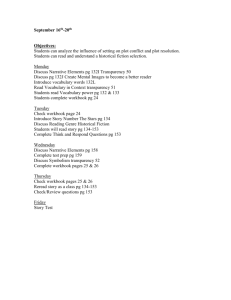

Needs Assessment

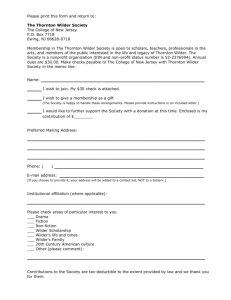

advertisement