UNIT 2-final- Demand and SUPPLY-to-print

advertisement

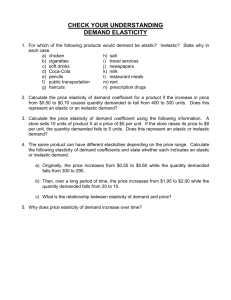

UNIT 2 - DEMAND AND SUPPLY ANALYSIS Introduction: The success of any business largely depends on sales and sales depend on market demand behaviour. Market demand analysis is one of the crucial requirements for the existence of any business enterprise. Analysis for the market demand is necessary. 2.1 Definition of Demand Demand (D) is a schedule that shows the various amounts of product consumers are willing and able to buy at each specific price in a series of possible prices during a specified time period. Demand = Desire to acquire it + willingness to pay for it + ability to pay for it. Quantity demanded (Qd) is the amount of a good or service that individuals are willing and able to buy at a particular price at a particular time. Demand is the quantity demanded at all prices during a specific time period. A change in price will change the quantity demanded, not the demand. Any other factors other than price change will change the demand. Non-price factors include income, preferences, expectation, number of buyers, etc. Law of Demand • Law of demand states: As price of goods increases, the quantity demanded of the good falls, and as the price of goods decreases, the quantity demanded of the good rises, ceteris paribus. Restated: there is an inverse relationship between price (P) and quantity demanded (Qd), other things remaining constant. Explanation of Law of Demand 1. Substitution Effect: As the price of product A increases, product A is comparatively more expensive than product B when B's price remain constant. Therefore, consumers will substitute B for A, causing the consumption of A to decrease. 2. Income Effect: Higher price will lower the consumption or purchase power of your income of the consumer and decrease the quantity demanded. Types of Demand 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Demand for consumer’s goods and producer’s goods Demand for perishable goods and durable goods Derived demand and autonomous demand Firm’s demand and industry demand Demands by total market and by market segments 1. Demand for consumer’s goods and producer’s goods (Direct demand and Derived demand): Consumer’s good are the ones used for final consumption by the consumers themselves. Some examples of consumer’s goods are food grains, televisions, shirts 1 etc. Producer’s goods are those which are used for the production of other goods such as the consumer’s good or even the producer’s goods. These include the raw materials used in the production process of any goods. The demand for the consumer’s goods is termed as direct demand because these goods are used directly for final consumption. For example, when a car owner buys a tyre for his cars, it is a consumable good. The demand for the producer’s goods is termed as derived demand because these goods are not used for final consumption but for the production of other goods. For example, when the tyre is bought by a car manufacturer to be used in the manufacturing process, or the retailer buying a tyre for reselling it is a producer good. 2. Demand for perishable goods and durable (non perishable) goods: Perishable goods are those which can be consumed only once and these goods themselves are consumed. Some examples are fruits, vegetables, food products, tooth paste, soaps etc. Durable goods are those which can be used more than once over a period of time and these goods themselves are not consumed while only the services which they offer to consumer or producer is consumed. For example in the consumer goods category, chair and television are durable goods. Similarly factory buildings, machinery etc are some of the examples of durable producer’s goods. This distinction is useful because the demand for durable and non durable products differ. The durable products present more complicated problems for demand analysis than non durable goods. Sales of non durable products are made largely to meet the current demand, which depends on the current conditions. Sales of durables occur only periodically and add to the stock of existing goods, whose services are consumed over a period of time. Durable goods have two kinds of demand based on their usage. One is the replacement of old products and the other is the new purchase which leads to expansion of total stock. Their demands fluctuate with business conditions. 3. Derived demand and autonomous demand: Derived demand is the demand for a product when its demand is tied to the purchase of some parent product. For example cement, brick and steel rods have derived demand since they are not needed for their own sake but for satisfying the demand for buildings. Autonomous demand is the demand for a product solely based on the utility of the product only. Its demand does not depend on any other product’s demand. Eg: demand for subject book. 4. Firm’s demand and industry demand: A firm’s demand or company’s demand is the demand for the products / services produced by a particular firm. Industry demand is the demand for the product of a particular industry. Demand for office furniture by customers which are produced by Godrej is a firm’s demand while demand for all office furniture manufacturers in India is the industry demand of office furniture in India. 5. Demands by total market and by market segments: The total market demand refers to the total demand for a product whereas the demand by market segment refers to the demands arising from different segments of the market. 2 A firm or an industry may be interested not only in the total demand for its products but also will be interested in the demand for its products arising from different market segments like the different regions, different uses for its product, different distribution channel etc. As it will be seen in price discrimination, each of these segments will differ significantly with respect to prices, net profit margins, competition, cyclical sensitivity and seasonal patterns. When these differences are significant and bigger, demand analysis should be confined to the individual market segments. A knowledge of these segment’s demand help a firm in manipulating the segments / market total demand. The concept of Demand Function What will be the factors that determine the demand for a commodity? In the case of consumption, the willingness to buy a commodity, that is the demand for that, depends on the factors such as: i) The income of the consumer ii) The price of the commodity iii) Prices of other goods and services on which the consumer spends his income iv) Tastes and preferences of the consumer, size of his family, social customs, expectations and advertisement, etc. Similarly, the case of a firm or producer the input demand for commodity depends on the factors like. i) ii) iii) iv) The total outlay or expenditure of the firm The price of that commodity Prices of other substitute and complementary inputs. The nature of technology etc. For the sake of simplicity let us concentrate on consumer demand for a commodity. Demand function Demand of a product depends on many factors like the price of the product, customer’s income, price of competition, prices of substitutes etc. A demand function states the dependence relationship between the demand for a product or service and the factors or variables affecting it. This relationship can be symbolically represented as: Dx= f(Px,Ps,Pc,I,Y,T,A,U) Where Dx is the demand for product x Px is the price of that product x Ps is the price of substitutes for x Pc is the price of complements of x I is the customer’s income Y is the level of household income T is the customer’s taste and preference A is the effect of advertising U denotes other determinants of demand for x 3 A consumer’s demand function for a commodity specifies the relationship between quantity of the commodity that he is willing to buy, and its demand factors. In other words, in a demand function, the quantity demanded is expressed as a function of the demand factors for the commodity. In mathematical form we can express the demand function for a commodity as: Qx = Dx (Px Ps Pc Y T) ....... (1) Where Qs is quantity of commodity X demanded, Px is the price of the commodity, Ps denotes the price of other commodity which can be substituted for X, Pc is the price of a commodity which is a complement of commodity X, Y is income of the consumer and T represents other demand factors such as tastes, preference, social customs etc., and D indicates the functional form of the relationship. There may be more than one substitute and / or complementary goods for commodity X. In this situation the specification of the demand function of commodity X can be expanded by including their prices. The demand function (1) may be linear or non-linear in shape. If it is linear then it can be expresses as: qx = ao + ax Px + as Ps + ac Pc + b Y + c T ......(2) Where a0 is a constant and ax, as, ac, b, c are also constant parameters called “marginal coefficients”. These are nothing but values of partial derivatives of the function. The interpretation of these coefficients is straight forward. If P increases by one unit, the quantity demanded Q will then change by ‘ax’ units, other variables remaining unchanged. Similar interpretation can be given for other coefficients in qx = ao + axPx + asPs + acPc + bY + cT . Some of these coefficients may be negative like ax and some positive like as. If the function is non-linear in shape it implies changing marginal coefficients with the levels of the concerned demand factor. For example the coefficient or Ps, may increase or decrease on increasing Px. One standard non-linear shape of the consumer demand function is exponential shown as: Qx = A Pxax Psas Pcac Yb Tc Where ax, as, ac, b, c are constant parameters (these are elasticity coefficients). Some of these parameters may be negative and some positive depending on how the quantity demanded responds to its determinants. We cannot find the shape of the demand function a priority. It is to be determined only on estimating or fitting the demand function a) The Relationship between Q and P It is a common observation that for most of the commodities the willingness to buy decreases as price of the commodity increases. Exceptions are everywhere for certain very essential goods like medicines; however, there may not be inverse relationship between quantity demanded and price. It may be straight like showing fixed quantity of the commodity that the consumer is willing to buy at different prices. Let us concentrate on the normal case of inverse relationship between price and quantity demanded of a commodity. If we plot the relationship using price and y-axis and quantity on x-axis, the graph would be seen as follows. 4 Price (per unit) A Sample Demand Curve PA 0 A QA Quantity demanded(per unit of time) It shows the relationship between the price of that commodity and the quantity that a consumer is willing to buy. It is called “demand curve” for the commodity. It is a convention in economics to take quantity on x-axis and price on y-axis while drawing a demand curve as shown above. This is for the sake of convenience of representing demand and other curves together to understand the process of price determination. The demand curve for a commodity is drawn on the assumption that other factors of demand remain unchanged. It is normally a downward slopping curve. In the form of a law we can state the relationship as following. The Law of Demand – Other things being equal, the quantity demanded of a commodity varies inversely with its price. Why a consumer buys more of commodity when its price decreases and less when the price increases? Possible explanations given for this at this stage are: i) When price declines the consumers saves one expenditure which brings him/her more of that commodity. We may call this as “Income effect”. ii) A consumer can substitute that commodity, when its price declines and other prices remaining constant, for some other commodity; this is called “Substitution effect”. iii) There is a third explanation of declining marginal utility as quantity increases. b) The relationship between quantity demand of a commodity and prices of other commodities. A fall in price on one-commodity may lower the consumer’s demand for other commodity or may raise it or leave it unchanged. Those are only three possibilities. Let us take two commodities case, S and X. If prices of say S commodity (Ps) increases then demand for X commodity goes up. This is possible when these two commodities are substitute for each other, ie.., they are used to satisfy same need separately. For example tea and coffee satisfy the need to drink. Why this happens? The answer is simple. An increase in price of S other things being constant, reduces the quantity demanded for S and increases the quantity demanded for X. The reverse of this will also be true. Consider another set of commodities C and X. If price of commodity C increases, other things being constant, the quantity demanded of C declines and also the quantity demanded of X declines and if the price of C declines then the quantity demanded of C increases but the quantity demanded of X may increase or remain unchanged. This is possible when these two goods are complementary goods i.e. they are used jointly to satisfy same need of the consumer. For example Fountain pen and Ink. 5 The third situation concerns with the neutral or unrelated goods. In an increase or decrease in price of one commodity has no effects on quantity demanded of other commodities then they are neutral or unrelated goods. The prices of other goods and services will not appear in the demand function as determinations for such commodities. c) The Relationship between Quantity Demanded and Income There are three possibilities for this type of relationship. An increase (decrease) in income of the consumer increases (decreases) the demand for the commodity. The commodities for which we get this type of positive relationship are called “normal” goods. For certain commodities like foodstuff, a rise in income causes an increase in quantity demanded in the initial stage but after a certain level of the consumer’s income the quantity demanded becomes invariable with respect to the income i.e. it remains at constant level. So they are having a positive relationship up to a level of income. For some goods, an increase in income of the consumer decreases the demand for the commodity. The commodities for which we get this type of positive relationship are called “inferior” goods or “Giffen” goods. There is a simple generalization of the relationship between consumption of goods and income for a consumer. This is known as Engel’s Law. According to this law, as income increases the proportion of income spent on food declines and the proportion spent on comforts and luxuries increase. This law is quite valid as we see form our own experience as consumers. d) Tastes and Preferences, Social Customs and Demand These are quite important factors of demand for different commodities. If the tastes and preference of consumers are in favour of a commodity then its demand will increase otherwise not. Social customs are also positive factors of demand for a large number of commodities. Some examples showing the relevance of all such factors for demands are as follows: i) There is less demand for wheat in South India as there is no preference for bread in this part of the country ii) People prefer different brands of same commodity because their tastes differ iii) Some students prefer to write by ball-point-pen and some by fountain-pen iv) Ladies buy “sindoor” in India since it is social custom to use it on the forehead by Indian ladies. v) Sweets are offered to “Gods” in temple in India because of social and religious customs. Advertisement and other kinds of sales promotion activities are used by business units to induce consumers preference or tastes in favour of the commodities and hence an increase in their demand. From this point of view, such activities are treated as additional demand factors. e) Expectations and other Factors If prices and income are expected to increase, the quantity demanded for certain commodities may go up. In the situation of rising prices, consumers generally buy more and stock the commodities for future consumption. If the prices are expected to fall, they may not buy more 6 or postpone certain type of consumption for future. Apart from expectations there might be some other seasonal or temporary factors affecting the demand for a commodity in some way or other. Similarly, if income is expected to rise then a consumer may buy more of a commodity since he would be able to pay for this later on. Elasticity of Demand In economics, the demand elasticity refers to how sensitive the demand for a good is to changes in other economic variables. Demand elasticity is important because it helps firms model the potential change in demand due to changes in price of the good, the effect of changes in prices of other goods and many other important market factors. A firm grasp of demand elasticity helps to guide firms toward more optimal competitive behavior. Elasticities greater than one are called "elastic," elasticities less than one are "inelastic," and elasticities equal to one are "unit elastic."' Price Elasticity Of Demand It is a measure of the relationship between a change in the quantity demanded of a particular good and a change in its price. Price elasticity of demand is a term in economics often used when discussing price sensitivity. If a small change in price is accompanied by a large change in quantity demanded, the product is said to be elastic (or responsive to price changes). Conversely, a product is inelastic if a large change in price is accompanied by a small amount of change in quantity demanded. Businesses evaluate price elasticity of demand for various products to help predict the impact of a pricing on product sales. Typically, businesses charge higher prices if demand for the product is price inelastic. Price elasticity of demand=% change in demand / % change in price(negative change) Perfectly elastic = 90% / 0% Relatively elastic = 20% / 10% (it is >1) Unit elasticity = 10% / 10% Relatively inelastic = 5% / 10% (it is <1) Perfectly inelastic = 0% / 10% Income elasticity of demand= % change in demand / % change in income (positive) Cross elasticity of demand=% change in demand of product ‘x’ / % change in price of product ‘y’ (positive for substitutes; negative for complements and zero for unrelated goods) Advertising elasticity of demand= % change in sales / % change in advertisement expenditure (positive) Production elasticity of demand=% change in output / % change in inputs (positive) Factors influencing elasticity – Types of product, Availability of substitutes etc. 7 Essential goods –salt, sugar, rice-inelastic Necessaries – cigarette, wine,- less PRICE elastic Luxuries – plasma TV, car,- elastic Substitutes – tea/coffee, parota /chapathi- elastic Alternative uses – coal, electricity- elastic Durables – watch, shoes, bike- elastic Uses / Applications Tax can be raised for products with inelastic demand Monopolist (only one seller for a product) – raise prices of inelastic goods & reduce prices of elastic goods Demand Forecasting Demand for a particular product results in the sales of that product and constitutes the primary source of revenue for business. One important reason to predict the future demand and sales is that the organization can produce the adequate amount of products to satisfy this demand. This is because production of goods constitutes a huge cost for the organization and the money is locked if goods are unsold. If the demand is high and there is no adequate number of products available in the market, then the revenue which would have come from this demand is lost and moreover customers get frustrated due to the non availability of products. Thus forecasting demand becomes important for an organization. The more realistic the forecasts are, the more effective the decisions made by managers will be. Forecasting demand is an important task for just about any type of business. Accurately projecting the demand for specific goods and services helps companies to order raw materials and schedule production of those products in a timely manner, making it possible to fill consumer orders quickly and efficiently without the need to build up a large inventory. While the process may vary in detail from one setting to another, there are a few basic steps that can make demand forecasting a much simpler process. Purpose of forecasting demand Taking the time frame into consideration there are two types of forecasting 1. Short-run forecast 2. Long-run forecast The purpose of these forecasts however differs, In short-run forecasts, the prime focus is on the seasonal patterns. Such forecasts help in preparing suitable sales policies and proper scheduling of output to avoid over stocking or delays in meeting the orders, both of these are costly. Besides giving an idea about the most likely demand, short-run forecasts also help in arriving at suitable price for the product and in deciding about the necessary adjustments in the promotional activities such as advertising and sales promotion. Long-run forecasts help in proper capital planning. Taking into consideration the demand for a product over a long period of time, managers plan to invest the capital in new machinery, recruit new manpower etc. If there is an increase in demand in short-run, managers may not be able to invest huge amounts of money in new machinery, building etc because this short 8 term demand will vane. But if managers find that there is going to be a sustained and substantial increase in demand for a long period of time, and then they can invest on capital equipment (machinery, building). This long term forecasting helps in saving the wastages in materials, man hours, machine time and capacity. In long-run forecasting, changes in variables like population, age group patterns, consumption patterns etc are included. Steps involved in forecasting: The following are the necessary steps which will ensure a good forecast: 1. Identify and clearly state the objectives of forecasting-short term or long term, market or industry as a whole etc. 2. Select appropriate methods for forecasting. The selection of an appropriate method for forecasting depends on the objectives of forecasting. Different objectives will use different tools. 3. Identify the variable affecting the demand for the product and express them in appropriate form. 4. Gather the relevant data to represent the variables. 5. Determine the most probable relationship between the dependent variable and the independent variable through the use of statistical techniques. 6. Prepare the forecast and interpret the results. Interpretation of the analysis of the data is usually done by the management Basic Steps: Identify the products that are to be considered as part of the forecast process. Doing so helps to create a sense of focus for the effort and make it easier to gauge the public's recognition and attraction to those products, rather than simply relying on the overall reaction of consumers to the brand name or the overall product line. Set parameters for the demand forecast. Establish a specific time frame for the projection, such as the beginning of the second quarter to the end of that same quarter in the upcoming business year. This makes it easier to include events that are highly likely to occur in that time frame and have some effect on consumer demand for the product under consideration Determine the target market or markets for the product. The market may be composed of demographics that have to do with age, gender, location or any other set of identifying characteristics desired. This can also add focus to the demand forecast since it helps the business to understand the level of business volume that can be reasonably anticipated from that demographic variable. Gather data relevant to the effort to forecast demand. Information such as a breakdown in population within targeted areas, dividing by age groups or economic classes, can often help make it easier to determine the approximate number of sales to anticipate during the period under consideration. Calculate the actual forecast. While there are several different formulas used for this process, most will require assuming that a fixed percentage of the target market will consume the product a certain number of times during the forecast period. Typically, those percentages are based on either industry standards relevant to the product or the actual history of past periods associated with the actual good or service offered by the business. Tips: Depending on the broadness of the product's appeal, it may be necessary to create a series of forecasts that have to do with several different demographics. For example, if the product regularly generates sales among both single and married females, a more precise projection can be managed by approaching each calculation separately, rather than simply creating a general forecast. 9 The results of forecasting demand can make it easier to determine the structure of marketing plans, including when and how to use different types of advertising mediums. Depending on the response from different segments of the consumer market, a company may find that more advertising via radio and online would be a better use of advertising funds than print ads and television. The Importance of Demand Forecasting Forecasting product demand is crucial to any supplier, manufacturer, or retailer. Forecasts of future demand will determine the quantities that should be purchased, produced, and shipped. Demand forecasts are necessary since the basic operations process, moving from the suppliers' raw materials to finished goods in the customers' hands, takes time. Most firms cannot simply wait for demand to emerge and then react to it. Instead, they must anticipate and plan for future demand so that they can react immediately to customer orders as they occur. In general practice, accurate demand forecasts lead to efficient operations and high levels of customer service, while inaccurate forecasts will inevitably lead to inefficient, high cost operations and/or poor levels of customer service. Seasonal Fluctuations Every business sees seasonal fluctuations. Holidays and weather changes influence products and services that consumers want. While it is extremely important to account for how seasonal changes affect demand, it may be possible to benefit further from this. Understanding how seasonal factors affect consumers helps businesses position themselves to take advantage. General Approaches to Demand Forecasting All firms forecast demand, but it would be difficult to find any two firms that forecast demand in exactly the same way. Over the last few decades, many different forecasting techniques have been developed in a number of different application areas, including engineering and economics. Many such procedures have been applied to the practical problem of forecasting demand in a logistics system, with varying degrees of success. Most commercial software packages that support demand forecasting in a logistics system include dozens of different forecasting algorithms that the analyst can use to generate alternative demand forecasts. While scores of different forecasting techniques exist, almost any forecasting procedure can be broadly classified into one of the following four basic categories based on the fundamental approach towards the forecasting problem that is employed by the technique. 1. Judgmental Approaches. The essence of the judgmental approach is to address the forecasting issue by assuming that someone else knows and can tell you the right answer. That is, in a judgment-based technique we gather the knowledge and opinions of people who are in a position to know what demand will be. For example, we might conduct a survey of the customer base to estimate what our sales will be next month. 2. Experimental Approaches. Another approach to demand forecasting, which is appealing when an item is "new" and when there is no other information upon which to base a forecast, is to conduct a demand experiment on a small group of customers and to extrapolate the results to a larger population. For example, firms will often test a new consumer product in a geographically isolated "test market" to establish its probable market share. This experience is then extrapolated to the national market to plan the new product launch. Experimental 10 approaches are very useful and necessary for new products, but for existing products that have an accumulated historical demand record, it seems intuitive that demand forecasts should somehow be based on this demand experience. 3. Relational/Causal Approaches. The assumption behind a causal or relational forecast is that, simply put, there is a reason why people buy our product. If we can understand what that reason (or set of reasons) is, we can use that understanding to develop a demand forecast. For example, if we sell umbrellas at a sidewalk stand, we would probably notice that daily demand is strongly correlated to the weather – we sell more umbrellas when it rains. Once we have established this relationship, a good weather forecast will help us order enough umbrellas to meet the expected demand. 4. "Time Series" Approaches. A time series procedure is fundamentally different than the first three approaches we have discussed. In a pure time series technique, no judgment or expertise or opinion is sought. We do not look for "causes" or relationships or factors which somehow "drive" demand. We do not test items or experiment with customers. By their nature, time series procedures are applied to demand data that are longitudinal rather than cross-sectional. That is, the demand data represent experience that is repeated over time rather than across items or locations. The essence of the approach is to recognize (or assume) that demand occurs over time in patterns that repeat themselves, at least approximately. If we can describe these general patterns or tendencies, without regard to their "causes", we can use this description to form the basis of a forecast. Comment on all four approaches: In one sense, all forecasting procedures involve the analysis of historical experience into patterns and the projection of those patterns into the future in the belief that the future will somehow resemble the past. The differences in the four approaches are in the way this "search for pattern" is conducted. Judgmental approaches rely on the subjective, ad-hoc analyses of external individuals. Experimental tools extrapolate results from small numbers of customers to large populations. Causal methods search for reasons for demand. Time series techniques simply analyze the demand data themselves to identify temporal patterns that emerge and persist. Forecasting methods/techniques There are two types of techniques in forecasting the demand – namely Qualitative and Quantitative. Qualitative techniques are Consumer Survey methods, Sales force opinion method, Expert opinion method and Market Experiments. Under Consumer Survey methods, we can have (i) Complete enumeration survey method, (ii) Sample survey method, and (iii) End-use method. Under Market Experiments, we do (i) Experimentation in laboratory, and (ii) Test marketing. Quantitative techniques are Mechanical Exploration or Trend Projection, Barometric techniques, Statistical methods, Econometric method, and Simultaneous Equations method. Under Mechanical Exploration or Trend Projection we can do (i) Fitting trend line by observation, (ii) Time series analysis employing least squares method (linear and non-linear), (iii) Forecasting by decomposing a time series, (iv)Smoothening methods namely Moving averages and exponential smoothening, and (v) ARIMA method. Under Statistical methods, we have (i) Naïve Models and (ii) Correlation and Regression method. Demand for New Items 11 New product introductions present a special problem in that there is no historical time series available for estimating a model. At issue, is not only the estimation of the sales at every future period but also, for example, estimates of the time it takes to reach certain sales volumes. In this and other contexts where there is no reliable historical time series or when there are reasons to believe that future patterns will be very different from historical ones, qualitative methods and judgment are used. Unfortunately, many market research procedures, which are based on questionnaires and interviews of potential customers, notoriously over-estimate the demand since most respondents have no stake in the outcome. Data can also be collected from marketing and sales personnel, who are in touch with customers and can have an intuition regarding the demand for some products. Other sources of informed opinions are channel partners, such as distributors, retailers, and direct sales organizations. New Analytical ToolsA wide variety of analysis tools can be used to model consumer demand - from traditional statistical approaches to neural networks and data mining. Using these demand models enables estimation of future demand: forecasting. Possibly, a combination of multiple types of modeling tools may lead to the best forecasts. Supply The supply of a product means “the amount of that product which producers are able and willing to offer for sale at a given price”. Individuals control the factors of production – inputs, or resources, necessary to produce goods. Individuals supply factors of production to firms. The analysis of the supply of produced goods has two parts: An analysis of the supply of the factors of production by households and an analysis of why firms transform those factors of production into usable goods and services. When the price is low, manufacturers will produce less and supply fewer products to the market because the profit per unit of product sold is less. When the price is high, demand is less but the supply is high because of profit per unit of product sold is high. In both cases (demand and supply) the price of the product is the independent variable and the demand or supply is the dependent variable i.e. the demand or supply depends on the price, when other factors are constant. Thus when there is a change in price, the demand for the product by the customer or the supply of the product by manufacturers to the market changes. These two seemingly opposite happenings go on and on till equilibrium is reached where the price of product is both affordable by the consumers as well as profitable for the manufacturer called the market equilibrium. Supply Function A supply function represents how much of a good or service a producer/supplier will supply at a price of the product and combinations of other factors. Quantity Supplied = S(Price, Contributing factors) Supply Function Curves are generally upward sloping. For example, Quantity supplied goes up as the price of rice goes up. The relationship between the supply and price can be represented algebraically and is called ‘supply function’. The supply function can be written as 12 ∫Sx = f(Px, FT, FI, Rp, W, E, N) Where Sx = Supply of product x Px = Price of product x FT = Factor of technology affecting supply FI = Factor of input prices affecting supply Rp = Related product price W = Influence of weather, strikes and other short run forces E = Expectation about future prospects for prices, costs, sales and the state of economy. N = Number of firms in the market (Competitions) The Law of Supply There is a direct relationship between price and quantity supplied. Quantity supplied rises as price rises, other things remaining constant. Vice versa, Quantity supplied falls as price falls, other things constant. Explanation As the price of a product rises; producers will be willing to supply more. The height of the supply curve at any quantity shows the minimum price necessary to induce producers to supply that next unit to market. The height of the supply curve at any quantity also shows the opportunity cost of producing the next unit of the good. The law of supply is accounted for by two factors: When prices rise, firms substitute production of one good for another. Assuming firms’ costs are constant, a higher price means higher profits. The Supply Curve: The supply curve is the graphic representation of the law of supply. The supply curve slopes upward to the right. The slope tells us that the quantity supplied varies directly – in the same direction – with the price. Short run supply In the short run the firm may face a fixed cost even if it produces no output, and we need to check whether it would be better off producing no output rather than producing some quantity. If it produces no output it makes a loss equal to FC. Thus the firm's optimal decision is to produce nothing if its best positive output yields a loss greater than FC, and otherwise to produce best positive output. Put differently, the optimal decision is to produce no output if the price is less than the minimum of the firm's average variable cost (in which case for every unit the firm sells it makes a loss). Long run supply In the long run the firm pays nothing if it does not operate. Thus its supply function is given by the part of its marginal cost function above its long run average cost function. (If its maximal profit it positive it wants to operate; if its maximal profit it negative it does not want to operate.) 13 Shift Factors of Supply Other factors besides price affect how much will be supplied are: Prices of inputs used in the production of a good, Technology, .Suppliers’ expectations, Number of Suppliers, Price of Related Goods or Services, and, Taxes and subsidies. Price of Inputs (Resource Prices): When costs go up, profits go down, so that the incentive to supply also goes down. Technology: Advances in technology reduce the number of inputs needed to produce a given supply of goods. Costs go down; profits go up, leading to increased supply. Expectations: If suppliers expect prices to rise in the future, they may store today's supply to reap higher profits later. Number of Suppliers: As more people decide to supply a good the market supply increases. Price of Related Goods or Services: The opportunity cost of producing and selling any good is the forgone opportunity to produce another good. If the price of alternate good changes then the opportunity cost of producing of a particular good changes too! Taxes and subsidies: When taxes go up, costs go up, and profits go down, leading suppliers to reduce output. When government subsidies go up, costs go down, and profits go up, leading suppliers to increase output. Price elasticity of supply (Pes) Pes measures the relationship between change in quantity supplied and a change in price. If supply is elastic, producers can increase output without a rise in cost or a time delay. If supply is inelastic, firms find it hard to change production in a given time period. The formula for price elasticity of supply is: % change in quantity supply / % change in price That is Percentage change in quantity supplied divided by the percentage change in price. When Pes > 1, then supply is price elastic When Pes < 1, then supply is price inelastic 14 When Pes = 0, supply is perfectly inelastic When Pes = infinity, supply is perfectly elastic following a change in demand What factors affect the elasticity of supply? Spare production capacity: If there is plenty of spare capacity then a business can increase output without a rise in costs and supply will be elastic in response to a change in demand. The supply of goods and services is most elastic during a recession, when there is plenty of spare labour and capital resources. Stocks of finished products and components: If stocks of raw materials and finished products are at a high level then a firm is able to respond to a change in demand - supply will be elastic. Conversely when stocks are low, dwindling supplies force prices higher because of scarcity in the market. The ease and cost of factor substitution: If both capital and labour are occupationally mobile then the elasticity of supply for a product is higher than if capital and labour cannot easily be switched. A good example might be a printing press which can switch easily between printing magazines and greetings cards. Time period and production speed: Supply is more price elastic the longer the time periodthat a firm is allowed to adjust its production levels. In some agricultural markets the momentary supply is fixed and is determined mainly by planting decisions made months before, and also climatic conditions, which affect the production yield. In contrast the supply of milk is price elastic because of a short time span from cows producing milk and products reaching the market place. Factors that affect the elasticity of supply Spare production capacity: If there is plenty of spare capacity then a business can increase output without a rise in costs and supply will be elastic in response to a change in demand. The supply of goods and services is most elastic during a recession, when there is plenty of spare labour and capital resources. Stocks of finished products and components: If stocks of raw materials and finished products are at a high level then a firm is able to respond to a change in demand - supply will be elastic. Conversely when stocks are low, dwindling supplies force prices higher because of scarcity in the market. The ease and cost of factor substitution: If both capital and labour are occupationally mobile then the elasticity of supply for a product is higher than if capital and labour cannot easily be switched. A good example might be a printing press which can switch easily between printing magazines and greetings cards. Time period and production speed: Supply is more price elastic the longer the time period that a firm is allowed to adjust its production levels. In some agricultural markets the momentary supply is fixed and is determined mainly by planting decisions made months before, and also climatic conditions, which affect the production yield. In contrast the supply of milk is price elastic because of a short time span from cows producing milk and products reaching the market place. Availability of raw materials 15 For example, availability may cap the amount of gold that can be produced in a country regardless of price. Likewise, the price of Van Gogh paintings is unlikely to affect their supply. Length and complexity of production Much depends on the complexity of the production process. Textile production is relatively simple. The labor is largely unskilled and production facilities are little more than buildings – no special structures are needed. Thus the PES for textiles is elastic. On the other hand, the PES for specific types of motor vehicles is relatively inelastic. Auto manufacture is a multistage process that requires specialized equipment, skilled labor, a large suppliers network and large R&D costs. Mobility of factors If the factors of production are easily available and if a producer producing one good can switch their resources and put it towards the creation of a product in demand, then it can be said that the PES is relatively elastic. The inverse applies to this, to make it relatively inelastic. Time to respond The more time a producer has to respond to price changes the more elastic the supplySupply is normally more elastic in the long run than in the short run for produced goods, since it is generally assumed that in the long run all factors of productioncan be utilised to increase supply, whereas in the short run only labor can be increased, and even then, changes may be prohibitively costly.[1] For example, a cotton farmer cannot immediately (i.e. in the short run) respond to an increase in the price of soybeans because of the time it would take to procure the necessary land. Excess capacity A producer who has unused capacity can (and will) quickly respond to price changes in his market assuming that variable factors are readily available. Inventories A producer who has a supply of goods or available storage capacity can quickly increase supply to market. Calculating the Price Elasticity of Supply PES = (% Change in Quantity Supplied)/(% Change in Price) Calculating the Price Elasticity of Supply Price(OLD)=9 Price(NEW)=10 QSupply(OLD)=150 QSupply(NEW)=210 To calculate the price elasticity, we need to know what the percentage change in quantity supply is and what the percentage change in price is. It's best to calculate these one at a time. Calculating the Percentage Change in Quantity Supply 16 The formula used to calculate the percentage change in quantity supplied is: [QSupply(NEW) QSupply(OLD)] / QSupply(OLD) By filling in the values we wrote down, we get: [210 - 150] / 150 = (60/150) = 0.4 So we note that % Change in Quantity Supplied = 0.4 (This is in decimal terms. In percentage terms it would be 40%). Now we need to calculate the percentage change in price. Calculating the Percentage Change in PriceSimilar to before, the formula used to calculate the percentage change in price is:[Price(NEW) - Price(OLD)] / Price(OLD) By filling in the values we wrote down, we get:[10 - 9] / 9 = (1/9) = 0.1111 We have both the percentage change in quantity supplied and the percentage change in price, so we can calculate the price elasticity of supply. Final Step of Calculating the Price Elasticity of Supply We go back to our formula of:PES = (% Change in Quantity Supplied)/(% Change in Price) We now fill in the two percentages in this equation using the figures we calculated. PES = (0.4)/(0.1111) = 3.6 17