5-Way Stop Week 4 Transcript

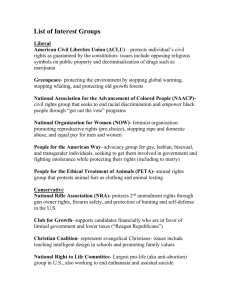

advertisement

Week 4, Stopping With Mind Transcript Hello everyone, once again. Welcome to Week 4 of The 5-Way Stop, Stopping with Mind. Of course it’s not as if you haven’t been stopping with mind all along. Body and speech are all mind, from one point of view, and we describe stopping practice altogether as a way to reconnect with our more expansive and unencumbered state of mind. So what will we look at today that we haven’t been looking at already? Well, nothing really. I don’t think there’s anything I’ll touch on today that you haven’t encountered already along the way. But we’re going to amplify two things. We’re going to AMPLIFY technique, what do you do with your mind when you stop. And in preparation for that, we’re going to amplify your understanding of the fluidity, the fickle shiftiness of your mind. We’ll look at technique last, and start with the fluid, fickle nature of your experience, which is what you apply the technique to. First of all, when you stop with mind you’re not trying to stop your mind. You’re not trying to stop thinking. If you’re alive, you think. If you stop thinking, you’re flat-lining. So please don’t try to stop thinking, it’s bad for your health. Instead, when you stop, notice what you’re thinking about. Notice what you were thinking about before you stopped. What thought made you stop? If it was a physical experience that stopped you, that’s still got a thought attached to it. A loud noise, for instance, produces the thought, “loud noise.” Then maybe “Gun shot,” or “Toddler knocking over furniture.” And that leads immediately to crane@cranestookey.com www.cranestookey.com (902) 240-5904 some further thought. “Terrorist attack,” or “My best lamp shattered,” or “Injured toddler.” No matter how engrossed you were in your previous train of thought, no matter how big and solid and all-consuming that train of thought seemed, all it takes is a loud noise for all that big solid thought to vanish, and be replaced by another big solid-seeming thought, maybe even bigger and more solid because it includes fear. And the new big, solid thing is about something that hasn’t even actually happened. There’s no terrorist attack, no broken lamp, the toddler’s fine. It doesn’t take a loud noise interrupting you either. Your train of thought derails all the time. Sometimes it’s like an endless switching yard, tracks leading off in all directions, a complexity of rail switches and intersections changing and changing and changing again, and you never know where your train of thought is heading next. Maybe a lot of people around you, it feels as if they’re manning the switches, redirecting you to suit their personal frenzy. Maybe the switches are all going on their own, totally random, and you have no idea where your train of thought thinks it’s going. Sometimes it’s the full catastrophe train wreck. Fears and angers take charge out of nowhere and next thing you know you’re train of thought is a heap of twisted metal, oil cars burning, thick, black smoke everywhere. And then a little hungry-for-lunch train comes tooting along, the train wreck vanishes, and you’re rolling through a pleasant countryside of thoughts of food. The train wreck seemed like the whole world a moment ago. Now you’re driving Thomas the Tank Engine and feeling cheery. When you stop, you have a chance to notice that the whole thing is like a child’s train set. You can pick up any car or engine and hold it in your hand. None of them are the huge, multi-ton behemoths that you thought they were. None of your trains of thought are steaming inexorably toward their immutable destiny. Even the train of thought that’s carrying the one big deadline that will make or break your career, even that train may run out of track at any moment and be replaced by Thomas the Tank Engine. This doesn’t mean that the deadline that will make or break your career is a toy train, not to be taken seriously. There are big things in your life that deserve to be given your undivided attention. But by stopping, you can recognize two things about all your trains of thought, even the life-changing ones. 2 First, while there are things that deserve to be given your undivided attention, your undivided attention is not yours to give. Other trains of thought come tooting in and out. That’s just how it is. That’s how your mind works. Second, whatever the gravity of the issues that occupy your thoughts, your thoughts about those issues, the thoughts themselves, have no gravity at all. Your thoughts have no substance. They’re not even toy trains. They’re mist. Thick and all-engulfing for a time. Then shifting, dissolving. Fickle. Your thoughts are much more fluid than the sold things you take them for. When you stop, you have a chance to notice the shifting insubstantiality of your thoughts. “What was I thinking about just now? What was I going to start thinking about next? I knew a moment ago, before I started thinking about coffee, or my grocery list, or my fight with my spouse. Where did my train of thought go?” So at this point some of you may be thinking, “Wait a minute. Stopping practice is supposed to help me think better, make my thoughts less misty, make my thinking more substantial, less fickle, more productive. Stopping practice is supposed to help me give my undivided attention to everything I do. Not help me see that my mind is really just a fog that I have no control over. That’s not helpful.” Okay, you’re right. But there’s a paradox here. The way to make your thinking into a hard-working, supportive ally instead of a distraction is to see your thinking for what it is. When you see how insubstantial your thoughts are, your thoughts lose some of the weight and momentum and thickness that propel you willy-nilly through your day. If stopping practice serves to cut through the vapour trail of preoccupation you can get lost in, as I like to say, the more you see the your thoughts as vapour, the quicker your vapour trail can dissipate. The seeming solidity of your thoughts makes them heavy, inflexible, claustrophobic, encumbering. Seeing that your thoughts are not as solid as you think, that in itself is very expansive. Very unencumbering. Your thoughts become fluid, malleable, responsive. When you recognize how your mind actually works, when you recognize the insubstantiality of your thoughts, then you can relax, and be more patient with yourself. Not only are you less likely to get caught in a misdirected or unproductive or claustrophobic train of thought, but when you notice that you have been caught in something like that, you can more easily bring yourself back to the more expansive state of mind, because you know how fickle your mind is. You don’t have to beat yourself up about it. It’s just how your mind works. Beating yourself up about it isn’t expansive. It’s very encumbering. 3 So here’s the technique. When you stop, notice your thinking. Let your attention rest on something undemanding, and notice how your previous train of thought loses its grip, loses its weight, loses its momentum. Notice that it never really had those qualities in the first place. Notice how your thoughts, in general, don’t have the grip, the weight, the momentum that you think they do. Your thoughts are much more fluid and flexible than that. This doesn’t have to be a big analysis, another thought project to get all heavy about. You can just let your attention rest on something outside the window, or on the colour of the wall, or on the feel of your feet on the floor, or on the space under the table. Without comment. Then when a commenting thought comes up in your mind, or another train of thought starts rolling, notice that. Notice it with appreciation. “Oh yes, my mind is off thinking again. That’s what it does. What a nice little thought it’s having. Or my, what a big impressive, important thought it’s having. I wonder what it will think next.” And then let your attention come back to resting on the view out the window, or the colour of the wall, or the feel of your feet on the floor, or the space under the table. When another comment or train comes up, notice again, “Oh yes, here’s another thought.” And back to the view, the wall, your feet, the space under the table. Because your mind is not going to stop thinking, the way to “stop” it is to give it something undemanding to think about. Like the colour of the wall. If you don’t feed your mind something it will starting feeding on whatever it can find. So feed it something simple, and let it relax. Feed your mind something simple, and let it unencumber itself. Feed your mind something simple so it’s not ravenously leaping about looking for something to feed on. And when your mind becomes unsatisfied with the simple stuff you’re feeding it, and starts to cook up something else, you can appreciate the quality of the cooking, so to speak, and then come back to something simple. Even within 60 seconds of stopping, there will be multiple restarts, when your mind starts cooking something up again. The practice of stopping is not about maintaining some pure, still, simple experience. That’s just not how your mind works. The practice of stopping is repeatedly noticing what your mind is doing, giving it a simple alternative, noticing what your mind does with that, giving it the simple alternative again, over and over through 60 seconds, 90 seconds, however long you try to stop. Stopping’s not in the quality, “Oh, what a great stop I’m having right now.” Stopping is in the quantity, “Ah yes, my mind is dumpster diving again.” So yu call it back. “Yoo hoo, over here!” Again, and again, and again. 4 When you become good at this, it’s easier to notice what your mind is doing moment by moment throughout the day, and repeatedly give it a simpler alternative for a moment, even just for a flash, so your mind can relax and expand. Whenever you give your mind a simple alternative for a moment, even something as simple and brief as listening to the sound of the phone ring or feeling the doorknob in your hand, you lay the ground for two helpful possibilities. One, you make your mind freshly ready for you to give it something more useful to think about, like the task at hand. Or you make your mind freshly ready to produce an unexpected insight on its own, something you’ve been needing to realize but hadn’t made the space for. It’s important, when you’re bringing your mind back to something simple and undemanding, not to be harsh about it. You’re not trying to corral your mind, pen your mind in. There’s a Zen saying that the way to control your cow is to give it a big field. When you stop, your attention is the field. By trying hard to concentrate your attention on a simple, undemanding thing, and reprimanding yourself when you can’t, you make the field small. By letting your attention rest lightly on a simple, undemanding thing, you make the field big. In that bigger field, you can let your mind think whatever it likes, so long as your mind still knows it’s in a big field. In other words, when thoughts come up, you don’t say to yourself, “No, none of that. I’m nailing you to the colour of the wall, I’m confining you in the space under the table.” And then the thought rebels and carries you with it. Instead, you can say, “Okay, a thought. Plenty of space for you here. So much space, in fact, that I don’t even need to pay attention to you. No need for me to follow you around and feed you.” And then the thought has nothing to latch on to, and it can dissipate. Leaving you in that expansive, unencumbered state of mind, your place of fresh start. Now, resting in the big field can be hard. There’s so much else to do. So much to think about. You have to play cowboy with your thoughts all the time, get this herd to the railroad line so you can get it all on your next train of thought and head out. So when you stop, you feel the urge to get going again. Right away. Fifteen seconds pass and you think, “Okay, that’s enough, I’ve got to keep moving.” This is where another aspect of the technique of stopping with mind comes in. When the urge to get going again strikes you, just sit with it for another moment. Ask yourself, why do I need to start again right now? What bad thing happens if I wait another 30 seconds. If I wait through two or three more urges to get going?” Ask yourself this, come back to the undemanding thing you rest your attention on, and do this two or three more times than you’re comfortable with. 5 Your train of thought doesn’t control the train schedule. You do. You may not control the deadline you’re trying to meet, but you control how much you rush to meet it, and how much you give yourself the freshness of mind you need to meet it deliberately. So don’t give in to the first urge to get going again. Lastly, one more thing about stopping with mind. When you stop, you have the chance to notice your thoughts. It’s just as true that your thoughts can be the things that stop you. Stop you in your tracks sometimes. An unexpected wave of fear or anger that comes over you, when last week’s fight with your spouse suddenly, unexpectedly resurfaces. A sudden burst of delight that hits you out of the blue, when something your child said pops into your mind. Just as any physical experience, like the phone ringing, can be both a reminder to stop and a technique for stopping, your mental experiences can too. Your thoughts can ring much louder than the phone. When they do, stop long enough to intentionally savour the delight, or intentionally notice and let go of the vividness of the fear, and then let your attention rest for another moment, before you get going again. Every experience, every movement of the mind, can be a reminder and a technique for stopping. This can become a very powerful mental skill, using confusion, for example, as a reminder and a path to find clarity. Using anger as a reminder and a path to find gentleness. Using speediness as a reminder and a path to find deliberate action. When we practice stopping with mind, we practice stopping with everything. So there’s nothing missing. Everything we need to stop with, we have in abundance. Everything we need to proceed with, we have in abundance. But we have to keep stepping off the speeding train into the field. Again and again. Again and again. And again. Have good stopping this week. Next week, our last, we’ll bring together all we’ve done so far, as the roadmap to finding our personal best performance, on the spot, when we need it. Until then, stop well. 6