Emma Hickman

advertisement

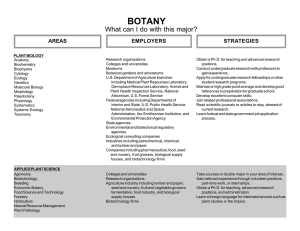

Emma Hickman Encounters with Nature 10/31/11 Drayton Abstract Drayton, Richard. “Plants and Power, and Notes.” In Nature’s Government, Science, Imperial Britain, and the ‘Improvement’ of the World, 26-49, 281-286. New York: Yale University Press, 2000. In chapter two of In Nature’s Government, Science, Imperial Britain, and the ‘Improvement’ of the World, Drayton explores the questions, What is the connection between botany and power in England from 1550 to the mid-eighteenth century and what prompted the rise in popularity of botanical patronage? He begins this analysis through discussing the evolution of botany in England. At first, the gardens of Europe were intended merely for offering pleasure to the senses and essentially they were valued purely aesthetically. As time progressed however, ornate botanical gardens came to be associated with status and wealth. Finally, as influential thinkers began to draw connections between nature and power, gardens came to symbolize the providential right to rule. Rulers who were familiar with the laws that governed nature were expected to be much more knowledgeable in the governmental structure that he or she was a part of. The rise of popularity in botanical patronage was mainly a result of this belief, that rulers or people of power could elevate their image by providing for the civic good through support of botanical exploration. In addition, Linnaeus’ new classification system made science, botany in particular, more accessible to those who weren’t as learned as the scientists of the day. Gardens came to be used in many different ways, mainly to illustrate the virtue of the leader who was patronizing them but also as political tools to either improve diplomacy or make a political statement. In his analysis Drayton uses several primary source documents to provide examples of the points he makes. He relies mainly on excerpts from book dedications and scientific literature of the time period. This subject was truly fascinating to me. It came as a definite surprise that botany played such a large role in increasing the legitimacy of power of European rulers. Drayton wrote an excellent analysis with insightful comments and well researched points. Knowledge of natural ways is a powerful tool, one that can assist in predicting the dynamics of one’s people. In this way, knowledge of nature can be seen as vital to a ruler. Walpole Abstract “The History of the Modern Taste in Gardening.” In the Genius of the Place, edited by John Dixon Hunt and Peter Willis, 313-316. New York: Harper & Row, publishers, 1975. In his 1975 work, “History of the Modern Taste in Gardening”, Walpole argues the merits of the trend of merging the natural and beautiful rugged landscape with the proper and orderly garden of the English countryside. He particularly commends the artist, Kent, for being able to capture with such talent the attraction of this innovative interweaving. Kent was able to paint these landscapes but with additions or embellishments as he saw fit. However, at the same time, Walpole criticizes Kent for taking the depiction of rugged nature too far in his planting and painting of dead trees. Walpole concludes with the idea that at times, a neat English garden is sometimes better than the attempt to constantly incorporate the romantic wilderness into a landscape. I was drawn in by the piece however some of Walpole’s ideas were scattered and difficult to understand. The significance of this piece is in the description of the developing trends of gardening and how they evolved. Emma Hickman Encounters with Nature 10/31/11 Thomas Abstract Thomas, Keith. “Cultivation or Wilderness?” In Man and the Natural World: Changing Attitudes in England, 1500-1800, 254-269. New York: Oxford University Press, 1983. In Keith Thomas’s “Cultivation or Wilderness?”, Thomas provides an analysis of the changing perceptions of nature throughout the 17th and 18th centuries. At the beginning of the 17th century, many people were of the belief that all natural land should be cultivated and put to some use mainly agriculturally. This belief was firmly held and many thought that uncultivated land was an enormous waste of resources, which was believed by some to be an affront to God. However in the late 18th century, this view began to change. People appreciated the land more and more; they began to create landscape gardens that were often not very different in appearance from uncultivated fields. This change stemmed from, among other things, a great theological debate at the time, that the world had in fact not degenerated since it’s Creation, and that natural landscapes were quite breathtakingly beautiful and inspirational. This argument pervaded society and created a mad passion for wild landscapes and especially rugged mountains. This new belief also stemmed from the new easy availability of transportation to isolated wilderness and intellectual trends that were being developed in the literature of the time period. Thomas’s discussion was very insightful and the topic drew me in very much. This analysis is important because it shows how easily the popular opinion can change with regard to nature simply according to the trends at the time.