Titanic Bios 1st Class - Adams Memorial Library

advertisement

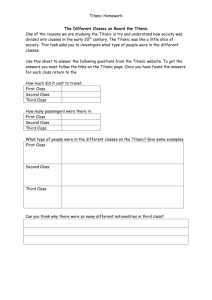

1 Helen Loraine Allison Hudson Trevor Allison Name: Miss Helen Loraine Allison Master Hudson Trevor Allison Born: Saturday 5th June 1909 Sunday 7th May 1911 Age: 2 years 10 months and 10 days. 11 months and 8 days. Last Residence: in Montreal Québéc Canada 1st Class passenger First Embarked: Southampton on Wednesday 10th April 1912 Ticket No. 113781 , £151 16s Cabin No.: C22/26 Died in the sinking. Wednesday 7th August 1929 Miss Helen Loraine Allison, 2, was travelling with her father Hudson Allison , her mother Bess and brother Trevor . After the collision Trevor went missing with his nurse Alice Cleaver . When the Allisons realized that Alice Cleaver and baby Trevor were unaccounted for, they resolved that they would not leave the Titanic until after Trevor was found, nor would they be parted from little Loraine, they were last seen standing together, smiling, on the promenade deck. Loraine Allison was the only child in first and second class to die (53 of 76 children in third-class perished). Mr. Allison was on the board of the British Lumber Corporation, and sailed to England for a directors' meeting. While 2 there, they had Trevor baptized at Epworth in the church where Methodist Founder John Wesley had preached. They took a side trip to the Scottish Highlands where Hudson bought two dozen Clydesdales and Hackney Stallions and mares for the stock farm. At the same time, they picked up furniture and recruited household staff for their two residences - George Swane was hired as a chauffeur, Mildred Brown as a cook, Alice Cleaver as a nursemaid for Trevor and Sarah Daniels as a Lady's maid for Bess. Like many others, the Allisons had altered travel plans to sail back with old friends on Titanic . They paid £151 16s for three cabins on the Upper Deck C-22/24/26. (ticket number113781). Mr and Mrs Allison were in one suite, Sarah Daniels and Loraine in another and Alice Cleaver and Trevor in the third. The other household servants travelled second class . On the last night of their lives, Hudson and Bess Allison sat down to dinner with Major Peuchen and Harry Molson , and Bess brought Loraine briefly into the Jacobean dining room so she could see how pretty it was. When the Titanic hit the iceberg, Alice Cleaver took Trevor and left with him in lifeboat 11 . Bess Allison was put in a boat with Loraine, but refused to leave the ship without her baby. She dragged Loraine out of the boat and started searching for Alice and Trevor. "Mrs Allison could have gotten away in perfect safety," Major Arthur Peuchen told the Montreal Daily Star "But somebody told her Mr Allison was in a boat being lowered on the opposite side of the deck, and with her little daughter she rushed away from the boat. Apparently she reached the other side to find that Mr Allison was not there. Meanwhile our boat had put off." Bess, Hudson and Loraine perished in the disaster. Brave Nurse and the Babe She Saved Miss Alice Catherine Cleaver, 22. While she was still in her teens Alice started working as a nursemaid to fashionable English families. She was hired by Montreal millionaires Hudson and Bess Allison as a last minute replacement to look after their baby son, Trevor. She boarded the Titanic at Southampton in first class under the Allison's ticket (No. 113781). After the collision on the night of 14th April 1912, Alice apparently bundled up the infant in her charge and went off to Second Class to round up the rest of the Allison household. Alice boarded lifeboat 11. Bedroom Steward William Faulkner held baby Trevor while Alice got in. Although there is no firm evidence it seems certain that the Allisons were unaware that Cleaver had taken the child off safely . The next day, Alice Cleaver and Sarah Daniels realized that they, along with Trevor and the cook - Mildred Brown, were the only survivors of their party. When she arrived in New York with the child, Alice avoided talking to reporters by telling them her name was Jean Lucile Carter William Carter 3 Name: Miss Lucile Polk Carter and `` William Thornton II Carter Born: Thursday 20th October 1898 Friday 14th September 1900 Age: 13 years 11 years Last Residence: in Philadelphia Pennsylvania United States 1st Class passenger First Embarked: Southampton on Wednesday 10th April 1912 Ticket No. 113760 , £120 Cabin No.: B96/98 Rescued (boat 4) Disembarked Carpathia: New York City on Thursday 18th April 1912 Died: Friday 19th October 1962 Monday 28th January 1985 Sunday, April 14, 1912 1:00 p.m. I, William Thornton II Carter have been on the Titanic for four days now. I boarded the Titanic at Southhampton, England on April 10. I am traveling with my family my father William Ernest Carter, my mother Lucile and my sister Lucile and we are in first class cabins B-96 and 98. We took this trip to go on a vacation and thought what better way to take a vacation than on the biggest and newest ship. When I saw the outside my jaw dropped “I’ve never seen anything bigger than this.” I heard a crew member say that it was 882 feet long. When I saw the inside of the ship I thought I was in a dream because I have never seen something so elegant. Another crew member said it had enough food to feed a small town. When I first came to my room I walked up the 1st class staircase I thought there is no way they could have this on a boat. The staircase was inspired by the French court of Louis IV said a lady as I walked upstairs. When I walked into our 1st class rooms I thought I was the richest person in the world because of how beautiful of a room I was staying in. I visited the open deck space and met a couple of other 1st class passengers. When I walked out onto the deck space I was amazed by how big it was. My family and I ate at the 1st class restaurant. I liked it because I had Filet Mignons Lili Saute of Chicken and that is one of my favorite dishes. My favorite part of the ship is the open deck space because I get to meet all classes not just stuck with the 1st class passengers which can get boring because some of them are really snotty. My least favorite part of the ship is the 1st class stairway because people are always standing in it like they own it because they are 1st class. I have been hanging out in the gymnasium and on the open deck space with the other kids of all classes. Sincerely, William Thornton II Carter (WLTX) - April 15th, 2012 will mark 100 years since the tragic sinking of the Titanic. Between now and then, you will hear many stories about what happened that night. However, you may not know the story of South Carolina's only Titanic connection. A young woman survived the Titanic sinking and ended up living out her final years in Charleston. Her name was Lucile Carter, and she was only 14 when the disaster happened. Carter's granddaughter, Tessa Bowden, says her grandmother seldom talked about what happened that night. 4 "It was never discussed. It was the equivalent of the Holocaust to her." Lucile's father, William Carter, was a wealthy man for his day. He and his family enjoyed the finer things in life--large homes, cars, and servants. The Carters had it all, and that April, they planned a trip overseas. Tessa says, "I really think the Titanic was the biggest draw and the anticipation of coming back on the Titanic. While they were over there they traveled quite a bit. My great-grandfather got to get new polo ponies while he was there and he had an automobile, a Renault, made for himself. My grandmother was in boarding school in Switzerland and so it was easy to pick her up and at the same time." The Carters boarded the Titanic on April 10th, 1912. They were first class passengers, rubbing elbows with the rich and famous. But for Lucile, this was nothing new. "She was 14, it was just a matter of fact," Tessa says. "This is what they were going to do. She traveled a lot. When you're privileged like she was, you just take things for granted." Five days into the voyage, the Titanic hit an iceberg. Lucile and her family joined other first class passengers as they waited for the lifeboats to be lowered. It was supposed to be women and children only; however, with the last lifeboat being lowered, Carter's family still wasn't safe and time was running out. In all of the confusion, Tessa says her great-grandfather went to the other side of the ship where gentlemen were being allowed on a lifeboat. She's heard many stories about how he managed to survive that night, including this account. "The manager of the lifeboat, begged him to get in," says Tessa. "There were no other women and children in sight on the deck, so he got in. He got to the Carpathia much faster than my grandmother's boat did and he's standing on the deck of the Carpathia when she gets there and he's saying 'what took you so long, I thought you'd never get here. I just had the most wonderful breakfast.' That is a horrible story." With their marriage already on the rocks and believing her husband abandoned them on the Titanic, the Carters divorced and Lucile very seldom spoke of her father again. Like most Titanic survivors, Lucile was often asked to talk about what happened that night but seldom did. However, this is what she had to say during a rare interview on the 40th anniversary of the disaster. "If the Titanic sank only a week ago it couldn't be more vivid," Lucile said. "I was in the last lifeboat. It was almost carried under by the suction. I saw the whole ship sink, lighted deck by lighted deck, as the band played 'Nearer My God to Thee.' Then the explosion came. There was no moon that night, just millions of stars and the terrible calls for help." The memories of that night haunted Lucile for the rest of her life. As an adult, she shared very little about the disaster with her husband and three children and she really didn't like getting back in the water, but who could blame her? In her last days, Lucile ended up living next to the very ocean that claimed the Titanic, staying at 33 Society Street in Charleston. She moved there to be close to her daughter who lived in Summerville. Lucile's home was just yards from the water. Tessa says she did appreciate the beauty, but doesn't remember her itching to get back on boats. Six months after the 50th anniversary of the Titanic disaster, Lucile Carter passed away due to heart failure. She died peacefully in her sleep while visiting her daughter's home in Summerville. Mr. William Ernest Carter’s Story A resident of Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, Mr. Carter boarded the Titanic at Southampton as a first class passenger together with his wife Lucile Carter and their children Lucile and William. They held ticket no. 113760 (£120) and occupied cabins B-96 and 98. Also traveling were Mrs. Carter's maid Auguste Serreplan, Mr. Carter's manservant Alexander Cairns and, traveling in second class, Carter's chauffeur Charles Aldworth. Lying in the forward hold of the Titanic, and listed on the cargo manifest, was Carter's 25 horsepower Renault automobile. It is listed as a case so perhaps the car was not fully assembled. He also brought with him two dogs. He would later claim $5000 for the car and $100 and $200 for the dogs. On the night of 14 April the Carters joined an exclusive dinner party held in honor of Captain Smith in the à la carte restaurant. The host was George Widener and the party was attended by many notable first class passengers. Later, after the ladies had retired and Captain Smith had departed for the bridge, the men chatted and played cards in the smoking room. After the collision the Carters joined some of the other prominent first class passengers as they waited for the boats to be prepared for lowering. When William Carter had seen his family safely into lifeboat 4 he joined Harry Widener and advised him to try for a boat before they were all gone. But Harry replied that he would rather take a chance and stick with the ship. 5 Widener might well have taken Carter's advice, for he lost his life while Mr Carter was eventually able to escape. At around 2 a.m. he was standing near the officer's quarters. Collapsibles A and B remained lashed to the roof but boats C and D had been freed and were being loaded. At one point a group of men desperately tried to rush boat C. Purser Herbert McElroy fired his pistol and the culprits were removed. Loading with women and children progressed but eventually no more could be found and as the boat was released for lowering Carter and another man stepped in. The other passenger was Joseph Bruce Ismay. William Carter arrived at the Carpathia ahead of his family and waited on the deck straining to see boat 4 which held his wife and two children. When it finally arrived William did not recognize his son under a big ladies hat and called out for him, according to some sources John Jacob Astor had placed the hat on the boy and explained that he was now a girl and should be allowed into the boat, other sources suggest, the more likely scenario that it was his mother in response to Chief Second Steward George Dodd's order that no more boys were to enter lifeboat 4. Vera Dick Name: Mrs Vera Dick (née Gillespie) Born: Tuesday 12th June 1894 Age: 17 years 10 months and 3 days. 1st Class passenger First Embarked: Southampton on Wednesday 10th April 1912 Ticket No. 17474 , £57 Cabin No.: B20 Rescued (boat 3) Disembarked Carpathia: New York City on Thursday 18th April 1912 Died: Sunday 7th October 1973 Mrs. Albert Adrian Dick (Vera Gillespie), 17, was born in Calgary, Alberta, 12 June 1894, the daughter of Frederick William Gillespie and his wife Annie. Vera Gillespie married Albert Adrian Dick on 31 May 1911. They boarded the Titanic at Cherbourg as first class passengers (Cabin B-20, ticket number 17474, £57). Aboard ship, one of the younger stewards, a man by the name of Jones, took a shine to Vera, and much to Bert's annoyance, Vera flirted with him. They were also befriended by Thomas Andrews, and on the last night of the voyage the Dicks shared his table at dinner. Vera Dick was to say afterwards that she would always remember the stars that night. "Even in Canada where we have clear nights I have never seen such a clear sky or stars so bright." The Dicks were getting ready for bed when the ship hit the iceberg, and felt nothing. They were made aware of the accident when the same steward who had taken a shine to Vera knocked on their door and told them to dress. "We would have slept through the whole thing if the steward hadn't knocked on our door shortly after midnight and told us to put on our lifejackets," Mrs. Dick told a Calgary newspaper. Both were escorted to lifeboat 3 by Thomas Andrews who saw them off. According to Bert, he his wife were locked in a farewell embrace, when he was pushed into the lifeboat with her. As the boat jerked towards the water, the Dicks wondered whether it might not capsize and whether they might not be safer had they not left the ship. When they returned to Calgary, Bert was ostracized because he had survived. His name was tarnished by gossip that he had dressed as a woman to get off the ship. His hotel business suffered, so he sold it and continued to make money in real estate. Vera studied music at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Toronto, and was well known as a vocalist in Calgary. 6 Vera Dick (née Gillespie) died in Banff, Alta. on 7 October 1973. WOMAN SURVIVOR HEARD SHOOTING New York Herald Friday 19 April 1912 One of the most comprehensive and connected stories of the disaster was that recounted by Mrs. A. A. Dick, wife of a merchant in Calgary, Canada. "We were awakened in our cabin on hearing the crash. Together with my husband I made my way to one of the decks and learned that the steamship had struck an iceberg. We could see the iceberg. The night was clear and the sky was filled with stars. "We were indifferent about leaving the steamship as we did not believe it was going to sink. We got off in the third boat. We had not gone far when we realized the big liner was sinking. Then, at a safe distance, away from the possibility of suction, we saw one deck after another sink from view. We could see men jumping into the water and could hear terrifying screams and shouts of distress. "We heard several rounds of shots echoing across the water and learned afterward that many men were shot down as the last boat put away. There were three men shot in the steerage by the second or third officer, we understand. As the steamship went down the band was up forward and we could faintly hear the start of 'Nearer My God to Thee.' "There was no evidence of panic while we were on board and I first laughed at the idea of the Titanic sinking. We were to the open boat for more than six hours, but had bread and water with us. We thought aid was never coming and we suffered from the cold." Washington Dodge, Jr. Name: Master Washington Dodge, Jr. Born: Monday 23rd September 1907 Age: 4 years 6 months and 23 days. Last Residence: in San Francisco California United States 1st Class passenger First Embarked: Southampton on Wednesday 10th April 1912 Ticket No. 33638 , £81 17s 2d Cabin No.: A34 Destination: San Francisco California United States Rescued (boat 5) Disembarked Carpathia: New York City on Thursday 18th April 1912 Died: Tuesday 3rd December 1974 DR. DODGE GIVES STORY OF RESCUE The Bulletin San Francisco, April 20, 1912 NEW YORK, April 20.–“At 10 p.m. Sunday while my wife and I went out for a stroll along the Titanic’s promenade deck we found the air icy cold–so cold, in fact, that we were driven inside although we had on heavy 7 wraps. This change of temperature had occurred in the previous two hours. We went to bed and were awakened about 11:40 by a jar which gave me the impression that a blow on the side had moved the entire vessel laterally to a considerable angle. With only my overcoat and slippers, I went through the companion way, but, to my surprise, found no one seriously considering the shock. “Men in evening clothes stood about chatting and laughing, and when an officer–I did not know his name–hurried by I asked, ‘What is the trouble?’ He replied: ‘Something wrong; something is wrong with the propeller; nothing serious.’ “I went back to my stateroom, where my wife had already arisen to dress herself and I dissuaded her from dressing herself or our four-year-old son. A little while later, still feeling nervous, I went up to the promenade deck and there saw a great mass of ice close to the starboard rail. Going back to my cabin again, I met my bedroom steward, with whom I had crossed the ocean before, who whispered to me that ‘Word has come from down below for everyone to put on life preservers.’ “I rushed back to my stateroom and told my wife the news and made her come up on deck with the baby, even half clothed. The boats on the starboard side were then suspended from the davits, but no passengers wanted to get in. “It was a drop of fifty feet to the surface of the sea, and, apparently everybody considered that they were safer on the ‘unsinkable Titanic’ than in a small boat whose only propelling power was four oars. The first boat was only half filled, for the simple reason that no one would get aboard. “Personally, I waited for the lifeboat to become filled, and then saw there was plenty of room I asked the officer at the rail, whose name I do not know, why I also could not get in, as there was plenty of room. His only reply was, ‘Women and children first,’ and the half-filled boat sheered off. “Before the next boats were lowered passengers who had become excited were calmed by the utterances of the officers that the injury was trivial and that in case it proved serious at least four steamships had been summoned by wireless and would be on hand within an hour. I watched the lowering of the boat in which my wife and child were until it was safely launched on an even keel, and then I went to the starboard side of the ship, where the boats with the odd numbers from one to fifteen were being prepared for dropping over the side. “The thing that impressed me was that there was not sufficient men to launch the boats, and, as a matter of fact, when the ship went down there was still one boat on the davits and one on the deck. “The peculiar part of the whole rescue question was that the first boats had no more than thirty passengers, with four seamen to row, while the latter boats averaged from forty to fifty, with hardly one person aboard who knew how to move an oar. “All this time the Titanic had a slight list to port, but just after the collision Captain Smith, coming hurriedly up and inquiring what the list was and finding it eighteen degrees to starboard, said ‘My God!’ ” As there is always a touch of humor in the most gruesome of happenings, it is told by Mrs. Dodge that one of the sailors in the boat in which she embarked insisted on taking off his shoes and giving her his stockings, saying: “I assure you, m’am, that they are perfectly clean. I just put them on this morning.” “I waited until what I thought was the end,” continued Dr. Dodge. “I certainly saw no signs of any women or children on deck when I was told to take a seat in boat number thirteen. When lowered we nearly came abreast of the three-foot stream that the condenser pumps were still sending out from the ship’s side. We cried out and the flow halted. I cannot image how that was done. “Another danger to us was that the boat in which [Bruce] Ismay escaped was lowered, owing to the angle of the sinking ship, almost directly above us. If it had come ten feet farther both boats would have gone to the bottom, but our yells and cries stopped this catastrophe also. “When boat number [thirteen] was being lowered from the ‘A’ deck it stayed there for at least two minutes while the officers in charge were calling for more women and children. But as none responded the officers said (and I am sorry I do not know their names) ‘some of you men tumble in,’ and I ‘tumbled.’ “In my boat when we found ourselves afloat we also found that the four oars were secured with strands of tarred rope. No man in the crowd had a pocket knife, but one had sufficient strength in his fingers to tear open one of the strands. That was the only way in which we got our boat far enough away from the Titanic’s side to escape the volume of the condenser pumps. “Here is another thing that I want to emphasize; only one of all the boats set adrift from the vessel’s side had a lantern. We had to follow the only boat that had one, and if it had not been for that solitary lantern possibly many of the other boats might have drifted away and gone down. “To show how lightly even the executive officers of the ship took the matter of the collision is proven by the fact that the officer in charge of the boat in which my wife was saved refused to let his men row more than half a mile from the 8 Titanic because that he would soon have orders to come back. “We saw the sinking of the vessel. The lights continued burning all along its starboard side until the moment of its downward plunge. After that a series of terrific explosions occurred, I suppose either from the boilers or weakened bulkheads. “And then we just rowed about until dawn when we caught sight of the port light of the Carpathia, and knew that we were saved. “One curious point I noticed is that the first two boats launched held only their crews. Half an hour later I was told by an officer that they were launched in that shape to stand by in case of accident to her small boats. “But there were no accidents and practically nothing for these boats to do, so many valuable lives were lost. “If a sea had been running I do not see how many of the small boats would have lived. For instance, on my boat there were neither one officer or a seaman. The only men at the oars were stewards, who could no more row than I could serve a dinner. “While order prevailed until the last lifeboat had been lowered, hell prevailed when the officers, who had kept the steerage passengers below, with their revolvers pointed at them to prevent them from making their way to the upper deck. “When the steerage passengers came up many of them had knives, revolvers and clubs and sought to fight their way to the two unlaunched, collapsible boats. Many of these were shot by the officers. “Only one of the rafts floated, and even that did not float above the water’s edge. From 40 to 50 persons who had jumped overboard clambered aboard it and stood upon it, locked arm and arm together until it was submerged to a depth of at least 18 inches. They all tried to hold together, but when the Carpathia’s boat reached them there were only 16 left. “The most horrible part of the story is that statement that several persons in the lifeboats saw, when the Titanic took her final plunge, that her four great smokestacks sucked up and carried down in their giant maws dozens of the third class passengers, then huddled together on the forward upper deck.” DR. DODGE'S WIFE TELLS STORY OF TITANIC WRECK Seated in the library of her home on Washington street, amid a profusion of flowers sent by friends to express their welcome home, Mrs. Washington Dodge again told the story of her experiences on the night the ill-fated Titanic went down. Dr. and Mrs. Dodge and their 5-year-old son, Washington Dodge Jr., arrived in the city yesterday afternoon, little the worse for their experience. The parents' one anxiety is for the boy, who is seriously ill from the effects of the exposure to the ice-chilled air on the night of the disaster. "Was it cold?" said Mrs. Dodge. "You can imagine how cold it was when I tell you that we passed fifty-six miles of icebergs after we got on the Carpathia . The baby had nothing on but his pajamas and a life preserver. "I think it is foolish to speak of the heroism displayed. There was none that I witnessed. It was merely a matter of waiting your turn for a lifeboat, and there was no keen anxiety to enter the boats because everybody had such confidence in that wretched ship. The officers told us that they had wireless communication with seven vessels, which were on the way to relieve us, and the men believed themselves as safe on board as in the boats. It seemed the vaguest possibility that the ship might sink before one of the seven vessels arrived. "Of course, I left the Titanic before it began to settle into the water. The steerage passengers had not come on deck. In fact, there were few on the deck from which we left and more men than women. "It happened this way. There seems to have been an order issued that all women should congregate on the port side of the vessel. The vessel was injured on the starboard side, and even when I left the ship there was a slight list to starboard. We did not hear this order. I was in my stateroom, had retired again after the accident when the doctor came saying he had met our steward and had been told to get into a life preserver. I slipped on my fur coat over my night robe and preserver, put on my shoes without stockings; I did not stop to button them. "We had made a practice of sitting on the starboard side of the deck, the gymnasium was there, and naturally when we went above we turned to starboard. They were lowering boats. I entered the second boat with my baby. This boat had an officer in command, and enough officers to man the oars. Several women entered with me and as we commenced to lower the boat the women's husbands jumped in with them. I called to the doctor to come, but he refused because there were still a few women on deck. Every woman in that second boat with the exception of myself, had her husband with her. "I supposed all the women were congregated on the port side because it would naturally be the highest side, and the safest because [it would be] the last to go down. We had no idea then that there would not be enough boats to go around. In fact, the first boats were only half filled. 9 "There must have been some confusion in orders, else I do not see why some of the women were not sent from port to starboard to enter those boats being lowered there. My husband got into the thirteenth boat. At that time there were no women on the starboard side. There was not one women in the boat he entered, and no member of the crew. "Bruce Ismay entered the fifteenth boat from starboard. It was being lowered at the same time, and the doctor says he remembers this because there was some fear that the boats might swing into each other as they were lowered down the side of the vessel. "The most terrible part of the experience was that awful crying after the ship went down. We were a mile away, but we heard it–oh, how we heard it. It seemed to last about an hour, although it may have been only a sort time, for some say a man could not have lived in that water over fifteen minutes. At last it died down. "Our officer and the members of the crew wanted to go back and pick up those whom they could, but the women in the boat would not left them. They told them if they attempted to turn back their husbands would take the oars from them, and the other men outnumbered the crew. I told them I could not see how they could forbid turning back in the face of those awful cries. I will remember it until I die, as it is. I told them: 'How do I know, you have your husbands with you, but my husband may be one of those who are crying.'" "They argued that if we got back where the people were struggling, some of the steerage passengers, crazed with fear and the cold, might capsize the boat struggling to get it, or might force the officers to overload so we would all go down." "After the crying died down, tow or three of the women became hysterical–about what I don't know; they were missing none of their people. I was trying to keep baby from realization of what was happening, but when these women shrieked he would begin crying and asking, 'Where's papa?' "Finally I did what everyone thinks a strange thing. I changed lifeboats in mid ocean. We overtook the first boat. It was hardly half filled. They offered to take any of us aboard, and to get away from the hysteria of the others I changed. "The most pathetic thing was the scene on board the Carpathia during the rescue. As each boat drew up the survivors would peer over, straining to see the face of someone they had left behind. They were the young brides – everybody on board, of course, had known they were brides, and they had watched them laughing and promenading with their husbands. "The moans of anxiety and disappointment as each boat failed to bring up those that they were looking for were awful and finally that awful despair which fell over everyone when we knew there were no more boats to pick up. "Still they would not give up hope. "'Are you missing anyone?' the passengers would ask each other, never 'Have you lost anyone?' "Too much cannot be said of the kindness of the Carpathia's passengers. They gave up staterooms, they took the very clothing off their bodies for us. I left the Carpathia wearing garments given me by a women whose name I do not know and will never know." She exhibited the bloomer trousers she had cut for Baby Dodge from a blanket given her by a sailor. "I am sorry that I knew the names of so few passengers. There were two men aboard particularly, who every day used to come on the sun deck to play with the baby, and we often fell into conversation. Those men were not among the survivors. I do wish I h ad known their names that I might tell their wives some of the beautiful things they had said to me of their home life, casually, in these conversation." Jean Hippach Name: Miss Jean Gertrude Hippach Born: Sunday 30th September 1894 Age: 17 years Marital Status: Single. Last Residence: in Chicago Illinois United States 1st Class passenger 10 First Embarked: Cherbourg on Wednesday 10th April 1912 Ticket No. 111361 , £57 19s 7d Cabin No.: B18 Rescued (boat 4) Disembarked Carpathia: New York City on Thursday 18th April 1912 Died: Thursday 14th November 1974 Miss Jean Gertrude Hippach, 16, was born in Chicago, IL, the daughter of Louis Albert Hippach and Ida Sophia Fischer. Jean had been touring Europe with her mother. They boarded the Titanic in Cherbourg as first class passengers. They occupied cabin B-18. Jean slept through the collision, awaking when the steam began roaring through the funnels. Jean and her mother were rescued in Lifeboat 4. Mrs. Hippach was traveling abroad with her daughter, Jean Hippach, trying to recover from the loss of two sons in the Iroquois Theater fire. The two ladies boarded the Titanic in Cherbourg, traveling first class. They later claimed they had not wanted to board the ship, not trusting a maiden voyage but White Star employees had told them that there was only one First Class cabin left, implying that everyone wanted to go on the ship. They felt lucky to get their ticket, only to discover that the ship was only partially full. They traveled with ticket 111361 (£57 19s 7d) in cabin B-18. "Everyone was saying Sunday evening that we were ahead of schedule and that we would break the records." Mrs. Hippach and her daughter were asleep when the Titanic struck the iceberg. Ida Hippach thought the shock of the collision was mild. Her daughter continued sleeping until the roar of the steam escaping through the funnels woke her. They put on their wraps and rushed out into the corridor. They heard everybody asking, "What is that? Did you hear that?" 11 Ida Hippach heard someone say that they hit an iceberg, but no one was alarmed or thought there was any danger. She decided to go out onto deck because she wanted to see the iceberg as she had never seen one. An officer, walking past, told them to return to their room. "Ladies, go back to bed. You'll catch cold." They went back to their stateroom, but decided to dress and go back out into the corridor. They were told to return to their room and get a lifebelt. Mrs. Hippach and her daughter came onto deck as they were lowering a lifeboat. They thought they would be safer on the Titanic, so didn't get into one of the earlier boats. They watched the officer try to get people into Boats 2 and 6, noting how few people were in each as they were lowered. Passengers talked to each other, at first saying the boat was in no danger. Then they were told the boat would stay afloat for at least 24 hours and that they were safer on deck than in the lifeboats. Later, they were told that the Olympic was near and some ship's lights were pointed out to her. Mrs. Hippach had no clue that there were not enough lifeboats. They were walking by Lifeboat 4 as it was being loaded and Colonel Astor told them to get in, although he said there was no danger. Ida and her daughter clambered through the windows and entered the boat, finding that it had a couple of sailors. The boat got a small amount of water in it and a man that Mrs. Hippach thought was a third class passenger jumped into the boat (although this was probably a crew member). The women had to help row away from the Titanic. Ida Hippach now knew the Titanic was sinking because the portholes were so near to the water. She heard someone calling for the boat to return to pick up more passengers, but they did not dare. From their position, about 450 feet from the ship, they heard a "fearful explosion" and watched it split apart. They rowed away, expecting the suction to pull at them. The lights all went out one by one then they all went out in a flash, except for a lantern on a mast. There was a fearful cry from the people in the water. They rowed back and were able to pick about eight men out. In the morning they saw the Carpathia and they rowed about two miles to the ship. Mrs. Hippach was taken aboard in a swinging seat. 'My, but it was good to be taken aboard and nursed.' It was uncertain at first whether they were saved, however by April 17 the Chicago papers announced their rescue. A son, who worked for an engineering firm in North Carolina, and Mr. Hippach travelled to New York City to meet the Hippach women. They arrived in Chicago on April 21, 1912 aboard the Twentieth Century Limited. ASTOR SAVED US, SAY WOMEN New York Times Monday 22 April 1912 Mrs. Ida S. Hippach and her daughter, Jean, survivors of the Titanic, who arrived home to-day, said that they were saved by Col. John Jacob Astor, who forced the crew of the last lifeboat to wait for them. "We saw Col. Astor place Mrs. Astor in a boat and heard him assure her that he would follow later," said Mrs. Hippach. "He turned to us with a smile and said `Ladies, you are next.' The officer in charge of the boat protested that the craft was full and the seamen started to lower it. Col. Astor exclaimed 'Hold that boat,' in the voice of a man to be obeyed, and the men did as he ordered. The boat had been ordered past the upper deck, and the Colonel took us to the next deck below and put us in the boat, one after the other, through a porthole." Mrs. Hippach said that after the impact the Titanic lay broadside on an iceberg that seemed, she said, to be a hundred feet high and extended farther than she could see. Mary Lines Name: Miss Mary Conover Lines Born: Saturday 27th July 1895 Age: 16 years Marital Status: Single. Last Residence: in Paris France 1st Class passenger First Embarked: Cherbourg on Wednesday 10th April 1912 Ticket No. 17592 , £39 8s Cabin No.: D28 Rescued (boat 9) 12 Disembarked Carpathia: New York City on Thursday 18th April 1912 Died: Sunday 23rd November 1975 Mrs. Ernest H. Lines (Elizabeth Lindsey James), was born in 1861, in Burlington, New Jersey, the daughter of Benjamin L. James and Anne Langstrom. Mrs. Lines' husband, Dr Ernest H. Lines, was President of the New York Life Insurance Company. They had lived for many years in Paris, France. In April 1912, Elizabeth and her daughter, Mary, were traveling to the United States to attend her son's graduation from Dartmouth College. They boarded the Titanic at Southampton as first class passengers and occupied cabin D-28. On Saturday April 13th, the two ladies had just finished luncheon in the first class dining room on D Deck, they had made a habit to stop for coffee in the adjoining reception room. After she had taken a seat, Captain Smith and Bruce Ismay came and sat at a table nearby, and began discussing the possibility of having the last boilers lit. Mrs. Lines recognized Mr. Ismay from several years back when they had both lived in New York, and she confirmed his identity with her table steward. During the sinking, an officer tied lifebelts on Mrs Lines and her daughter, saying: "We are sending you out as a matter of precaution. We hope you will be back for breakfast." The two ladies were rescued in lifeboat 9. In 1919 Mary married to Sargeat Holbrook Wellman. They settled in Topsfield, Massachusetts and had a daughter and two sons. Mary Wellman (née Lines) died November 23, 1975, at her home in Topsfield. Mary C. Wellman, a survivor of the liner Titanic, died Sunday at her home. She was 80 years old. Mary Lines Wellman When Mrs. Wellam was 16 and studying in Paris, her father booked passage for her and her mother on the White Star line ship. They were to attend Dartmouth College graduation. On the night of April 14, 1912, about 1,600 miles east of New York, the ship struck an iceberg, tearing a 300-foot gash in the hull. “I was just dozing off when I felt a jarring crash,” said Wellman later. “We ran upstairs and someone steered us to a lifeboat. The ship was listing then and some lifeboats had been lowered, but many people were refusing to get in them. The deck was covered with ice.” “I particularly recall the British seamen were magnificent. They knew, of course, that they would lose their lives, but they calmly and carefully doled out blankets and biscuits to us as we got into a lifeboat.” Official reports said the 682-foot ship went down bow first about 2 ½ hours after the crash. The ship’s orchestra assembled on the sloping deck and played to calm the passengers. “At about 2 o’clock the huge ship sank with a dreadful noise and the orchestra played to the very end,” Mrs. Wellman said. “So we sat all night in the freezing dark. Some women tried to row to keep warm, but we didn’t want to get too far away from our location.” The Cunard line Carpathia heard the Titanic’s SOS and raced 58 miles to the rescue, picking up 705 survivors at dawn. At about 5:30 A.M., our savior, the Carpathia, came into view,” Mrs. Wellman said. “It looked so small in comparison to the tremendous Titanic.” Georgette Madill (16) Georgette Madell boarded the Titanic at Southampton as a first class passenger. She traveled with her mother, Mrs. Edward Scott Robert and her cousin Miss Elisabeth Walton Allen with whom she shared cabin B-5. The event s of April 15, 1912 were described by Miss Allen. "As 13 the Titanic plunged deeper and deeper we could see her stem rising higher and higher until her lights began to go out. As the last lights on the stern went out we saw her plunge distinctively, bow fist and intact. Then the screams began and seem to last eternally. We rowed back, after the Titanic was under water, toward the place where she had gone down, but we saw no one in the water, nor were we near enough to any other lifeboats to see them... "Our boat was the first one picked up by the Carpathia. I happened to be the first one up the ladder, as the others seemed afraid to start up, and when the officer who received me asked where the Titanic was, I told him she had gone down." Jack Ryerson Emily Ryerson Name: Master John Borie “Jack” Ryerson Miss Emily Borie Ryerson Born: Friday 16th December 1898 Sunday 8th October 1893 Age: 13 years 18 years 6 months and 7 days Last Residence: in Cooperstown New York United States 1st Class passenger First Embarked: Cherbourg on Wednesday 10th April 1912 Ticket No. 17608 , £262 7s 6d Cabin No.: B57/63/66 Rescued (boat 4) Disembarked Carpathia: New York City on Thursday 18th April 1912 Died: Tuesday 21st January 1986 Saturday 25th June 1960 The sinking of the Titanic (1912) by Jay Henry Mowbray Standing at the rail of the main deck of the ill-fated Titanic, Arthur Ryerson, of Gray's lane, Haverford, Pa., waved encouragement to his wife as the lifeboat in which she and her three children — John, Emily and Susan — had been placed with his assistance glided away from the doomed ship. A few minutes later, after the lifeboat with his loved ones had passed beyond the range of his vision, Mr. Ryerson met death in the icy water into which the crushed ship plunged. It is now known that Mr. Ryerson might have found a place in one of the first lifeboats to be lowered, but made no effort to leave the ship's deck after assuring himself that his wife and children would be saved. It was not until the Carpathia reached her dock that relatives who were on hand to meet the survivors of the Ryerson family knew that little "Jack" Ryerson was among the rescued. Day by day since the first tidings of the accident to the Titanic were published, "Jack" had been placed among the missing. Perhaps of all those who came up from the Carpathia with the impress of the tragedy upon them, the homecoming of Mrs. Ryerson was peculiarly sad. While motoring with J. Lewis Hoffman, of Radnor, Pa., on the Main Line, on Monday a week before, Arthur L. Ryerson, her son, was killed. His parents abandoned their plans for a summer pleasure trip through Europe and took passage on the first home-bound ship, which happened to be the Titanic, to attend the funeral of their son. And now upon one tragedy a second presses. Mrs. Ryerson said that she and her husband were asleep in their staterooms, as were their children, when the terrible grating crash came and the ship foundered. The women threw kimonos over their night gowns and rushed barefooted to the deck. Master Ryerson's nurse caught up a few articles of the little boy's clothing and almost as soon as the party reached the deck they were numbered off into boats and lowered into the sea. 14 Douglas Spedden Name: Master Robert Douglas Spedden Born: Sunday 19th November 1905 Age: 6 years Last Residence: in Tuxedo Park New York United States 1st Class passenger First Embarked: Cherbourg on Wednesday 10th April 1912 Ticket No. 16966 , £134 10s Cabin No.: E40 Destination: Tuxedo Park New York United States Rescued (boat 3) Disembarked Carpathia: New York City on Thursday 18th April 1912 Died: Sunday 8th August 1915 Cause of Death: Road Traffic Accident (RTA) Robert Douglas Speeden playing spin the top on the promenade deck of Titanic Master Robert Douglas Spedden was born in New York City on 19 November 1905, the only child of Frederic Oakley Spedden and Daisy Spedden. The family lived in Tuxedo Park, NY. In late 1911, Douglas accompanied his parents when they sailed for Algiers on the Caronia. He was attended by his private nurse, Elizabeth Burns, whom he called "Muddie Boons," because he had trouble pronouncing her name. From Algiers the family moved on, first to Monte Carlo and later to Paris. On April 10th the family boarded a train from Paris to Cherbourg where they were to board Titanic. The harbor at Cherbourg was too small to berth the Olympic and Titanic which had to moor offshore. First and second class passengers were taken on a specially built tender ship, the SS Nomadic. The journey took between half an hour and forty five minutes and passengers expected the same standards of luxury as they would encounter on the main vessel. The Speddens were in the company of some of the richest people in the world, including Colonel John Jacob Astor and his new wife, Madeleine, Benjamin Guggenheim and his entourage and the famous Unsinkable Molly Brown. Douglas, and presumably Muddie Boons, occupied cabin E-40. Douglas’ parents described being woken by a sudden shock and the noise of the engines grinding. Daisy and Frederic Spedden went up on deck to find out what was happening. Daisy described in her diary how the ship was already tilting so she went to waken her son, his nanny and the maid. Muddie told him that they were taking a "trip to see the stars." An hour after the collision, Mrs. Spedden, the two servants and Douglas were helped into lifeboat number 3 by a member of the crew. Since there were no other women and children in sight, Frederic Spedden was permitted to take a place along with twenty other men. After Titanic sank, the passengers on board lifeboat number 3 tried to persuade the crew member in charge to go back in order to rescue people from the water but he was worried that the small craft would be pulled under by the suction created by the sinking . The family group waited for the rescue ship to arrive, huddled together against the cold. Douglas must have been relatively unconcerned by the unfolding ordeal 15 because it is reported that he slept aboard the lifeboat until dawn broke. When he woke at dawn he saw the icebergs all around and exclaimed "Oh, Muddie, look at the beautiful North Pole with no Santa Claus on it." Daisy Spedden wrote to a friend in Madeira about a fellow lifeboat passenger who “never stopped talking and telling the sailors what to do as she imbibed from a brandy flask frequently, never offering a drop to anyone else.” Once aboard the Carpathia the Speddens were remembered by other passengers for their kindness in looking after others. Carpathia’s Captain, Arthur Rostron had particular words of praise for how the Spedden family conducted themselves during the journey into New York. Following the Titanic disaster, they continued to travel to Europe much as before but with a new perspective on the frailty of life. Daisy wrote that all the values of their lives had changed and “the daily incidents which once seemed of such importance to us dwindled into mere trivialities". Sadly that perspective was brought very much into focus three years later. While the family was spending the summer in Maine, Douglas, now aged nine, ran out into the road after a ball and was hit by a car and killed. He was an only child. No-one knows what happened to Polar the Teddy Bear. Douglas’s mother stopped writing her diaries. The couple had no other children. Frederic died in 1947 and Daisy just three years later. Young Douglas is immortalized in Titanic history as the little boy playing with a spinning top on the deck of Titanic. This is a photograph taken by Jesuit priest, Father Francis Browne and published in his collection. The photograph was also brought to life in James Cameron’s film, Titanic. He also appears in a photograph taken on Titanic’s promenade deck in which he is looking out to sea while a crew member poses in the foreground. But the main memory of Douglas Spedden is recorded in the children’s book, “Polar, the Titanic Bear” which was written for Douglas by his mother as a present at Christmas in 1913. It recounts the adventures of the boy’s beloved white teddy bear, Polar who was with him on Titanic. Daisy designed the cover illustrations herself. It was republished in 1994 by Madison Press after a family member discovered it amongst Daisy’s belongings. Jack B. Thayer, Jr. Name: Mr John “Jack” Borland Thayer, Jr. Born: Monday 24th December 1894 Age: 17 years Last Residence: in Haverford Pennsylvania United States Occupation: Scholar 1st Class passenger First Embarked: Cherbourg on Wednesday 10th April 1912 Ticket No. 17421 , £110 17s 8d Cabin No.: C70 Rescued (boat B) Disembarked Carpathia: New York City on Thursday 18th April 1912 Died: Thursday 20th September 1945 16 Tragic Night On The Sea Hanford Sentinel by Doris Robertson Polley Jack wrote a small, practically pamphlet sized, book about that terrible maritime disaster. The booklet titled "The Sinking of the S.S. Titanic" was published in 1940 and again in 1974 by 7C's Press, Inc., and it contained only 31 pages, including sketches and photos. The author wrote the account primarily as a family record in memory of his father John Borland Thayer III, who lost his life in the disaster. The record has finally reached the West Coast branch of the family after all these years. If you saw the movie or have read about it you already know that the date was April 14-15, 1912 when the huge "unsinkable luxury liner" hit an iceberg and sank. The ship was carrying 2,208 persons. Only 703 managed to leave the ship in the lifeboats, leaving 1.553 to go down with the ship. Of those left behind, 42 were saved. Jack Thayer was one of the 42. Going back to the beginning of the story, Jack was only 17 and perhaps it was the fact that he was young and athletic that he survived. He had boarded the ship for its maiden voyage along with his father, who was then first vice-president of the Pennsylvania Railroad, and his mother Marian Longstreth Thayer in Southampton, England. with them was Mrs. Thayer's maid Margaret Flemming. On the crossing, the family had two first-class staterooms. Heading into the channel out of Southampton, the Titanic broke the moorings of another ship docked nearby. It was the S.S. Oceanic. Suction of the Titanic screws caused the Oceanic's stern to swing out into the channel within a yard or two of striking the Titanic. This near accident, as Jack wrote, was considered an "ill-omen by all those accustomed to the sea." He describes the luxurious dining and the social conversations with several prominent families as well as Thomas Andrews, one of the ship's designers; Archie Frost, the builders' chief engineer; at least 20 of his assistants; J. Bruce Ismay, president of the International Mercantile Marine Co. and chairman of the board and managing director of the Oceanic Steam Navigation Co., owners of the White Star Line. The night of the terrible accident, Jack was about to climb into bed when he felt the ship sway slightly. The ship's engines stopped and voices and running feet could be heard on deck. Jack called to his father that he was going up on deck to see the "fun." His father decided that he would dress and join him. Although no iceberg was visible they were informed that the ship had hit one. After some milling about on deck, Jack and his father came in from the cold. It was then that they met the designer Andrews, who predicted that he did not "give the ship much over an hour to live." Jack remarked, "No one is better qualified to know." At 13:15 a.m. the stewards passed the word for everyone to go below and dress in warm clothing and life preservers. Jack and his father went below to find his mother and her maid fully dressed. They hurried up to the lounge on "A" deck which was fast becoming crowded. Jack writes, "At 13.45 a.m. the noise on deck was terrific. the now idle boilers were blowing off excess steam through relief valves and the crew was launching distress rockets. Word was passed for women and children to board lifeboats 17 on the port side." The Thayer party proceeded to the port side of the ship. Jack and friend Milton Long were separated from the rest and they moved to the starboard side of the ship to collect themselves and decide what to do. At 1:45 a.m. the ship was down at the head and the bow covered with water. Jack and Milton watched as the last boats were loaded. It was a confusing scene and Jack decided against trying for a lifeboat. They witnessed only a few cowardly incidents and many heroic acts. The boats were leaving rapidly and the two young men discussed getting into one of the boats but the crowds were great. They stood by the empty davits of a lifeboat that had left. Here, close to the bridge they watched a star through the falls of the davit to measure the rate at which the ship was going down. Milton talked Jack out of trying to swim to a half-full lifeboat. It wasn't until later that Jack came to the full realization that the water temperature was 28 degrees and most deaths occurred from the freezing cold and not drowning. The stern lifeboats, four on the port and four on the starboard side had already left the ship. One of the first boats to leave carried only 12 people, Sir Cosmo and Lady Duff Gordon and 10 others. Most of the boats were loaded with 40 to 45, with the exception of the last few to go. And they were loaded to full capacity. The boats could hold over 60 people, but the officers were afraid to load them to capacity, fearing that they might have buckled or broken from the weight as they were suspended over the water from 60 feet above. As they stood there the only person Jack recognized nearby was Mr Lindley [?] whom he had also just met that evening. Another man Jack saw lurched by drinking from a bottle of Gordon’s gin, he said "If I ever get out of this there is one man I'll never see again" in fact Charles Joughin was one of the first survivors that Thayer did meet! As the ship sank deeper and more rapidly Jack thought about jumping for it as others appeared to be doing towards the stern, after all, he was a strong swimmer. However Long was not and persuaded Jack against it. Eventually, however, they could wait no more and after saying goodbye to each other they jumped up on the rail Discovering they were only 12 to 15 feet above the water. Long put his legs over and held on a minute and said 'You are coming, boy, aren't you?' Jack replied 'Go ahead, I'll be with you in a minute.' Long then slid down the side of the ship. Jack never saw him again as Milton was sucked onto a deck below and drowned . A short while later Jack jumped out, feet first. (Later, Jack would realize that his watch had stopped at 2:22 a.m.) He surfaced well clear of the ship. Jack was struggling and freezing in the water but rather than swim away immediately, he turned for a moment to watch the ship break up. He saw the second funnel break loose and fall into the water in front of him. Again he was sucked under the water. Later when pieces of the story were put together it was speculated that his father, who was last seen standing under the second funnel, had been struck and killed by it. When Jack surfaced again he found himself next to a collapsible lifeboat which was floating upside down. Already there were several men clinging to it. Jack was helped onto the boat and eventually there were 28 men hanging on for their lives before rescue came. Jack tells of that terrible night on the capsized lifeboat. They had to remain motionless, afraid they would fall into the icy water if they moved at all. Daylight came and they were finally allowed to untangle themselves from the huddled mass on the boat. With the aid of a whistle they were able to summon other lifeboats to come to their aid. Two lifeboats from the Titanic took the 28 men off their precarious perch and in doing so undoubtedly saved their lives. In his story, he recalls how the night was shattered for 20 or 30 minutes as those in the water cried for help until they could no longer withstand the cold and exposure. But the partially filled lifeboats standing by never came back to help. It is believed that the survivors were afraid that the boats would be swamped by the people in the water. Whatever the reason, it is hard to understand why they made no move to help. Jack writes, "How could any human-being fail to heed those cries?" He continues, "The most heartrending part of the whole tragedy was the failure, right after the Titanic sank, of those boats which were only partially loaded, to pick up the poor souls in the water. There they were, only 400 or 500 yards away, listening to the cries, and still they did not come back." When Jack and his companions were finally taken off the collapsible boat, and the two lifeboats came to the rescue, Jack's own mother was manning one of the oars. By 7:30 a.m., the Carpathia had arrived on the scene to rescue the survivors. Jack climbed aboard and there was his mother waiting at the top of the ladder. Their joyful reunion was short-lived when they realized that Jack's father had not been among those saved. Jack writes that he was give a cup of brandy, the first alcohol he had ever had in his life. After a nap he woke up feeling "fit and well, just as though nothing had happened." 18 When he learned that J. Bruce Ismay, the chairman of the Oceanic Steam Navigation Co., owners of the White Star Line and the Titanic, was on board he searched for him. He found Ismay seated, in his pajamas on a bunk, staring straight ahead, shaking like a leaf. "I am almost certain," he says, "that on the Titanic his hair had been black with slight tinges of gray, but now his hair was virtually snow white. I have never seen a man so completely wrecked. Nothing I could do or say brought any response." Jack, it appears, did follow the plan for his life but, certainly it was never the same after what happened that fateful night in 1912. After their arrival in New York, Jack, his mother and Miss Fleming took the Thayer's private train carriage from Jersey City, NJ back home to Haverford. Jack Thayer graduated from the University of Pennsylvania and went into banking; later he returned to the University as Financial Vice-President and Treasurer. He married Lois Cassatt and they had two sons. Edward C. Thayer and John B. Thayer IV. In 1940 Jack produced a pamphlet relating his experiences on the Titanic as an attempt, perhaps, to exorcise some of the memories that still haunted him. During the second world war both of Jack's sons joined the services. It is likely that the bout of depression that afflicted Jack following the death of his son Edward on active service in the pacific led directly to his death, by his own hand, in 1945. He was buried at the Church of the Redeemer Cemetery, Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania. Mrs. John M. Brown, described her experience on the Titanic as the "most harrowing and terrible that any living soul could undergo," and “ in contradiction to several other statements, Mrs. Brown declared that she saw no signs of panic or disorder on the Titanic and did not know until later that there had been shooting on board the vessel. "I was in my berth when the crash came," Mrs. Brown said, "and after the first shock when I knew instinctively that the vessel was sinking I was comparatively calm. I had hardly reached deck when an officer called to me to enter a lifeboat. I did so, and saw the huge liner split in half, with a pang almost as keen as if I had seen somebody die." Mrs. Brown said that John B. Thayer, Jr., after jumping from the deck of the liner, clad only in pajamas, swam through cakes of floating ice to a broken raft. He was picked up by the boat of which Mrs. Brown was an occupant. Mrs. Brown said that it was about two hours after the Titanic sank that their boat came within sight of an object bobbing up and down in the cakes of ice, about fifty yards away. Nearing, they made out the form of a boy clinging with one leg and both arms wrapped around the piece of wreckage. Young Thayer uttered feeble cries as they pulled alongside. The lad was pulled into the already crowded lifeboat exhausted. With a weak, faint smile, Mrs. Brown said, the lad collapsed. Women, who were not rowing or assisting in maneuvering the boat, by vigorous rubbing soon brought Thayer to consciousness and shared part of their scanty attire to keep him from dying from exposure. In the meantime the boat bobbed about on the waves like a top, frequently striking cakes of ice.