Document

advertisement

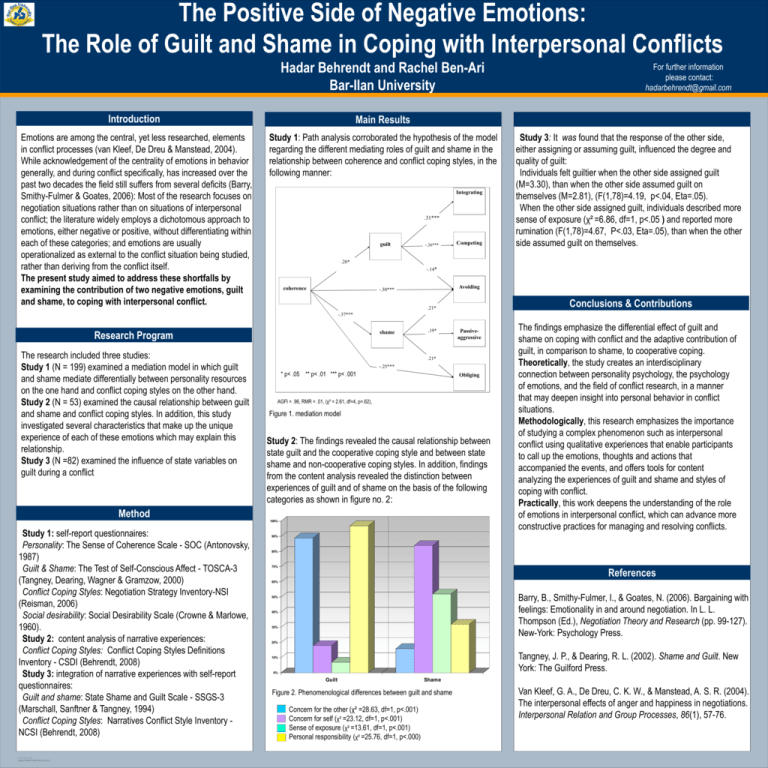

The Positive Side of Negative Emotions: The Role of Guilt and Shame in Coping with Interpersonal Conflicts Hadar Behrendt and Rachel Ben-Ari Bar-Ilan University Introduction Main Results Emotions are among the central, yet less researched, elements in conflict processes (van Kleef, De Dreu & Manstead, 2004). While acknowledgement of the centrality of emotions in behavior generally, and during conflict specifically, has increased over the past two decades the field still suffers from several deficits (Barry, Smithy-Fulmer & Goates, 2006): Most of the research focuses on negotiation situations rather than on situations of interpersonal conflict; the literature widely employs a dichotomous approach to emotions, either negative or positive, without differentiating within each of these categories; and emotions are usually operationalized as external to the conflict situation being studied, rather than deriving from the conflict itself. The present study aimed to address these shortfalls by examining the contribution of two negative emotions, guilt and shame, to coping with interpersonal conflict. Study 1: Path analysis corroborated the hypothesis of the model regarding the different mediating roles of guilt and shame in the relationship between coherence and conflict coping styles, in the following manner: Integrating .31*** guilt -.26*** Competing For further information please contact: hadarbehrendt@gmail.com Study 3: It was found that the response of the other side, either assigning or assuming guilt, influenced the degree and quality of guilt: Individuals felt guiltier when the other side assigned guilt (M=3.30), than when the other side assumed guilt on themselves (M=2.81), (F(1,78)=4.19, p<.04, Eta=.05). When the other side assigned guilt, individuals described more sense of exposure (χ² =6.86, df=1, p<.05 ) and reported more rumination (F(1,78)=4.67, P<.03, Eta=.05), than when the other side assumed guilt on themselves. .20* -.14* coherence Avoiding -.30*** Conclusions & Contributions .21* -.37*** Research Program The research included three studies: Study 1 (N = 199) examined a mediation model in which guilt and shame mediate differentially between personality resources on the one hand and conflict coping styles on the other hand. Study 2 (N = 53) examined the causal relationship between guilt and shame and conflict coping styles. In addition, this study investigated several characteristics that make up the unique experience of each of these emotions which may explain this relationship. Study 3 (N =82) examined the influence of state variables on guilt during a conflict shame .19* .21* -.25*** * p< .05 ** p< .01 *** p< .001 Obliging AGFI = .96, RMR = .01, (χ² = 2.61, df=4, p=.62), Figure 1. mediation model Study 2: The findings revealed the causal relationship between state guilt and the cooperative coping style and between state shame and non-cooperative coping styles. In addition, findings from the content analysis revealed the distinction between experiences of guilt and of shame on the basis of the following categories as shown in figure no. 2: Method 100% Study 1: self-report questionnaires: Personality: The Sense of Coherence Scale - SOC (Antonovsky, 1987) Guilt & Shame: The Test of Self-Conscious Affect - TOSCA-3 (Tangney, Dearing, Wagner & Gramzow, 2000) Conflict Coping Styles: Negotiation Strategy Inventory-NSI (Reisman, 2006) Social desirability: Social Desirability Scale (Crowne & Marlowe, 1960). Study 2: content analysis of narrative experiences: Conflict Coping Styles: Conflict Coping Styles Definitions Inventory - CSDI (Behrendt, 2008) Study 3: integration of narrative experiences with self-report questionnaires: Guilt and shame: State Shame and Guilt Scale - SSGS-3 (Marschall, Sanftner & Tangney, 1994) Conflict Coping Styles: Narratives Conflict Style Inventory NCSI (Behrendt, 2008) TEMPLATE DESIGN © 2008 www.PosterPresentations.com Passiveaggressive The findings emphasize the differential effect of guilt and shame on coping with conflict and the adaptive contribution of guilt, in comparison to shame, to cooperative coping. Theoretically, the study creates an interdisciplinary connection between personality psychology, the psychology of emotions, and the field of conflict research, in a manner that may deepen insight into personal behavior in conflict situations. Methodologically, this research emphasizes the importance of studying a complex phenomenon such as interpersonal conflict using qualitative experiences that enable participants to call up the emotions, thoughts and actions that accompanied the events, and offers tools for content analyzing the experiences of guilt and shame and styles of coping with conflict. Practically, this work deepens the understanding of the role of emotions in interpersonal conflict, which can advance more constructive practices for managing and resolving conflicts. 90% 80% 70% References 60% Barry, B., Smithy-Fulmer, I., & Goates, N. (2006). Bargaining with feelings: Emotionality in and around negotiation. In L. L. Thompson (Ed.), Negotiation Theory and Research (pp. 99-127). New-York: Psychology Press. 50% 40% 30% 20% Tangney, J. P., & Dearing, R. L. (2002). Shame and Guilt. New York: The Guilford Press. 10% 0% Guilt Shame Figure 2. Phenomenological differences between guilt and shame Concern for the other (χ² =28.63, df=1, p<.001) Concern for self (χ² =23.12, df=1, p<.001) Sense of exposure (χ² =13.61, df=1, p<.001) Personal responsibility (χ² =25.76, df=1, p<.000) Van Kleef, G. A., De Dreu, C. K. W., & Manstead, A. S. R. (2004). The interpersonal effects of anger and happiness in negotiations. Interpersonal Relation and Group Processes, 86(1), 57-76.