Chapter 30 Pg.696-701 The War to End Wars

advertisement

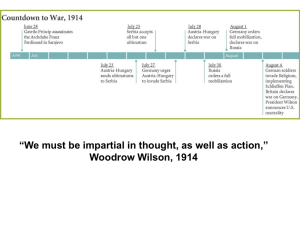

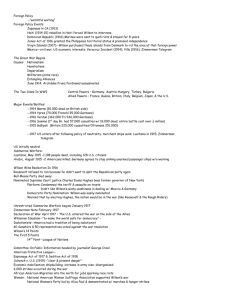

Chapter 30 Pg.696-701 The War to End Wars War by Act of Germany • On January 22, 1917, Woodrow Wilson made one final attempt to avert war, delivering a moving address that correctly declared only a “peace without victory” (beating Germany without embarrassing them) would be lasting. – Germany responded by shocking the world, announcing that it would break the Sussex pledge and return to unrestricted submarine warfare, which meant that its U-boats would now be firing on armed and unarmed ships in the war zone. • Wilson asked Congress for the authority to arm merchant ships, but a band of Midwestern senators tried to block this measure. Then, a devious telegram was intercepted by the British and published on March 1, 1917. – Written by German foreign secretary Arthur Zimmerman, the so-called “Zimmerman Note” proposed a secret agreement between Germany and Mexico. It proposed that if Mexico joined Germany in a war against the U.S., then Mexico could recover Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona from the U.S. – much of the land taken from it after the Mexican War (1846-48)! Also, the Germans began to make good on their threats, sinking numerous American ships. Meanwhile, in Russia, a revolution toppled the tsarist regime. On April 2, 1917, President Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany after German U-boats sank four unarmed American merchant vessels. Four days later Congress obliged, and Wilson had lost his gamble of staying out of the war…. The Zimmerman Note Wilsonian Idealism Enthroned Many people still didn’t want to enter into war, for America had prided itself on isolationism for decades, and now, Wilson was entangling America in a distant war. – Six senators and 50 representatives, including the first Congresswoman, Jeanette Rankin, voted against war. Thus, in an attempt to thwart such opposition, Wilson persuaded the American people to enter World War I by coming up with the righteous and patriotic idea of America entering the war to “make the world safe for democracy” and pledging that this would be “a war to end all wars.” – This idealistic motto worked brilliantly, but with the new American zeal came the loss of Wilson’s earlier motto, “peace without victory.” Wilson’s Fourteen Potent Points • On January 8, 1917, Wilson delivered his Fourteen Points Address to Congress. • The Fourteen Points were a set of idealistic goals for peace. The main points were… – – – – – An abolition of secret treaties. Freedom of the seas was to be maintained. Reduction of armaments. “Self-determination,” or independence for oppressed minority groups who’d choose their own government A League of Nations, an international organization that would keep the peace and settle world disputes. Creel Manipulates Minds The Committee on Public Information, headed by George Creel, was created to “sell” the war to those people who were against it or to simply gain support for the war. – The Creel organization sent out an army of 75,000 men to deliver speeches in favor of the war, saturated the public with patriotic tunes (most notably “Over There” – probably the most famous American war song ever), showered millions of pamphlets containing the most potent “Wilsonisms” upon the world, splashed posters and billboards that had emotional appeals, and showed anti-German movies like The Kaiser and The Beast of Berlin. Yet, the major problem for Creel and his Committee on Public Information was that he oversold Wilson’s ideals and led the world to expect too much – in effect, to believe that war WOULD forever be banished from the earth (yeah, right). Sadly, after the war was over, the result would be disastrous disillusionment by the American people (as we’ll examine when we get to the post-war era). http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/ab/'De stroy_this_mad_brute'_WWI_propaganda_poster_(US_version ).jpg Enforcing Loyalty and Stifling Dissent • During WWI, civil liberties in America were frankly denied to many, especially those suspected of disloyalty. • German-Americans were extremely loyal to the U.S., but nevertheless, many Germans were blamed for espionage activities, and a few were tarred, feathered, and beaten. • The Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918 showed American fears and paranoia about Germans, as well as others perceived as a threat. – – Antiwar Socialists and the members of the radical union Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) were often prosecuted, including Socialist Eugene V. Debs and IWW leader William D. Haywood, who were arrested, convicted, and sent to prison. Fortunately, after the war, there were presidential pardons (from Warren G. Harding), but a few people still sat in jail into the 1930s. The Nation’s Factories Go to War America was very unprepared for war, though Wilson had already created the Council of National Defense to study problems with mobilization and had launched a shipbuilding program. Evidence of our isolationist (ie. “head in the sand”, DuhNile is NOT a river in Egypt) mentality can be seen in the fact that America’s army was only the 15th largest in the world at that time, regardless of our position as the #1 industrial power on the planet. In trying to mobilize for war, no one really knew how much America could produce, and traditional laissezfaire economics (where the government stays out of the economy) still provided resistance to government control of the economy. SO…… In March 1918, Wilson named Bernard Baruch to head the War Industries Board to get big business on board for the war effort (it was disbanded soon after the armistice). Fortunately, the industrial giants “patriotically” rose to the occasion anyway without much resistance (as they realized the potentially huge profits that could be made through the production and selling of war materials) and swiftly produced incredible amounts of supplies for the war effort. Indeed, a sleeping giant had awakened…………