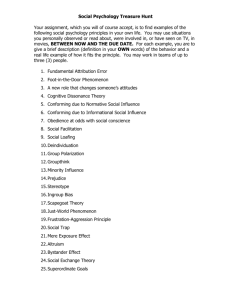

lecture slides

advertisement

Group Dynamics and Leadership Dr Lucia Garcia Lorenzo 9th November 2010 “…group mental life is essential to the full life of the individual... the satisfaction of this need has to be sought through membership of a group. Now ... in all [groups] ... the most prominent feeling ... the group experiences is the feeling of frustration – a very unpleasant surprise to the individual who comes seeking gratification.” (Bion, 1961/2010:54) Lecture Plan 0. What is a group? 1 Group dynamics 1.1. Interdependance: Facilitation and inhibition 1.2. Socio-cognitive processes: cohesiveness, socialisation. 1.3. Structure: norms, roles and status 1.4. Theoretical elaboration of groups 2 Who leads the group ? Leadership theories 2.1. The trait approach 2.2. Contingency approach 2.3. Styles of leadership 2.4. Transactional and transformational leadership 2.5. Post-Heroic Leadership 2.6. Culture, gender and leadership 1 What is agroup? • Interdependence of relationships among members • Group not static entity but in continuous transformation • Generates individual, interpersonal and collective process socio-cognitive processes • Develops a structure 1 What is a group? Johnson and Johnson (1987:8): “‘A group is: • two or more individuals in (face-to-face) interaction, • each aware of her membership in the group, • each aware of the others who belong to the group, and • each aware of their positive interdependence as they strive to achieve mutual goals” Small, (face-to-face), interactive, task-oriented groups, SP 1.1. Interdependence: Facilitation Effects of the audience Social Facilitation (Allport, 1920) People perform better on a task when other people are present (not competing) – so the mere presence of others can enhance performance Yet, only in simple tasks: on more complex tasks performance is impaired by the presence of other people Drive Theory (Zajonc, 1965): Social facilitation has two dimensions: • The arousing presence of others • Effects of task complexity 1.1. Interdependance: Facilitation Zajonc (1965): Performance of simple and complex tasks alone and in the presence of others 300 250 200 150 task performance 100 Hi = worse performance 50 0 Simple Alone Simple Other Complex Complex Alone Other 1.1. Interdependance: Facilitation The effects of the audience • Evaluation apprehension model. (Cottrell, 1972) • Distraction-conflict theory (Baron, 1986) • Self-awareness theory (Wicklund, 1975) • Etc. 1.1. Interdependance: Facilitation BUT when tasks need interaction and inter-individual coordination ? Steiner (1976): Task taxonomy. Three Determinants of Group Performance. Divisible or unitary: • E.g., tasks where a division of labour is reasonable (e.g., production lines) versus those where it is better for everyone to work together (e.g., tug of war) Maximising or optimising goal: • E.g., where the task job requires people to do as much as possible, (e.g., tug-of-war), or where a particular quantity is to be achieved (e.g., pulling a rope maintaining a specified fixed force) 1.1. Interdependance: Facilitation Steiner (1976) • How are individual’s efforts related to the total group output ? • Additive: group output is the sum of individual’s output (e.g., a group of people picking blackberries) • Compensatory: group output is the average of the individual outputs • Disjunctive: when the best individual performance is chosen suggestion as to which restaurant to dine in) (e.g., a • Conjunctive: the group’s performance is a function of the slowest member (e.g., an assembly line team) • Discretionary: no task features or social conventions but group free to decide on its course of action (e.g shovelling snow together) • Coordination loss 1.1. Interdependance: Inhibition Motivation Loss/Social Loafing (Williams, Karau & Bourgeois, 1993): Less individual effort when working on collective task Meta analysis of 78 studies SL apparent in 80% Social Loafing vs. Social Compensation (Karau and Williams, 1993) (Zaccaro, 1984) 1. Task nature: Irrelevant or trivial task SL Important or possible to add to the partial solutions SC 2. Significance of group to its members: • Members of ad hoc groups SL When participants identify with, value their group membership SC 3. Culture Individualistic cultures SL Collectivist cultures SC (Hofstede, 1980) 1.2. Socio-cognitive processes: Cohesiveness What transforms an aggregation of individuals into a group? Cohesiveness (esprit de corps, solidarity, team spirit) Field of forces • • • • (Festinger, Schachter and Back, 1950) Attractiveness of the group and its members Satisfaction of individual goals Behaviour • Membership continuity • adherence to group standards 1.2. Socio-cognitive processes: Cohesiveness FIELD OF FORCES BEHAVIOUR Attractiveness Membership Continuity • Of group • Of group members Cohesiveness Mediation of goals: • Social interaction per se • Individual goals needing interdependence Adherence to group standards 1.2. Socio-cognitive processes: Cohesiveness Hogg (1993) social identity vs individuals in group aggregation? Difference between: • • Inter-personal attraction Social attraction -the 'liking' component of group membership. Produced by self-categorisation (Turner et al 1987) ppart of the group processes that includes ethnocentrism, stereotyping, ingroup solidarity etc. 1.2. Socio-cognitive processes: Socialisation Groups are dynamic structures that continuously change over time. How groups develop (Tuckman, 1965, Gersick, 1989): 1. Forming 2. Conforming 3. Storming 4. Norming 5. Reforming 6. Performing 7. Adjourning 8. Mourning 1.2. Socio-cognitive processes: Socialisation Groups as dynamic structures that continuously change over time. Role Social Process Strategies Prospective member Full Member New member Marginal Member Ex-member Re-socialisation Remembrance Accommodation Assimilation Tradition Reminiscence Maintenance Investigation Socialisation Role negotiation Recruitment Reconnaissance Accommodation Assimilation Entry (Moreland and Levine, 1982) Acceptance Divergence Exit 1.3. Structure: norms 1.3. Structure: norms Shared beliefs about appropriate behaviour for all group members • Descriptive (is) and prescriptive (ought) • Explicit (norms enforced by law) and implicit (taken-for-granted) • Individually: Provide a frame of reference within which individual behaviour can be located (Sherif, 1936) • Group level: Coordinate the actions of group members to accomplish group goals • Provide stability and continuity therefore resistant to change. • Standard of group behaviour used in social influence processes. 1.3. Structure: roles 1.3. Structure: Roles Describe and prescribe behaviour of particular group members • Not people but behavioural prescriptions assigned to people • Implicit • Emerge to facilitate group functioning but inflexibility can be detrimental. • We tend to 'act or assume' roles • Influence who we are: identity and self-concept. (Haslam and Reicher, (group of friends), explicit (ICU team) (Zimbardo and Movahedi, 1975) simulated prison experiment 2005) 1.3. Structure: Roles (Belbin, 1981) Roles and descriptions Allowable weakness Plant: Creative, imaginative, unorthodox. Solves difficult problems. Ignores details. Too preoccupied to communicate effectively. Resource investigator: Extrovert, Overoptimistic. Loses interest once enthusiast, communicative. Explores initial enthusiasm has passed. opportunities. Develops contacts Coordinator: Mature, confident, a good chairperson. Delegates Can be seen as manipulative. Delegates personal work Shaper: challenging, dynamic, thrives on pressure. Has the drive and the courage to overcome obstacles. Can provoke others. Hurts people’s feelings. ETC. 1.3. Structure: Status Not all roles are equal • Highest status role is the LEADER • Properties of higher status roles • Commonly agreed prestige • Possibility of creativity and innovation adopted by the group. Able to break and/or extend norms • Status hierarchies can develop and vary over time and situation despite tendency to institutionalisation. • Status hierarchies emerge readily in new groups categorisation theory, 1954) (Festinger's social 1.4. Theoretical elaboration of groups Interdependence (Lewin, 1947) : • More than just sum of members interactions • Co-construction of meaning among group members sharing a particular experience. • Group develops structure with positions and shared aims • What happens to a member affects the group • Goals achieved through members interaction • Satisfaction of affiliation, reality management and instrumental needs • Through interaction a stable pattern of relationships is established organizing social relations (norms, status and values) 1.4. Theoretical elaboration of groups Socio-cognitive processes • The group perceives itself/is perceived by others as a totality. • Group awareness: 'us', 'group mentality' (Bion) • Beyond pertence Group as reference: individual actively engages in formulating social norms and values that shape thought and action. • Creation of endo-groups (positive relationship) and exogroups (negative relationship). • Minimal Group Paradigm, SIT, Social Categorization 1.4. Theoretical elaboration of groups Structure • Regularities that emerge among group members • Orders and controls conflicts and tensions • Influences individuals behaviour and members' social positions in the group • Regulates interactions, communication, efficiency, roles, status and norms. • Roles: Shape expected behaviours and needed tasks for the group to function • Status: Provides information regarding members behaviour and individuals' position in the group 2. Leadership: Does it matter who is in charge? It Does Matter WHO is in charge • Social and organizational hierarchies do contain real power differences: “power over” and “power to” • The costs of misapplication of power might include: Injury, Death, financial loss, Stress • Leadership quality determines the performance of the group • Poor group performance may therefore potentially be overcome by changing the leadership 2. Leadership: Does it matter who is in charge? It Doesn’t Matter WHO is in Charge • No real power (Chester Barnard, 1938) • There are few real differences between leaders and followers – so anyone could be a leader (Mann, 1961) • It all depends on the context – “contingency theories” (Fiedler, 1964) • Group performance is largely determined by factors that are beyond the power of the leader to influence (Pfeffer, 1978) 2.1. Leadership: The trait approach. The “Great Person” Theory Effective leadership is based on individual personality characteristics – in the past, often thought to be innate (“born leaders”); more recently such qualities assumed to be acquired • Popular theory: • • • it offers ways to measure the strength of leadership qualities and so to evaluate candidates for leadership positions it reflects much of our thinking regarding the world – using person attributions regarding political and historical events (e.g., locating the causes of the war in Iraq) 2.1. Leadership: The trait approach. Common Leader Traits Kirkpatrick and Locke (1991): • • • • • • • • Drive Leadership motivation Honesty and integrity Self-confidence/self-esteem/dominance Extraversion Cognitive ability/intelligence/problem solving Knowledge of the business Conservatism 2.1. Leadership: The trait approach. From ‘great person’ to ‘strong men’ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8xRaUqgWPN0&fe ature=PlayList&p=D83AA0216AD6F393&playnex t=1&playnext_from=PL&index=1 2.1. Leadership: The trait approach. Little evidence of there being consistent and specific personality traits possessed by all leaders Most of the evidence is from ad hoc groups’ ratings of leadership Not clear the same kinds of people become leaders in real organisations Or that they will make good leaders Evidence from Real World Groups (Emler, Tarry and Soat; 1998) Rating qualities of actual leaders in real groups, those who had frequent contacts with leaders indicated • Moral responsibility, • Honesty, • Extraversion, • Self-esteem as most important 2.2. Leadership: The contingency approaches. Given relatively few characteristics are common across leaders, focus on context as a major variable in leadership Contingency Theory of leadership (Fiedler, 1967): – Leadership style develops from a person’s personality, and leads to one of two styles of leadership: • Task-focused leadership • Person-focused leadership – Leaders were asked to describe their co-workers on various dimensions, thus arriving at a description of their “least preferred co-worker” (LPC): • • If LPC described negatively, then leader task focused If LPC described positively, then leader person focused 2.2. Leadership: The contingency approaches. The appropriateness of a person-focused or a task-focused leader depends on the situation: • leader-group relations (the extent to which the leader has support) • task structure (well specified or unclear) • leader’s power (the extent to which they control rewards and punishments) Over-all: • Task-focused leadership works better when conditions are very favourable (positive leader-group relations, clear task, high authority) or very unfavourable (poor leader-group relations, unclear task, low authority) • In all other conditions, a person-centred style may get best results 2.2. Leadership: The contingency approaches. • • Fiedler’s view has some empirical support – matching leader needed to the situation and task also makes intuitive sense However: • the view has been controversial (e.g., the assumption that leaders cannot vary their style of leadership to suit the situation because style is fixed by personality) • Static: Fail to capture the 'dance' between leaders and followers 2.3. Leadership: Leadership styles Lewin, Lippit & White (1939): Assessed styles of leadership over 7 weeks in an afterschool club for 11 year-old boys Autocratic: • • More aggression, greater dependence on leader, more control. Worked hardest, but only when leader present Democratic: • • Friendlier atmosphere, group-centred, reasonably task-oriented. Leader absence made no difference to work rate Laissez-faire: • • Leaders faced considerable demands for information. Spent more time playing than working. Worked harder when leader absent 2.4. Leadership: Transactional and transformational leaders Transactional Leaders (Statt, 2004): • Leadership as a process of exchange • Task-focused: operate a system of contingent rewards • Management by exception: no attempt to change subordinates’ working methods as long as the performance goals are met •Transformational Leaders (Burns, 1978): • • • • Individualised consideration Intellectual stimulation Charismatic/inspirational motivation The aim is to achieve: • motivation and performance above and beyond the call of duty • willingly given • without apparent expectation of additional economic reward 2.5. Leadership: Post-heroic leadership Bradford and Cohen (1984); (Heifetz and Laurie, 1997): 1990’s/2000’s: associated with transformational leadership but focus on managers developing their subordinates. “Manager as developer”: • • • Shared responsibility with employees Empowerment of employees: sharing the power around as a “captain of industry” Developing constant opportunities to learn – “the learning organisation” Key factors in development of Post-Heroic Leadership: • • • Rapidly changing business environment: leadership as ensuring that the organisation adapts successfully Discontent with the image of managers (Enron, Northern Rock, etc) Managers and diversity 2.5. Leadership: Post-heroic leadership http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IrCeVwwu0Xcfeature =related 2.6. Leadership: Culture and leadership Cultural differences in both the definition of leadership and in specific leadership behaviours according with broad differences between collectivist (Eastern Asian) and individualistic (Western) cultures Leadership: • Individualistic cultures: Leader is expected to have vision, authority and be a decision-maker • Collectivist cultures: Leader is expected to combine being participative, supportive and nurturing with being decisive Leadership roles: • Individualistic cultures: Leader’s role is largely confined to overseeing the subordinates’ activities whilst in the workplace • Collectivist cultures: Leader may have a wider role, being concerned with subordinates’ private lives and well-being outside the workplace 2.6. Leadership: Gender and leadership Gender differences regarding leadership tendencies, and their assessed effectiveness Eagly, Karu,Makhijani (1995): group behaviour in informal groups •Females: tend to be more democratic, person-focused leaders •Males : tend to be more autocratic, task-focused leaders Meta-analysis re. Effectiveness Overall – no difference in evidence regarding perceived effectiveness But differences re. of gender-stereotyped appropriateness of role: Men more effective when role defined in task terms Women more when defined in interpersonal ability terms •Different effects of organisational level: • Men are more effective in first-level (line-management) positions Women more effective in 2nd level (middle-management) positions 2.7. Current trends on leadership research • More holistic view of leadership e.g. including followers, the context, the levels, dynamics etc • Examining how the 'process' of leadership actually takes place (e.g. how the leader and followers process information and how they affect each other, the group and organization in doing so) • Deriving alternatives to examine leadership (e.g. mixed methods of research) • Some further/unresolved questions: • Are leaders born or made? • How do followers affect successful leaders? • Why some charismatic leaders generate and others destroy? • What is the impact of technology in leadership? Some further references Johnson, D.W. and Johnson, F.P. (1987) Joining together: Group theory and group skills. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Bion, W.R. (1961/2010) Experiences in groups. London: Routledge. Freud, S. (1921/2009) Group psychology and the analysis of the ego. W.W. Norton and Co: London Allport, F.H. (1920) The influence of the group upon association and thought. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 3 159-182. Zajonc, R.B. (1965) Social facilitation. Science, 19, 269-279. Cottrell, N. B. (1972) Social facilitation. In C. McClintock (Ed) Experimental social psychology (185-236) New York: Holt, Rinehart and Wilson. Baron, R.S. (1986) Distraction-conflict theory: Progress and problems. In L. Berkowitz (Ed) Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 20:1-40) New York: Academic Press. Wicklund, R.A. (1975) Objective self-awareness. In: In L. Berkowitz (Ed) Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 8:233-275) New York: Academic Press. Steiner, I.D. (1976) Task-performing groups. In J.W. Thibaut and J. T. Spence (Eds.) Contemporary topics in social psychology. (pp:393-422) NJ: General learning press. Williams, K.D. Karau, S.J. And Bourgeois, M. (1993): working on collective tasks: Social loafing and social compensation. In: M.A. Hogg and Abrams, D. (eds.) Group motivation: Social Psychological perspectives (130148) London: Harvester Wheatsheaf. Karau, S.J. and Williams, K.D. (1993) Social loafing: A meta-analytical review and theoretical investigation Journal of personality and social psychology, 65, 681-706. Zaccaro, S.J. (1984) Social loafing: The role of task attractiveness. Personality and social Psychology bulletin, 10 99-106. Festinger,L. Schachter, S. and Back, K. (1950) Social pressures in informal groups : a study of human factors in housing . New York: Harper. Hofstede, G. (1980) Culture's consequences: International differences in work related values. Beverly hills, CA: Sage. Hogg, M.A and Vaughan, G.M. (2008) Social Psychology. London: Prentice Hall. Hogg, M. A. (1993) Group cohesiveness: A critical review and some new directions. European review of social psychology. 4, 85-111. Turner, J.C, Hogg, M.A. Oakes, P.J. Reicher, S.D. And Weatherell, M . S. (1987) Rediscovering the social group: A self- categorisation theory. Oxford: Blackwell. Tuckman, B.W. (1965) developmental sequence in small groups. Psychological bulletin, 63, 3840399. Moreland, RL. And Levine, JM (1982) Socialisation in small groups: Temporal chnages in individual-group relations, In L. Berkowitz (Ed) Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 15:137192) New York: Academic Press. Lewin, K. (1947) Group decision and social change. In T.M. Newcomb and E.L. Harley (Eds.) Readings in Social Psychology. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. Sherif, M. and Sherif, C.W. (1964) Reference groups. New York: Harper and Row. Tajfel, H. (1978) Social categorization, social identity, and social comparisons . In Tajfel, H. (Ed.) Differentiation between social groups. London: Academic Press. Brown, R. (2000) Group Processes. Oxford: Blackwell Pub.