesses can survive when half the country is unemployed and half the country experiences hunger. Sustainability – in various forms – is ultimately concerned with your companies survival, and that means taking account of and responsibility for the environment in which you operate and which you construct. ‘[I]f it is in our power to prevent something bad from happening, without thereby sacrificing anything of comparable moral importance, we ought, morally, to do it. By "without sacrificing anything of comparable moral importance" I mean without causing anything else comparably bad to happen, or doing something that is wrong in itself, or failing to promote some moral good, comparable in significance to the bad thing that we can prevent. What are the virtues and problems with this strong account of utilitarianism? (Virtue: low relative cost; Problem: proximity and connection) Adam Smith’s ‘theory of the invisible hand’ – on his own philosophical and political account – required more than price mechanisms to make the effective and efficient. It requires (today) such visible public goods as viable roads or trains or planes or shipping lanes; security of the person and property; firms and a workforce sufficiently educated to use the price mechanism to make sophisticated judgments about how best to employ their capital and their energy. In The Theory of Moral Sentiments, we saw that Adam Smith articulated a vision of social relations in which no economy, let alone a capitalist economy, could get off the ground unless it was underpinned by a community in which most citizens placed a significant degree of trust, faith, loyalty, and confidence in their fellow citizens. We require bonding networks and foundational institutions that inspire trust and mutual respect, so that we can carry out the instrumental acts that we engage in through the market. Kofi Annan’s vision for the UN Global Compact is predicated on similar principles of trust, loyalty, mutual respect, and compassion. That is, a global economy could not survive unless we saw our neighbours and citizens from other lands as worthy of mutual respect and recognizable as ends in themselves. The UNGC’s 10 principles emphasizes universal human rights, non-complicity in abuses, labour rights, environmental protection and anticorruption. The UNGC’s Decalogue is rather abstract and remains voluntary. However, the 10 principles themselves are drawn from UN documents (that applied to state action) that range between 60 and 40 years old. Only the application to companies and firms – and horizontal relationships with other natural and juristic persons – is dramatically new. We saw that while some principles might conflict – especially in weak-governance zones – those companies (Pharmakina & VCP) able to secure better relations with both the communities within which they operated and the state earned social licenses to operate. Businesses should 1. Protect internationally proclaimed rights 2. Ensure non-complicity in human rights abuses 3. Uphold freedom of association & collective bargaining 4. Eliminate Forced Labour 5. Abolish Child Labour 6. Eliminate employment discrimination 7. Support environmental protection 8. Promote greater environemental responsibility 9. Encourage development of environmentally friendly technology. 10. Work against corruption (ie, bribery) We have seen businesses like Pharmakina, VCP or BP try to make good on the UN Global Compact: and do so to a greater or a lesser degree: VCP far more, BP far less. But even those companies that seem to satisfy most of the UNGC tend to struggle in low governance zones or when the product that forms the core of their business damages the environment or is based upon practices that have historically impaired human rights. Low governance zones or ‘dirty businesses’ invite contradictions within the UNGC’s Decalogue. Why? What does the collapse of Lehman Brothers, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the Irish, Icelandic, Spanish & Greek economies, and behaviour of Goldman Sachs, say about ‘ethics’ in business? Should greater emphasis be placed on ethical behaviour in the marketplace? Is voluntarism likely to motivate firms to alter their practices? Should we instead look to put in place more stringent legal requirements for lending, borrowing and speculative trading in the marketplace? The Glass-Steagall Rule (US 1930s) barred commercial banks from taking on excessive risk. FICA -- RSA’s attempt to limit loans banks could offer by determining who qualified as a creditworthy client – has largely protected South Africa from the global meltdown. “AIG, Bear Sterns, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac needed government bailouts to survive. Lehman Brothers is in bankruptcy. Merrill Lynch has been sold. The shocking meltdowns signals a massive governance failure… that ignored or failed to see the level of risk their companies were taking on in a crusade to enhance results and their own compensation.” Wharton School, 2008 The global meltdown must lead one to be skeptical, at the very least, of the proposition that voluntary compliance with good governance codes are better than, or more effective, than enforcement of good governance standards subject to strict statutory or legal compliance. “South African corporate governance has been too aggressive in trying to lay down rules for every situation. Entrepreneurs are people who do things their own way. You cannot mould them. They have their own rules, their own motivation and culture. Their logic is different. It is really a matter of thinking differently to other people.” 26 Who believes that last statement? Is that claim any different than the claim that ‘the party must be the vanguard of the proletariat’? Have entrepreneurs been more or less successful in preventing meltdowns due to poor corporate governance? ‘There is one and only one social responsibility of business – to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say it engages in open and free competition without deception or fraud.’ • • Is this statement true? If so, on what grounds? Or do you think that not only does it fail as an ethical/legal thesis (when tested against most accepted ethical frameworks) but that it is internally or logically inconsistent? System by which Companies are Directed and Controlled Process by which Companies are made responsive to the Rights and Wishes of Stakeholders System of Principles and Practices by which the Enterprise Directs and Controls Accountability and Responsibility in terms of Power and Authority for the Sustainable Performance of the Enterprise and for the Benefit of its Stakeholders and the broader Community Board chairman independent non-executive director (or Lead independent non-executive director (LID)) Majority of non-executive directors Majority of non-executive directors independent Minimum two executive directors (CEO & CFO) Non-executive directors no share options Risk Management Committee Accounting and Auditing Committees Integrated Sustainability Reporting Systems King Code on constructing ethical arguments, voluntary compliance: ‘It is the legal duty of directors to act in the best interest of the company. In following ‘the apply or explain’ approach, the board of directors, in its collective decision-making, could conclude that to follow a recommendation would not, in the particular circumstances, be in the interests of the company. The board could . . . apply another practice and still achieve the overarching corporate governance principles of (1) fairness, (2) accountability, (3) responsibility and (4) transparency.’ ‘In addition to compliance with regulation, the criteria of good governance . . . will be relevant to determine what is regarded as an appropriate standard of conduct for the directors. The more established certain governance practices become, the more likely a court would regard conduct that conforms with these practices as meeting the required standard of care. . . . . Consequently, any failure to meet a recognized standard of governance, albeit not legislated, may render a board or a director liable at law.’ Do you understand how King reaches this conclusion? Standard practices and duties – accepted by the community – often become law – as determined by the courts. 7. Purposes: The purposes of Act are to promote compliance with the Bill of Rights as provided for in the Constitution . . . . 77. Liabilities of Directors and Prescribed Officers: Liability for breach of (2) fiduciary duty that result in loss, damages or cost; (3) acting name of company that as a direct or indirect consequence of director having acted in name incurred loss, damage or cost; . . . (b) acquiesced in companies’ business knowing it was prohibited. 78 Indemnification (2)... any provision of an agreement, the memorandum of incorporation or rules of a company, or a resolution of a company ... is void to the extent that it directly or indirectly purports to relieve a director of a duty contemplated in s 75 or 76; or negate, limit or restrict any legal consequences arising from an act or omission that constitutes wilful misconduct or wilful breach of trust on the part of the director. (3) A company may not ... pay any fine that may be imposed on the director of a company ...who has been convicted in terms of any national legislation. Section 7 places companies on notice that they are subject to the Bill of Rights Section 77 expands fiduciary duties of directors Section 78 attempts to pierce the corporate veil and ensure the directors place proper systems in place to monitor behaviour of company by holding them jointly and severally and directly liable – without immunization or indemnification by the company – for breaches of fiduciary duties and statutory obligations. Firms should try to meet the triple bottom line: Environmental Protection Economic Development Community Building in a manner that will enable the next generation to enjoy the fruits of this generation’s labour. The first thesis holds that the norms meant to cover the notion of corporate social responsibility (CSR I) fail to disaggregate the different companies to which the norms apply and impose on many companies duties that they cannot possibly discharge. Put differently: (a) most companies find themselves under immense pressure to satisfy domestic and international codes (as well as voluntary rules set forth by industry organization) (b) all firms, operating under the Constitution and the new Companies Act are asked to protect the environment, to ensure economic growth and to promote well-being of the communities in which companies operate, (c), the vast majority cannot – by design and even with the best intent – make good on the promise and the premise of CSR I. Few companies actually meet the high threshold set by the United Nations Global Compact, the Cadbury Report, the King III Report and the King Code on Governance Principles: all companies feel obliged to talk the talk. Again, few companies that talk the talk, walk the walk. For analytical purposes, I have divided the companies into three different categories: two categories in which firms primarily talk the talk, and one category in which firms actually walk the walk. In the first and largest category, we find the Greenwashers. Such companies commit themselves to following various codes and consign company funds to ventures that may or may not diminish carbon footprints, create new jobs or make the lives of some community members discernibly better. The efforts of such entities do not form a part of core corporate strategy. Motivations for greenwashing range from advertising, to reduced government regulation, to enhanced community relations to esprit de corp within the firm. Most importantly, Greenwashers view CSR I as an operating cost and not a source of sustainable profit. Greenbranders view CSR somewhat differently. CSR is more than a cost of doing business. From the purveyors of recycled paper to organic free chickens to ice cream, to couture fashion to banks that give users an option not to print a paper receipt, greenbranders believe that their businesses address environmental, economic and communal concerns. They consciously attempt to diminish carbon footprints, create new jobs and making the lives of some community members discernibly better. While these efforts form a part of the core corporate strategy, the scale of triple line profits remains rather small. The primary benefit of greenbranding often lies with the consumer or end user of the product or service. They view its purchase as a means toward contributing to a better world. The firm’s primary motivation for greenbranding is advertising (with a modicum of community service). For Greenbranders, CSR compliance constitutes an operating cost – but an operating cost that serves the bottom line. To the extent that CSR efforts form a successful part of a greenbrander’s marketing campaign, they are a source of sustainable profit. Greengrowers, on the other hand, see CSR as part of their core business. For Greengrowers, profit is to be had by making good on the often conflicting demands of sustainable development (environmental protection, economic development and positive community relations). Greengrowers generate new technologies or new business models that enable them to produce products and services that consumers want in a manner consistent with CSR best practices. A global manufacturer of lead batteries may, as we shall see, create a market for lead recycled from discarded batteries. If most firms do not have the vision or the skills to change existing successful business models, the ability to create new technologies, or sufficient net free cash flow to absorb the incremental costs of complying with the mandates of CSR, then what are we to make of the ‘noise’ or the ‘hallabulloo’ about CSR? The second thesis is that Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR I) should give way to a somewhat chastened, but more useful, form of Company Stakeholder Responsibility (or what I ultimately call NCSR II). NCSR II does not mean that we cannot expect some companies to fulfil the mandate of CSR I. Rather companies should do what they are able to do in the service of all their stakeholders: from stockholders, to employees, to communities and to the broader environment (political, social and natural.) Companies should be ‘nudged’ toward serving the best interest of all concerned within their capacity to make such meaningful contributions. So. One virtue of CSR II is that it removes the sometimes rank hypocrisy associated with CSR I. A second virtue is that it frees companies to think creatively about how they might better serve their stakeholders and removes the need to slavishly follow codes – or be seen to follow codes – to which the company is simply not committed. The final virtue is that it restores a belief in the common good and collective action. State intervention need not be a bureaucratic poke in the eye to business. Regulations – from tax incentives to greenfields – can actually stimulate the creation of new technologies and business strategies that serve communities here and abroad. Moreover, we should not leave ‘nudges’ to the state alone. If my analysis of the current malaise in capitalist democracies is correct, then we should not be caught hoping against hope that the state will be the only engine for the kind of change that is necessary for NSCR II to work and the triple bottom line to be met. ‘Nudges’ can come from various sources: (1) the state; (2) firms with a self-interest in their own survival over time; (3) industries and industry partners that recognize a competitive advantage in sharing technology in order to survive; (4) non-governmental organizations that tap a variety of sources for support and conduct independent research that serves the common good; and (5) the consumer, who also self-enlightened, but with an interest in the well-being of the next generation (their children) seeks solutions in the form of products that both enhance the planet’s sustainability and secure the standard of living to which they and their children have become accustomed. Most business enterprises assume that a market exists for their goods. However, built in to that surface assumption are several additional assumptions: that the poorest of the poor are not part of the target market; that the poor cannot be reached; that the poor have insufficient resources to make any return on investment too insignificant to warrant the risk. As it turns out these assumptions are largely incorrect. The bottom of the pyramid was worth over 6 trillion dollars (in 2002) – and is worth substantially more after a decade of massive growth in India and China. With a third of the world’s wealth, the bottom appears to be market sector worth pursuing. In purchasing power parity (PPP) terms, the nine major developing countries, including China, Brazil, South Africa, India and Mexico, constitute 90% of the developing world’s population, with a GDP in PPP terms larger than the combined GDP of Japan, Germany, France, Italy and the United Kingdom in PPP terms. Poorer households will spend their money on items that seem like luxury goods. In Prahalad’s view, his new paradigm shift begins with a simple proposition: if we start thinking of the poor as ‘resilient and creative entrepreneurs and value-conscious consumers, a whole new world of opportunity will open up’. His view has led many of the top 200 multinationals to rethink the orthodox view of doing business with the poor, or in emerging markets. The UNDP has distanced itself from Prahalad’s language and taken up the language of ‘Growing Inclusive Markets’. How much the current initiative and report owe intellectually to Prahalad is a matter of debate. What is clear is that UNDP is using the vast UN family of 23 international agencies and UN staff in 185 countries, 38 to create bridges between the international financial institutions, the private sector and entrepreneurs in developing countries. The UN seems to advocate public-private partnerships that are not solely reliant on market forces. Moreover, these initiatives are designed to provide ‘public goods’ that large firms are not interested in producing. The impediments that BOP consumers have to securing access to various goods sometimes appear insuperable, and certainly may be large enough to scare off multinationals who do not wish to invest significant sums in infrastructure in order to break through BOP bottlenecks. As one critic rightly notes: ‘Companies cannot simply apply top-of-the-pyramid marketing and distribution strategies, but rather must [invent] completely new tactics to reach the BOP’. Environmental Economic Protection Development Community Participation The Constitution, s 24, guarantees everyone— (a) to an environment that is not harmful to their health or well-being; and (b) to have the environment protected, for the benefit of present and future generations, through reasonable legislative and other measures that— (i) prevent pollution and ecological degradation; (ii) promote conservation; and (iii) secure ecologically sustainable development and use of natural resources while promoting justifiable economic and social development. In a judgment concurred in by all of the justices of the Constitutional Court, save Sachs J, Ngcobo J held that the Constitution recognises the interrelationship between the protection of the environment and socioeconomic development. It contemplates the integration of environmental protection and socioeconomic development and envisages that the two will be balanced through the ideal of sustainable development. He held that sustainable development provides a framework for reconciling socio-economic development and environmental protection and thus acts as a mediating principle in reconciling environmental and developmental considerations. According to Loretta Feris : ‘Sustainable development has three pillars: ‘(1) sustainable utilisation of natural resources, (2) the pursuit of equity in the use and allocation of natural resources, and (3) the integration of environmental protection and economic development. These elements attempt to give concrete existence to a concept that may be viewed as elusive and impractical, largely because the concept involves competing considerations or normative tensions.’ According to Dire Tladi, ‘The problem with the Court’s analysis, in my view, begins when the Court, in connection with section 24 of the Constitution, makes reference to the ‘explicit recognition of the obligation to promote justifiable “economic and social development”’ and links this notion with the ‘well-being of human beings’ and ‘socio-economic rights’. Precisely what that link is, the Court never explains or explores.’ ‘But the result of this linkage is that, throughout the judgement, the terms‘ socio-economic rights’, ‘development’ and ‘economic development’ are used interchangeably as the values that most often oppose the right to a clean and a healthy environment. At one point the Court, for example, refers to the integration of environmental protection and economic development. Elsewhere, the Court states that as a result of sustainable development ‘environmental considerations will now increasingly be a feature of economic and development policy’. Further on, the Court states that ‘economic development, social development and the protection of the environment’ are considered to be the three pillars of sustainable development. Finally, the Court asserts that sustainable development ‘provides a framework for reconciling socio-economic development and environmental protection’. The result of treating these concepts as interchangeable is that the Court never stops to ask whether the factors that the Fuel Retailers Association requested that the environmental authorities consider are socio-economic or purely economic. To use language from the common definition of sustainable development, the Court does not ask whether these factors are social or economic. The Court’s judgment implies — incorrectly — that economic considerations are the same as social considerations.’ By blurring the distinction between social and economic concerns, our jurisprudence flirts with the undesirable outcome of preserving the status quo: namely, paying lip service to sustainable development and integration. The failure to distinguish more carefully between these values facilitates the instrumentalisation of sustainable development for economic ends. Corporations have a responsibility to behave ethically, fairly, accountably, responsibly and transparently for stakeholders and the broader community. (King) Corporations have an obligation to stay within the law. (Friedman) Corporations have a responsibility to abide by internationally accepted norms. (UNGC) Corporations have an obligation to discharge their negative and positive duties under the Bill of Rights (Constitution). Corporations and their directors must take personal responsibility – and potentially accept liability – for their conduct. (Companies Act) Companies should strive to meet the triple bottom line. (King, UNGC, Constitution, Companies Act)