The following statement was signed by more than 100 National high

advertisement

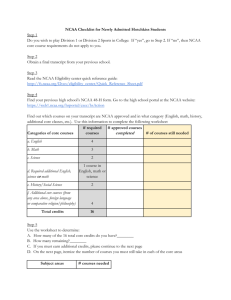

Statement on NCAA Challenge The following statement was signed by more than 100 National high school reform leaders, challenging the NCAA. An article about this statement appeared in the USA Today. The intentions of the NCAA's initial eligibility process are worthy. The approach is wrong and should be reformed immediately. When a small group of college presidents met in the early 1980's to review academic requirements for student athletes, their intent was to preserve the integrity of intercollegiate athletes. Faced with widely publicized reports about athletes who left college unable to read, the college presidents could have created rules that would have held the NCAA's own member institutions accountable for the education they provided to student athletes. Instead the presidents inappropriately chose to impose strict new requirements on high school athletes. The NCAA's Initial Eligibility Process has discouraged and dismayed thousands of students, including some of the nation's most academically able and responsible young people. The NCAA and its Clearinghouse have disrupted nationally recognized efforts to improve high schools. The NCAA bears responsibility for mistakes made by the Initial Eligibility Clearinghouse it created and funds, just as General Motors has responsibility for its sub-contractors. Remarkably, NCAA attorneys have argued that the organization does not have to follow the Americans with Disabilities Act. The NCAA is inappropriately attempting to dictate curriculum for the nation's high schools. In this country, state and local boards of education, not the NCAA, establish graduation requirements and course curriculum. The K-12 community welcomes collaboration with higher education. Dictates, especially from those with no legal authority over K-12 education, are not welcome. Current NCAA recommendations appear, for example, to reject vocational courses and independent study as appropriate for college preparation. School districts face legal liability from parents furious with the damage NCAA processes have caused, which districts had no role in creating. The NCAA should re-examine and reject current proposals for revisions in the Initial Eligibility process which attempt to dictate course content to high schools. We offer a few examples of the damage the NCAA has done. Then, we suggest several steps which should be taken immediately. Here are a few examples of the NCAA's actions. The NCAA prevented a student who with a 3.97 high school grade point average, high test scores and membership in the National Honor Society from playing football at the Air Force Academy last year. Why? The NCAA rejected l/3 of a required 10th grade English class. The New York Times, 10/ 23/96 The NCAA ruled a student with a strong academic record ineligible to accept a track scholarship on the basis of a single science class. As a result, she had to drop out of college. USA Today, 10/29/96 The NCAA tried, simply on the basis of courses taken, to prevent a high school class valedictorian from participating in college sports. This student had been appointed to one of the nation's military academies. Detroit News 12/15/96 The NCAA denied full eligibility for two student athletes in the top 10% of their Philadelphia high school while taking college preparatory courses, solely because of their standardized test scores, a violation of guidelines for test use developed by the test-makers themselves. Last January, the two students filed a class action race discrimination lawsuit against the NCAA. Cureton v. NCAA The NCAA tried to block a student from participating in basketball, rejecting his principal's contention that he had taken an acceptable number of mathematics courses. A Connecticut district court rejected NCAA arguments, noting that the NCAA's Clearinghouse Director revealed that to his knowledge, none of the people on his staff "is, or ever was a school principal or a teacher who had experience in designing courses." Phillip v. NCAA, 1996 WL 870680 (D. Conn.) Minority and lower-income student athletes are denied full eligibility at rates three to four times the rates of other students, due both to test score and course requirements. NCAA leaders ignored warnings from NCAA researchers about the disparate impact. (Washington Post 9/9/97) The NCAA rejected an innovative public school's method of evaluating students, which requires them to demonstrate skills and knowledge before graduating from high school. After a year of correspondence the NCAA informed the school that its performance based, rather than credit-based system, was inconsistent with NCAA standards. The young woman directly involved in this struggle achieved an ACT score which put her in the top 5% of students. She earned more than 80 college credits while still in high school, compiling an A- average. Yet the NCAA insisted that her college or university would have to appeal on her behalf before it would approve her athletic scholarship. St. Paul Pioneer Press, 5/27/97 A suburban teacher who the National Council of Social Studies named "outstanding teacher of the year" has spent frustrating months trying to gain NCAA approval of carefully developed interdisciplinary courses. His principal wrote the NCAA, "After having had too many experiences calling, submitting curricula, resubmitting curricula, and receiving different answers to the same questions because one can never talk with the same Clearinghouse representative, it makes my guidance counselors and me wonder whether the NCAA Academic Requirements Committee know anything at all about curricula and those components of a planned course which qualify it as a core course." Principal , Chartiers Valley High School to NCAA Academic Requirements Committee 9/11/97 The NCAA has argued in court that it does not have to comply with the Americans with Disabilities Act. The US Department of Justice disagrees. The DOJ has found that current NCAA rules specifying course and standardized test requirements for student-athletes with learning disabilities violate the federal Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). The Department of Justice has told the NCAA it should compensate a number of these student-athletes and modify their eligibility status. The NCAA now faces lawsuits from students with learning disabilities, including a swimmer now at Michigan State who was denied full eligibility because of special education courses he took early in his high school years. By the time he was a senior in high school, he was doing well in honors courses at a highly regarded suburban high school. But because of the special education courses he took earlier in his high school years, he was not allowed to compete as a college in his a freshman year. The NCAA rejected an interdisciplinary course stressing research and writing skills, thus temporarily blocking several outstanding student/athletes from participating in college sports. The NCAA's three sentence memo rejecting the course had three grammatical mistakes. (New York Times, 10/ 26/96) It is attached to this statement. The National Association of State Boards of Education recently noted, the NCAA "is interfering with states' academic reforms....the NCAA is far behind the curve of education reform efforts...the NCAA relies on the traditional and increasingly outmoded Carnegie unit - seat time, when many states and thousands of school districts are moving to assess student achievement through outcomes...and are experimenting with other innovations such as block scheduling and charter schools which are far beyond the static and limited purview of the NCAA." Fundamentally, the NCAA has assumed for itself the authority to pass judgment on high school curricula at the nation's more than 20,000 high schools, and to use SAT and ACT scores in ways not supported by people who created the tests. The NCAA has neither the right nor the capacity to act as a national school board. Current problems with NCAA's Initial Eligibility Clearinghouse are an inevitable consequence of the NCAA's massive and misguided undertaking. The NCAA can and should play a useful and constructive role in the academic lives of student athletes. However, that will require rethinking its actions, and focusing more attention on the academic work of students while they are in colleges and universities. We recommend the following: 1. The NCAA should abandon its efforts to dictate course content for American high schools. By the school year 1999-2000, the NCAA should halt its inappropriate reliance on the SAT and ACT tests. Instead, the NCAA should work with national testing and measurement authorities, some of whom are at member universities, to rethink ways to assess skills and knowledge students have when they enter college. 2. The NCAA should increase scrutiny of its own members by tightening academic requirements for student athletes who already are on college campuses, imposing stricter"continuing progress rules, and punishing colleges and universities that fail to educate their athletes. The NCAA should reconsider the issue of freshman eligibility. 3. A major national independent commission should be created, with open public meetings. Half the members should represent higher education, and half should be appointed by, and represent those legally responsible for setting K-12 curriculum standards at the state and local levels. Over the next nine months, the Commission should o invite students, parents and educators who have experience with the Initial Eligibility process to present their experiences at the Commission and at the 1999 annual NCAA meeting. The Commission should hold at least 5 open public hearings around the nation, allowing a variety of people to present their experience, research and recommendations. o re-examine the way the NCAA assesses student preparation for higher education. o review the research on the limitations as well as the strengths of standardized tests o consider other, more appropriate ways to assess what high school students know o review current NCAA policy regarding academic standards athletes are expected to meet while in colleges and universities, both in terms of acceptable and unacceptable course content, and required grade point average. o develop and present recommendations throughout the nation prior to the 1999 annual NCAA convention. o consider reinstituting the policy of making freshmen ineligible to participate in major sports, at least until they have successfully completed a quarter or semester at a higher education institution. o present a report, with explanation of reactions to it, at the next annual convention of NASBE and NCAA. Other organizations representing school administrators, principals, counselors and teachers should be invited to participate. But the NCAA should remember who has the legal authority to establish curriculum standards in high schools. 4. The NCAA should also publish and make publicly available committee meeting minutes and staff memos relating to the Initial Eligibility committee for the last 3 years, including discussions about the Clearinghouse. The NCAA also should provide research about the impact of its initial eligibility process on students, including students from different backgrounds. 5. The NCAA should follow U.S. Department of Justice recommendations regarding compensation of students with disabilities who have been inappropriately treated in the Initial Eligibility process. The NCAA should consider compensation to other students whose lives and educations have been disrupted, despite otherwise acceptable work, because the NCAA rejected one or more of their courses. People Who've Signed the Statement * Mary Beth Blegen, National Teacher of the Year, 1996 Tracey Bailey, National Teacher of the Year, 1993 Thomas A. Fleming, National Teacher of the Year, 1992 Elaine Griffin, National Teacher of the Year, 1995 Bob Rodrigues, 1997 National Council of the Social Studies "Outstanding Social Studies Teacher of the Year," and Department Head, Chartiers Valley High School, Bridgeville, PA Dr. Karen Butterfield, Arizona State Teacher of the Year, 1993 Cathy Nelson, Minnesota State Teacher of the Year, 1990 Del Holland, 1988 Iowa Alternative School Teacher of the Year Jeanne Allen, President, Center for Education Reform, Washington, D.C. Dr. Howard Fuller, Distinguished Professor of Education, Founder and Director of the Institute for the Transformation of Learning, Marquette University Dr. Asa Hilliard, Professor, Georgia State University Dr. Herbert Kohl, Senior Fellow, Open Society Institute and co-winner, National Book Award, Pt. Arena, California Jonathan Kozol, educator and author Deborah Meier, Coalition of Essential Schools Vice Chair, and Principal, Mission Hills School Dr. Vito Perrone, Director of Teacher Education Programs Harvard University Graduate School of Education Charles Rooney, National Center for Fair and Open Testing Dr. Theodore Sizer, Chair, Coalition of Essential Schools and University Professor, Brown University Bobby Ann Starnes, President, Foxfire Fund, Inc., Mountain City, Ga. Anna Amato, President, EdTec, Detroit, Michigan John Ayers, Executive Director, Leadership for Quality Education, Chicago, Illinois Dr. Gloria Bonia-Santiago, Associate Professor, Rutgers University Dr. Robert Barr, Dean, College of Education, Boise State University, Boise, Idaho Dr. Michael Bonacci, Principal, Chartiers Valley High School, Bridgeville, PA. Dr. William Boyd, Professor of Education, Penn State University Karen Byars, Executive Director, Action for Children's Education, Cambridge, Massachusetts Joe Beckmann, Development Director, OEKOS Foundation, Harvard, Ma. Steve Camron, Legal Counsel, Lenawee Intermediate School District, Adrian, Michigan Dr. James G. Cibulka, Chair, Department of Education Policy, Planning, and Administration, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland Rustin Clark, Superintendent of Schools, Chase-Raymond District, Chase, Kansas Judith E. Conger, Dean, Community High School, Ann Arbor, Michigan Frank Dooling, Tacoma, Washington J. Terry Downen, Principal, North High School, Eau Claire, Wisconsin Dr. Judy DuShane, Branch Intermediate School District, Coldwater, Michigan John Esty, Concord, Massachusetts Sy Fliegel, Senior Fellow, Manhattan Institute, New York City Greg Firn, principal, Principal, Cascade High School, Everett, Washington Laura Friedman, Director, Charter Schools Resource Center, St. Louis, Missouri Dr. Pamela George, School of Education, North Carolina Central University, Durham, North Carolina James N. Goenner, Executive Director, Michigan Association of Public School Academies, Lansing Michigan Samuel Halperin, Co-Director, American Youth Policy Forum, Washington, D.C. Mary Hartsfield, Program and Education Director, Devereux Center, Mims, Florida Frank Heller, , President, Global Village Learning, Brunswick, Maine Dr. Wayne Jennings, President, Designs for Learning, St. Paul, Minnesota Mary Johns, Vice President of the Adams Twelve School Board, Northglenn, Colorado Richard Kazis, Jobs for the Future, Cambridge, Massachusetts Dr. Jim Kielsmeier, President, National Youth Leadership Council Ron Kowalewski, Principal, Waterford Kettering High School, Waterford. MI Deborah Lazarus, ESOL Teacher, Fallsberg, New York Ed Lyell, Senior Fellow, Center for the American West, Denver, Colorado Jenny McCampbell, Consultant for Gifted/Talented, Clinton County Regional Service Agency, St. Johns, Michigan Jack Marlotte, Ann Arbor, Michigan Paul Nachtigal and Toni Haas, co-directors, Annenberg Rural Challenge Dr. Joe Nathan, Director, Center for School Change, University of Minnesota Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs Lucy Nesbeda, Director, Oekos Foundation, Harvard, Massachusetts Emanuel Pariser, Community School Co-director, Camden, Maine Dr. Frank Pignatelli, Chair, Educational Leadership Department, Bank Street College, New York Eric Premack, Director, Charter Schools Project, California State University, Sacramento Bill Quinn, North Central Regional Laboratory, Illinois Dr. Al Ramirez, Associate Professor, Educational Leadership, University of Colorado, Colorado Springs and former Chief State School Officer, Iowa Editorial Board, Rethinking Schools Magazine, Milwaukee Pamela Riley, Director Center for Innovation in Education, Pacific Research Institute for Public Policy, San Francisco Dr. Walter Roberts, Mankato State University and Government Relations Chair, Minnesota School Counselors Association Dr. Jack Shelton, Director, Program for Rural Success and Research, University of Alabama Marty Strange, Director, Annenburg Rural Challenge Policy Program Dr. Margaret Tannenbaum, Professor of Education, Rowan University, Glassboro, New Jersey 08028 Sarah Tantillo, New Jersey Charter School Resource Center Dr. Jon Thompson, Director, Oakland Science, Mathematics and Technology Academy, Clarkston, Michigan * Titles provided for information only.