11/2

advertisement

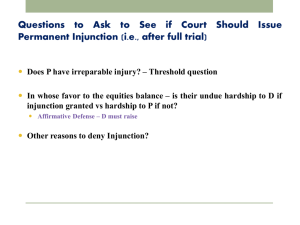

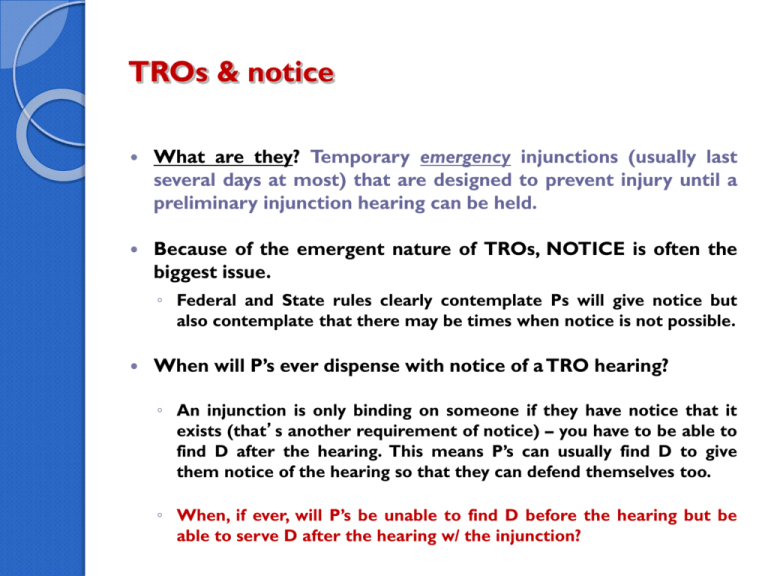

TROs & notice What are they? Temporary emergency injunctions (usually last several days at most) that are designed to prevent injury until a preliminary injunction hearing can be held. Because of the emergent nature of TROs, NOTICE is often the biggest issue. ◦ Federal and State rules clearly contemplate Ps will give notice but also contemplate that there may be times when notice is not possible. When will P’s ever dispense with notice of a TRO hearing? ◦ An injunction is only binding on someone if they have notice that it exists (that’s another requirement of notice) – you have to be able to find D after the hearing. This means P’s can usually find D to give them notice of the hearing so that they can defend themselves too. ◦ When, if ever, will P’s be unable to find D before the hearing but be able to serve D after the hearing w/ the injunction? How much notice is required for a TRO? With preliminary injunctions: ◦ Notice cannot be dispensed with – see FRCP & MRCP rules. ◦ All preliminary injunction hearings are typically dealt with as written motions on at least 10-14 days notice. These time lengths are generally governed by local rules. What type of notice is typically required of TRO requests – assuming P is not trying to dispense with notice altogether? ◦ Under FRCP? ◦ Can P wait until the last minute to give notice even if P knows where D is? In what circumstances is delayed notice okay? How does MO law deal with the length of notice issue? How long can TRO’s last? When TRO’s issue w/out notice, they are generally limited in duration by rule: ◦ FRCP 65(b)(2) – expires 14 days after entry if the court has not set an earlier expiration date Court can extend the order for a “like period” if other party consents or there is “good cause” Raises interesting question – what is the duration TROs issued with notice? ◦ Federal rules don’t speak to this issue. Sampson v. Murray Facts ◦ P moved for TRO restraining her employer from dismissing her pending pursuit of administrative appeal; DCT granted TRO ◦ DCT continued TRO indefinitely until D produced P’s supervisor as a witness in person ◦ On appeal, SCT characterized the TRO as a preliminary injunction rather than a TRO Why would SCT treat an injunction that everyone thought of as a TRO as a preliminary injunction? ◦ SCT wanted to reach the merits of the issue; can’t do that unless D can appeal & under federal law can’t appeal TROs ◦ Why is it a problem to be subject to a TRO of unlimited duration that you can’t appeal? ◦ What problems arise from treating the TRO as a preliminary injunction? More re TROS of Unlimited Duration w/ Notice Sampson – treats TRO w/ notice of unlimited duration as preliminary injunction, which allows D’s appeal of the injunction ◦ Compare Granny Goose (p. 370 n.2) – SCT found unlimited TRO w/ notice was a TRO that expired per time limits in the rule. Ds were not in contempt for ignoring TRO after those time limits. Which approach is federal court more likely to use re characterizing TROs? ◦ Courts tend to follow Sampson’s approach (especially when the hearing is more formal – i.e., longer hearing w/ D’s participation, more formal notice & evidence) but if hearing was very informal and court was unclear about extending TRO, they may use Granny Goose Both approaches are designed to give courts tools to maneuver out of an injunction that is potentially of unlimited length and unappealable0 Practical tips re unlimited TROs under FRCP: If a federal court issues a TRO of unlimited duration without notice to the defendant ◦ It will either expire by the terms of the order ◦ Or it will expire under the time limits written into the rule If a federal court issues a TRO of unlimited duration with notice to the defendant, the litigants should seek clarification: ◦ D should move the court to modify or dissolve it. ◦ If the court refuses to modify or dissolve the order, D may be able to appeal that ruling. ◦ After the time limits in the rules have run, D can violate the order (Granny Goose) or try to appeal it as a prelim. injunction (Sampson) Note Missouri’s approach avoids these problems: TRO’s with OR w/out notice are limited in duration by rule. ◦ MRCP 92.02(a)(5) & 92.02(b)(4) eBay, Inc. - The new “traditional” test for permanent injunctions & its relationship to preliminary relief ◦ Facts: Mercexchange alleged patent infringement re business method patent against eBay and won. District court refused to issue permanent injunction but Court of Appeals said injunction was warranted because of the “general rule that courts will issue permanent injunctions against patent infringement except in exceptional circumstances.” SCT reversed CTA and announced that to qualify for a permanent injunction, based on “well-established principles,” P must demonstrate: P has suffered irreparable injury P’s remedies at law are inadequate (including damages) Considering balance of hardships between P and D, an equitable remedy is warranted Public interest is not disserved by the permanent injunction This looks a lot like the test for preliminary relief (although prong 1 is different – no likelihood of success on the merits inquiry) Potential problems with the eBay approach & permanent injunctions Factors 1&2 are the same thing – aren’t they? ◦ Does court mean to require that P show “past harm” with prong 1? Factor 3 has always been a DEFENSE to permanent injunctions – now SCT acts as if P has to prove balance favors P ◦ Plus “balancing the equities” (aka undue burden on D) has traditionally meant many different things given how culpability factors in to court’s decision – courts used judgment here Courts have always considered factor 4 (public interest) as it was relevant but it was never P’s burden to show this factor favored P Lower federal courts have begun using the eBay approach in various cases (not just patent cases). ◦ Implications – fewer presumptions of irreparable harm as courts used to use (e.g., from damage to land) – P’s more likely to have to show ACTUAL harm as with preliminary injunctions ◦ State courts still take traditional approach like Whitlock v. Hilander What is a declaratory judgment? A method by which a person fearing injury from another can clarify and conclusively determine rights prior to actual injury occurring. ◦ Example: ◦ Wallace plaintiff seeks a judicial declaration that Tennessee’s excise tax on gasoline purchased elsewhere but stored in Tenn. violates the commerce clause and 14th Amdt. prior to the tax actually being assessed and/or D’s refusal to pay. Declaratory judgments are a purely statutory creation: ◦ Uniform DJA – adopted in Missouri (Mo. Rev. Stat. 527.010-080) ◦ Federal DJA – 8 USC '' 2201-02 In what types of situations does one most commonly use declaratory judgments? Constitutional challenges to statutes or regulations ◦ Does the law as applied to P (e.g., Wallace) or on its face violate state or federal constitutional provisions? Intellectual Property litigation ◦ Patent or trademark validity in the midst of an infringement dispute Insurance Coverage litigation ◦ Insured may seek determination of scope of insurance coverage while in dispute with insurer or third party Will Contests ◦ Beneficiary/potential beneficiary may seek declaration that is entitled to recover (or entitled to a certain amount) during a will contest Contract disputes (or avoidance thereof) ◦ Party to contract may seek declaration as to the parties’ rights to resolve uncertainty and avoid further dispute. Declaratory Judgments & Threshold Requirements – based on Wallace TN law requires P to pay a gasoline privilege tax (for storing w/in Tennessee gasoline that was purchased out-of-state). P claims tax violates commerce clause & 14A. To enjoin future enforcement of the TN statute in Wallace, P would have to show irreparable injury and a ripe threat of harm. Does P have to show irreparable injury to get a declaratory judgment that the statute is unconstitutional? 28 USC § 2201(a) & Mo. Rev. Stat. § 527.010 Does P have to show a threatened injury is ripe in order to get a declaratory judgment that the statute is unconstitutional? Was the threat ripe in Wallace? Ripeness laws: & potentially unconstitutional Can P simply challenge a law once its enacted (assuming P engages in activity w/in laws parameters) or must P show that the State has actually threatened to enforce the law against him? In other words, is there a ripe threat of harm merely because the statute exists and can be enforced against P? Courts answer this differently: Some say the coercive effect of the law creates a ripe threat of injury and P can sue for a declaratory judgment • • This tends to be more true if the cost of compliance is high or the risk of escalating penalties for non-compliance is significant (e.g., daily penalties for non-compliance) Others say the state must make some movement toward enforcement before an injury is ripe. • • But that movement toward enforcement can be as insignificant as a warning letter or statement to P