Words - Columbia University

advertisement

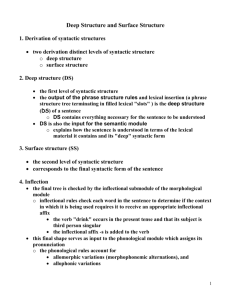

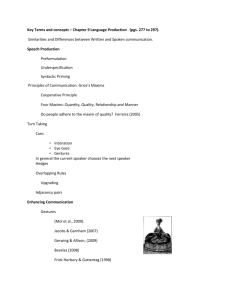

Language and Cognition Colombo, June 2011 Day 4 Psycholinguistics Experimental approaches to understanding language Studying speech errors • The systems involved in speech and language production usually work seamlessly • But when the system breaks down, that can tell us something about how it was working in the first place – Speech can go wrong in many ways – Different components of speech can “slip” – The errors are not random • Look for regularities in the patterns of errors “Spoonerisms” • Reverend Dr. William Archibald Spooner, 1844-1930. – Lecturer, tutor, and dean at Oxford university famous for speech errors – Some famous examples: Nosey little cook FOR ... Cattle ships and bruisers Cosy little nook FOR ... Battle ships and cruisers ..we’ll have the hags flung out FOR ... ..we’ll have the flags hung out you’ve tasted two worms” kisstomary to cuss the bride. FOR ... .. you’ve wasted two terms FOR ... customary to kiss the bride Speech errors: Shift • One segment disappears from its appropriate location and appears somewhere else • The thing that shifts moves from one element to another of the same type ..in case she decide to hits it. “a maniac for weekends.” FOR FOR ...in case she decides to hit it “a weekend for maniacs.” Speech errors: exchange • Like a “double shift” – two linguistic units change places – You have hissed all my mystery lectures (target: You have missed all my history lectures) – You had your model renosed (target: you had your nose remodelled) What can we learn from shift errors? “a maniac for weekends.” FOR “a weekend for maniacs.” • Notice that /s/ is pronounced /z/ in the context +voice___ • So from this error we can infer that – Speech is planned in advance. – Accommodation to the phonological environment takes place (plural pronounced /z/ instead of /s/). – Order of processing is – Selection of morpheme error application of phonological rule Phonemic speech errors • Anticipation: replacing an earlier segment with a later segment – It’s a meal mystery (target: it’s a real mystery) – Bake my bike (target: take my bike) • Perseverance: an earlier segment replaces a later one (while also being articulated in its correct location) – Give the goy (target: give the boy) – He pulled a pantrum (target: he pulled a tantrum) What can we learn from phonemic errors? • Consonant-vowel rule: consonants never exchange for vowels or vice versa – Suggests that vowels and consonants are separate units in the planning of the phonological form of an utterance • Errors produce legal non-words (or unintended real words) – Suggests that we use phonological rules in production • Lexical bias effect: spontaneous (and experimentally induced) speech errors are more likely to result in real words than nonwords • Grammaticality effect: when words are substituted or exchanged they typically substitute for a word of the same grammatical class Sub-phonemic speech errors • bat a tog (target: pat a dog) • Is this a double substitution (/b/ for /p/ and /t/ for /d/)? – /p/ and /t/ are vocieless plosives and /b/ and /d/ voiced plosives – Better analysed as a shift of the phonetic feature voicing • From this we can infer that – phonetic features are psychologically real - must be units in speech production Word-level speech errors: Blends • occur when more than one word is being considered, and the two blend into a single item • Didn’t bother me in the sleast (least + slightest?) • I didn’t explain it clarefully enough (clearly + carefully?) Word level speech errors: malapropisms • when one segment is replaced by an intruder • differs from the other types of errors since the intruder may not occur at all in the intended sentence – “Jack” is the president of the sentence (target: “Jack” is the subject of the sentence) – I am stuttering psycholinguistics (target: I am studying psycholinguistics) What can we infer from word-level speech errors? • That speech is planned in advance – blends indicate speaker has activated representations of more than one word per concept • Substitutions indicate that the lexicon is organised phonologically and semantically – Substitutions appear to occur after syntactic organisation as substitutions are always from the same grammatical class (noun for noun, verb for verb etc.) • External influences - situation and personality also influence speech production • Implications for theories of language production Problems with speech errors • Not an on-line technique – depends on observation, reporting, anecdote • We only remember (or notice) certain types of errors • People often don’t (notice or) write down errors which are corrected part way through the word, e.g. “wri..wrong one” • Can’t be replicated • Even very carefully verified corpora of speech errors tend to list the error and then “the target”. – However, there may be several possible targets. – Saying there is one definitive target may limit conclusions about what type of error has actually occurred. • Evidence that we are not very good at perceiving speech errors (Ferber, 1991 – TV announcer errors) Experimental methods in psycholinguistics – The SLIP technique - speech error elicitation (Motley and Baars 1976) Task: Say the words silently as quickly as you can Say them aloud if you hear a ring dog bone dust ball dead bug doll bed “darn bore” barn door Experimental speech errors Some basic findings • This technique has been found to elicit 30% of predicted speech errors. • Lexical Bias effect: error frequency affected by whether the error results in real words or non-words More likely “wrong loot” FOR “long root” “rawn loof” FOR “lawn roof “ Syntactic priming • Bock (1986): syntactic persistance tested by picture naming TASK: Hear and repeat a sentence Describe the picture Syntactic priming a: The ghost sold the werewolf a flower b: The ghost sold a flower to the werewolf a: The girl gave the teacher the flowers b: The girl gave the flowers to the teacher Syntactic priming • In real life, syntactic priming seems to occur as well – Branigan, Pickering, & Cleland (2000): • Speakers tend to reuse syntactic constructions of other speakers – Potter & Lombardi (1998): • Speakers tend to reuse syntactic constructions of just read materials From thought to speech Message level Syntactic level Morphemic level Phonemic level Articulation • Propositions to be communicated Selection and organization of lexical items Morphologically complex words are constructed Sound structure of each word is built From thought to speech Message level • Propositions to be communicated Syntactic level Morphemic level Phonemic level Articulation Not a lot known about this step Typically thought to be shared with comprehension processes, semantic networks, situational models, etc. From thought to speech Message level • Grammatical class constraint Syntactic level • Slots and frames – Most substitutions, exchanges, and blends involve words of the same grammatical class – A syntactic framework is constructed, and then lexical items are inserted into the slots Morphemic level Phonemic level Articulation From thought to speech Message level Stranding errors I liked he would hope you I hoped he would like you Syntactic level Morphemic level Phonemic level Articulation – The inflection stayed in the same location, the stems moved – Inflections tend to stay in their proper place – Do not typically see errors like The beeing are buzzes The bees are buzzing From thought to speech Message level Stranding errors • Closed class items very rare in exchanges or substitutions Syntactic level Morphemic level Phonemic level Articulation – Two possibilities • Part of syntactic frame • High frequency, so lots of practice, easily selected, etc. From thought to speech Message level Syntactic level Morphemic level Phonemic level Articulation • Consonant vowel regularity – Consonants slip with other consonants, vowels with vowels, but rarely do consonants slip with vowels – The implication is that vowels and consonants represent different kinds of units in phonological planning From thought to speech Message level Syntactic level Morphemic level Phonemic level Articulation • Consonant vowel regularity • Evidence for the separation of meaning and sound Tip of the tongue Tip-of-the-tongue Uhh… It is a.. You know.. A.. Arggg. I can almost see it, it has two Syllables, I think it starts with A ….. • TOT – Meaning access – No (little) phonological access – What about syntax? Tip-of-the-tongue • “The rhythm of the lost word may be there without the sound to clothe it; or the evanescent sense of something which is the initial vowel or consonant may mock us fitfully, without growing more distinct.” (James, 1890, p. 251) Conclusions • Speech errors have provided data about the units of speech production. Phonology - consonants, vowels, and consonant clusters (/fl/) can be disordered as units. Also, phonetic features. Syllables which have morphemic status can be involved in errors. Separation of stem morphemes from affixes (inflectional and derivational). Stress? Stress errors could be examples of blends. Conclusions Speech errors have provided data about the units of speech production. – Syntax -grammatical rules may be applied to the wrong unit, but produce the correct pronunciation (e.g. plural takes the correct form /s/, /z/, or /iz/. • Indicates that these parts of words are marked as grammatical morphemes. – Phrases (e.g. NP) and clauses can be exchanged or reversed. – Words - can exchange, move, or be mis-selected. FROM THOUGHT TO SPEECH • How does a mental concept get turned into a spoken utterance? • Levelt, 1989, 4 stages of production: 1 Conceptualising: we conceptualise what we wish to communicate (“mentalese”). 2 Formulating: we formulate what we want to say into a linguistic plan. – Lexicalisation – Lemma Selection – Lexeme (or Phonological Form) Selection – Syntactic Planning 3 Articulating: we execute the plan through muscles in the vocal tract 4 Self-monitoring: we monitor our speech to assess whether it is what we intended to say, and how we intended to say it Models of language production Models of other aspects of language processing • Word production • In response to different kinds of stimuli • Written word reading, naming seen objects, repeating heard words, writing heard words, reading silently, reading aloud, writing to dictation…. • All involve different steps but access similar representations