lesson12

advertisement

Linux Memory Issues

An introduction to some low-level

and some high-level memory

management concepts

Some Architecture History

•

•

•

•

•

•

8080 (late-1970s) 16-bit address (64-KB)

8086 (early-1980s) 20-bit address (1-MB)

80286 (mid-’80s) 24-bit address (16-MB)

80386 (late-’80s) 32-bit address (4-GB)

80686 (late-’90s) 36-bit address (64-GB)

Core2 (mid-2000s) 40-bit address (1-TB)

‘Backward Compatibility’

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Many buyers resist ‘early obsolescence’

New processors need to run old programs

Early design-decisions leave their legacy

8086 could run recompiled 8080 programs

80x86 can still run most 8086 applications

Win95/98 could run most MS-DOS apps

But a few areas of incompatibility existed

Linux must accommodate legacy

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Legacy elements: hardware and firmware

CPU: reset-address and interrupt vectors

ROM-BIOS: data area and boot location

Display Controllers: VRAM & video BIOS

Support chipsets: 15MB ‘Memory Window’

DMA: 24-bit memory-address bus

SMP: combined Local and I/O APICs

Other CPU Architectures

• Besides IA-32, Linux runs on other CPUs

(e.g., PowerPC, MC68000, IBM360, Sparc)

• So must accommodate their differences

– Memory-Mapped I/O

– Wider address-buses

– Non-Uniform Memory Access (NUMA)

Nodes, Zones, and Pages

•

•

•

•

•

Nodes: to accommodate NUMA systems

However 80x86 doesn’t support NUMA

So on 80x86 Linux uses just one ‘node’

Zones: to accommodate distinct regions

Three ‘zones’ on 80x86:

– ZONE_DMA

– ZONE_NORMAL

– ZONE_HIGHMEM

(memory below 16-MB)

(from 16-MB to 896-MB)

(memory above 896-MB)

Zones divided into Pages

•

•

•

•

80x86 supports 4-KB page-frames

Linux uses an array of ‘page descriptors’

Array of page descriptors: ‘mem_map[]’

physical memory is ‘mapped’ by CPU

How 80x86 Addresses RAM

• Two-stages: ‘segmentation’ plus ‘paging’:

– First: logical address linear address

– Then: linear address physical address

• CPU employs special caches:

– Segment-registers contain ‘hidden’ fields

– Paging uses ‘Translation Lookaside Buffer’

Logical to Linear

segment-register

virtual address-space

operand-offset

selector

global descriptor table

descriptor

GDTR

base-address

and segment-limit

memory

segment

Segment Descriptor Format

31

0

Base[ 31..24 ]

Base[ 15..0 ]

Limit

[19..16 ]

Base[ 23..16 ]

Limit[ 15..0 ]

Linear to Physical

linear address

dir-index

table-index

offset

physical address-space

page

table

page

directory

CR3

page frame

CR3 and CR4

• Register CR3 holds the physical address

of the current task’s page-directory table

• Register CR4 was added in the 80486 so

software would have the option of “turning

on” certain advanced new CPU features,

yet older software still could execute (by

just leaving the new features “turned off”)

Example: Page-Size Extensions

• 80586 can map either 4KB or 4MB pages

• With 4MB pages: middle table is omitted

• Entire 4GB address-space is subdivided

into 1024 4MB-pages

Demo-module: ‘cr3.c’ creates a pseudo-file

showing the values in CR3 and in CR4

Linear to Physical

linear address

dir-index

offset

physical address-space

page

directory

page frame

CR3

4-MB page-frames

PageTable Entry Format

31

12 11

Frame Address

0

Frame attributes

Some Frame Attributes:

P : (present=1, not-present=0)

R/W : (writable=1, readonly=0)

U/S : (user=1, supervisor=0)

D : (dirty=1, clean=0)

A : (accessed=1, not-accessed=0)

S : (size 4MB = 1, size 4KB = 0)

Visualizing Memory

• Our ‘pgdir.c’ module creates a pseudo-file

that lets users see a visual depiction of the

CPU’s current ‘map’ of ‘virtual memory’

• Virtual address-space (4-GB)

– subdivided into 4MB pages (1024 pels)

– Text characters: 16 rows by 64 columns

Virtual Memory Visualization

•

•

•

•

•

Shows which addresses are ‘mapped’

Display granularity is 4MB

Data is gotten from task’s page-directory

Page-Directory location is in register CR3

Legend:

‘-’ = frame not mapped

‘3’ = r/w by supervisor

‘7’ = r/w by user

Assigning memory to tasks

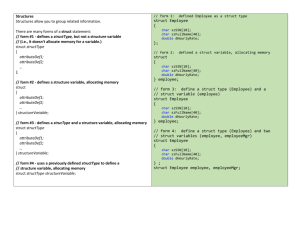

• Each Linux process has a ‘process descriptor’

with a pointer inside it named ‘mm’:

struct task_struct {

pid_t

pid;

char

comm[16];

struct mm_struct

*mm;

/* plus many additional fields */

};

struct mm_struct

•

•

•

•

•

•

It describes the task’s ‘memory map’

Where’s the code, the data, the stack?

Where are the ‘shared libraries’?

What are attributes of each memory area?

How many distinct memory areas?

Where is the task’s ‘page directory’?

Demo: ‘mm.c’

• It creates a pseudo-file: ‘/proc/mm’

• Allows users to see values stored in some

of the ‘mm_struct’ object’s important fields

Virtual Memory Areas

• Inside ‘mm_struct’ is a pointer to a list

• Name of this pointer is ‘mmap’

struct mm_struct {

struct vm_area_struct

/* plus many other fields */

*mmap;

};

Linked List of VMAs

• Each ‘vm_area_struct’ points to another

struct vm_area_struct {

unsigned long

vm_start;

unsigned long

vm_end;

unsigned long

vm_flags;

struct vm_area_struct *vm_next;

/* plus some other fields */

};

Structure relationships

The ‘process descriptor’ for a task

Task’s mm structure

task_struct

mm_struct

*mmap

VMA

*mm

VMA

VMA

VMA

VMA

Linked list of ‘vm_area_struct’ structures

Demo ‘vma.c’ module

• It creates a pseudo-file: /proc/vma

• Lets user see the list of VMAs for a task

• Also shows the ‘pgd’ field in ‘mm_struct’

EXERCISE

• Compare our demo to ‘/proc/self/maps’

In-class exercise #2

• Try running our ‘domalloc.cpp’ demo

• It lets you see how a call to the ‘malloc()’

function would affect an application list of

‘vm_area_struct’ objects

• NOTE: You have to install our ‘vma.ko’

kernel-object before running ‘domalloc’