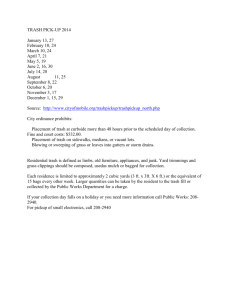

case study i: the la river basin

advertisement

Ned Weidner

Configurations Submission

Theories I could add: Jane Bennet’s Vibrant Matter: where encounters with landfills

serves as examples of thing power. The Anatomy of Disgust, Urban Smellscapes,

Historical Perceptions of Scent.

Since I want to write about a smell becoming a controlled sense in Southern California or

at least attempting to become a controlled sense, I should mention the fact that gardens

played a big role in the history of the development of SoCal. People gardened as a way

to control the wild, both the way it looked and smelled. Beautiful flowers emit a lovely

smell that masks other unsavory smells. In Southern California, “Gardens functioned as

economic institutions: they were either factory-like landscapes producing wealth or

places of conspicuous cultivation that deilineated social status” And certainly the smell of

those landscapes came to stand in for that status, which is why

Waste in the Bataillian sense is a critical expenditure.

Abstract: This essay uses smell of rotting fish and animal excrement as a mapping tool to

analyze three case studies of areas in Southern California where human-animal

communities have been marked as trash. The analysis illustrates the ability of smell to

rupture the social order and social imaginary of Southern California. Keywords: Trash

animals, Georges Bataille, smell, consumption, social order.

The Smell of Death and Excrement: Mapping Southern California Trash

Communities

“Bad odours make myth and life possible, but they also threaten to undo both.” –

Nils Bubant1

When I first moved to Southern California in the summer of 2012, my nostrils

were overtaken by the lingering stench of rotting eggs. It didn’t matter where I went in

the Southland. If I drove to the Inland Empire, the putrid stench followed me. If I

travelled to Orange County, it was there as well. The stench had seemingly infiltrated

every corner of the greater Los Angeles area. I had many negative preconceived notions

Nils Bubant, “The Odour of Things: Smell and the Cultural Elaboration of Disgust in Eastern

Indonesia,” Ethos: Journal of Anthropology 63:1 (1998): p. 48.

1

1

about Los Angeles before apprehensively picking up stakes and moving there, but the

constant smell of rotting eggs for what seemed like a week was not one of them. It wasn’t

until later I learned the stench emanated from the putrefaction of two million rotting

tilapia on the shores of the Salton Sea over a hundred miles away from the city. The story

of the Salton Sea and its rotting fish is not necessarily a unique one in Southern

California. In fact, we can learn a lot about the history of Southern California and its

inhabitants by mapping sites of putrefaction and foul smelling excrement.

In this essay I analyze three sites the L.A. River Basin, the Salton Sea, and the La

Jolla Cove, as sites of Southern California trash communities, or places where trash in its

varying rhetorical renderings is the common denominator in marking the people and

animals that inhabit the social space of the community. This analysis illustrates how the

stench from rotting fish or foul smelling animal excrement served as a catalyst for social

change, a contributing factor in attitudes towards living beings, a sensual encounter with

our own animality, and a rupture of social order and the social imaginary of Southern

California. In each case study, smell played a roll in the formation of attitudes about the

place and the living beings that inhabit it. Taken together these trash communities map a

collage, which mark Southern California territories of homogenous society.2

DEFINING TRASH COMMUNITIES

Trash is a material result of consumption, but truly it is much more. It is

embedded within identity. It is a cultural metaphor. As a term of classification, “it

defines for us the ways we understand and act towards certain inanimate or animate

2

Georges Bataille, The Accursed Share Volume I: Consumption, Bataille describes homogenous

society as one wherein everything accepted and considered a part of that society works together

in a predictable, rational way to form a smooth operating productive system.

2

objects.”3 Trash also often carries with it an olfactory signifier. Trash stinks. Waste and

excess are closely linked with trash for they too are linked with identity and can be

considered useless or lower status. But waste also can be lavish expenditure, dissipation,

destruction, and death. It can mean a decline as in wasting away.4 And excess can be

spent in luxurious manner. All are results of the process of consumption.

According to Georges Bataille’s theory of consumption, “life is a continuous

production of energy that needs to expend itself.”5 We consume in order to fulfill our

humanity. The expenditure of this energy results in either lavish expenditure or is caste

aside as what Mary Douglas might term “matters out of place.” If the waste is spent

luxuriously in the arts or in building massive ocean viewed real estate or in spectacle, it is

perceived as something that promotes homogeneous society, even though as Bataille

argues it never truly does. But on the other hand if this energy is caste aside as useless

waste, it becomes a part of heterogeneous society. Logic used to describe a thing as

useless or valueless extends to both humans and animals. Thus trash communities are a

part of the heterogeneous world. According to Bataille we should be living in a world that

is fully heterogeneous, meaning we understand that waste is an important part of life and

act according to the past, present, and future not simply the now. To live in this way

would be for him to truly live in sovereignty because we would have foresight of our

actions of consumption. Instead we consume with little vision. Legacies of this blind

consumption are many and varied. Trash, concreted rivers, and accidental inland seas are

Kelsi Nagy and Phillip David Johnson II, “Introduction,” in Trash Animals: How We Live with

Nature’s Filthy, Feral, Invasive, and Unwanted Species, ed. Kelsi Nagy and Peter David Johnson

II (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013) p. 241. E-book.

4

Susan Strasser, Waste and Want: A Social History of Trash (New York: Owl Books, 1999) p. 5.

5

Simonetta Falasca-Zamponi, Waste and Consumption: Capitalism, the Environment, and the

Life of Things, (New York: Routledge, 2011) p. 47.

3

3

just a few of the examples of the legacy of blind consumption. Trash animals and trash

communities are another.

Trash animals, as Kelsi Nagy explains, are those animals “that carry the myths,

symbolisms, stories, and violence of human history.”6 They can often thrive or benefit

from industrialization, and are often described as worthless, useless, disposable, or a

nuisance. Often we think of trash animals as those that have no economic value. Trash

animals are those that live in and sometimes thrive off of the waste of human society. As

will become clearer throughout this essay, the concept of trash animals encompasses

those that inspire human vitriol or indifference, are considered worthless, smelly, a

nuisance, “slide into roles as symbols of human fear or frustration,” or are associated with

industry and waste. It is for these reasons and others that trash animals become assigned

the “lowly order of our modern bestiary.”7

Yi-Fu Tuan argues that animals are a social group wrapped up in the same

struggle as humans.8 They are so important to the structure of human life and “so tied up

with (human) visions of progress and good life that humans have been unable to fully see

them.”9 Human outsider groups are ensnared in the same discourses as animal groups

that have been reviled or marked as trash.10 The community connection between humans

and trash occurs when similar rhetoric is used to describe the people that live with and

sometimes depend on trash animals like the residents living around the Salton Sea and the

Nagy, “Introduction” (above, n. 3), p. 197.

Ibid.

8

Yi-Fu Tuan, Dominance and Affection: The Making of Pets, (London: Yale University Press,

2004)

9

Alice Hovorka, “Transspecies Urban Theory: Chickens in an African City,” Cultural

Geographies, 15:1 (2008): p. 98.

10

Chris Philo, “Animals, Geography, and the City: Notes on Inclusions and Exclusions,” in

Animal Geographies: Place, Politics, and Identity in the Nature-Culture Borderlands, (London:

Verson, 1998) pp. 61-63.

6

7

4

homeless living in the L.A. River Basin; both are marked as trash or as waste products.

And so a trash community is a space where human and non-human animals, who are

marked as waste or excess, live in a symbolic and at times symbiotic relationship with

each other. As I complicate the meaning of waste and excess later, we will see that what

can be constituted as a trash community depends upon how we define and understand

waste.

THE SMELL OF SOCIAL SPACE

Trash communities sit both within and outside the boundaries of homogenous

society. The heterogeneous is often taboo, disordered or violent. The smell of trash

communities is the heterogeneous effusion. It haunts society and is a persuasive

illustration of the power of smell in the human condition. While these four sites span

across one-hundred years and nearly two-hundred and fifty miles, they are connected by

the common denominator that all of them serve as examples of the power of smell to

disrupt the order of social space and the social imaginary of Southern California. The

social order of space in Southern California is planned in order to promote

industrialization and consumption as well as perpetuate the social imaginary of Southern

California as a place where dreams and wealth are made.11 As this essay shows, when

foul smells seep into the confines of this order it ruptures this social imaginary.

Henri Lefebvre argues we only come into contact or are made aware of the order

of space when we have a problem with it or confront it physically. Lefebvre’s thesis in

11

The social space of Southern California is made to mask the conditions of production. It is a

Disneyland-like world created through and masked as a simulacrum of nature. See, Edward Soja,

Postmodern Geographies: The Reassertion of Space in Critical Theory, (London: Verso, 1989)

pp. 190-222.

5

The Production of Space is that all space is produced and organized through the logic of

capital and that the politics of that space adheres to the ideology of the state.12 The

ideology of the state is reflected in the social imaginary of the place or in the way a place

is perceived. The history of the production of space for Lefebvre is one of domination

and appropriation. It is a history that hides the modes of production and consumption.

Nowhere is this history more evident than in the simulacrum of ordered space of

Southern California. According to Georges Bataille the ordered, organization of social

space is an expression of sovereignty.13 When something disrupts that order, it disrupts

the ideology and myth of sovereignty that structures it.14 Usually the disruptive thing is a

war or event. In the case of this essay, it is the foul smell emanating from trash

communities that makes us aware of the order of space and disrupts the myth of

sovereignty.

An intricate study of smell in the West can create a deeper understanding of how

power is distributed throughout social space.15 We tend to undervalue our sense of smell

in creating our experience of everyday life because at first glance we do not rely upon it

as much as dogs or lions, but our sense of smell plays a central role in the construction of

our daily lives and has helped shape the humans we are today.16 Smell and odor, as

12

Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space, trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith, (Oxford: Blackwell

Publishing, 1991).

13

Alan Stoekl, Bataille’s Peak: Energy, Religion, and Postustainability, (Minneapolis: University

of Minnesota Press, 2007).

14

For Bataille the myth of sovereignty is that humans consume in order to be human, in order to

be sovereign, but the reality is that we do not consume with foresight and the legacy of our

consumption has ecological and social effects. If we were truly sovereign we would think about

the past, present, and future when consuming instead of doing so blindly.

15

Bubant, “The Odour of Things,” (above, n. 1) p. 49.

16

Gordon Shepard, Neurogastronomy: How the Brain Creates Flavor and Why it Matters. (New

York: Columbia University Press, 2011) p. 224.

6

Gaston Bachelard has argued are catalysts for myth formation.17 Smell lubricates our

ways of understanding, interacting, and being in the world. Today, olfaction infiltrates

every part of society from food production, clothing manufacturing, to landscape design.

We have tried to produce an ordered, pleasant smelling world – a homogenous society.

Smells that do not fit the mold of homogenous society are often hidden in industrial

zones, as is the case with slaughterhouses or tucked away in the countryside, as is the

case with landfills or sanitized. Exterminating odors from society and recreating order

was one of modernity’s primary goals.18 We built sewers and toilets, gardens and

perfumeries, we “declared war on all constraints of nature dared impose upon rational

moral humanity.”19 Foul smells were hidden from society in a similar nature to the way

death and mortality were kept a secret. Both undermined human sovereignty and did not

contribute to pleasant renderings of social imaginary of places. The odors of

decomposition were hidden, flushed in order to maintain the necessary social order of

homogenous society.20

Hiding foul odors is an olfactory illusion of sorts, which masks what Slavoj Zizek

might call the “real, impossible kernel.”21 An example of how we mask reality is

illustrated by the strategic placement of slaughterhouses. As cities modernized, the foul

smells of killing yards were pushed further out in part due to their horrid smells and as a

Bubant, “The Odour of Things,” (above, n. 1) p. 48

Zigmaunt Bauman, “The Sweet Smell of Decomposition,” Forget Baudrillard?, eds. Chris

Rojek et al. (New York: Routledge, 1993) p. 22.

19

Ibid 30

20

Ibid 30

21

There is also a deeply psychological and libidinal connection in the creation of ideological

olfaction, which this essay simply does not have the space to address. Slavoj Zizek, The Sublime

Object of Ideology, (London: Verso) p. 45.

17

18

7

way to mask the conditions of production.22 According to Zizek, “The function of

ideology is not to offer us a point of escape from our reality but to offer us the social

reality itself as an escape from some traumatic, real kernel.”23 As we will see throughout

this essay the putrid stench of death and excrement stemming from trash communities

calls forth a forgotten or hidden essence of our own reality. The reality being that despite

our efforts we are human-animals fully immersed in the natural world. The stench of

putrefaction can involuntarily draw forth kernels of pure truth by rupturing the order of

homogenous society. This essay is an illustration of that rupture.

CASE STUDY I: THE L.A. RIVER BASIN

“Los Angeles is a dung-heap…it is a huge, shallow toilet bowl.” – Peter Plagens24

The L.A. River smells. When walking, biking, or fishing along it one cannot

escape the rotten stench of waste emanating from its putrid waters.25 Smell is indexical.

When one inhales the putrid stench of the river they are in fact inhaling molecules of

mercaptan, or a common component of biological putrefaction that can make wastewater

smell. When people inhale this they are literally sensually consuming the biological

22

Chris Philo illustrates how slaughterhouses in the US and London were strategically placed

outside of city centers because their presence in city centers disturbed the order of the city. See,

Chris Philo, “Animals”, (above, n. 10) pp. 61-63.

23

Zizek. Sublime. (above, n.21) p. 45

24

Peter Plagens. Los Angeles Times. qtd in William Alexander McClung, Landscapes of Desire:

Anglo Mythologies of Los Angeles, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002) p. 226.

25

While I have smelled this stench many times myself, there are countless reports in the LA

Times and other media outlets remarking about the putrid stench of rotten eggs coming from the

river. See, Louis Sahagun, “Search for Elusive Trout in the Los Angeles River,” LA Times,

http://www.latimes.com/local/la-me-adv-steelhead-search-20140517-story.html

8

history of homogenous society. Tracing the history of the river allows us to understand

the importance of this smell.

The L.A. River was reconstructed to fit the order of social space and imaginary of

Los Angeles. It was once an idyllic stream where the first Spanish explorers were

overtaken by its beauty so much so that they named the basin El Pueblo de Nuestra

Señora la Reyna de Los Angeles de Porciúncula in homage to a sacred religious site in

their homeland.26 Now escorted through the urban landscape as a mummified simulacrum

of a river, the Los Angeles River is a prime example of how an entire landscape has been

made to disappear through the processes of consumption. The river sits just out of plain

view to the busy Los Angeles commuter. It is hard to make out the snaking contours of a

riverbed or the sloping angles of rapids and eddies behind the billboards begging you to

buy Manny Ramirez gear or shuffling you to Dame Edna’s last show. It is a river so

forgotten, so abused, so maligned that few even know it exists. The fact that so many

people unknowingly come in contact with this landscape by either consciously choosing

to ignore it or who are subconsciously blinded by social stigmas of waste and trash

speaks to a society’s need to order, to purify, and to punish the unclean. As Mary

Douglas taught us, our desire for cleanliness is an ideological one driven by the desire for

a homogenous society.27

Today an urban ghost, the L.A. River is the mummified remains of a river. It has

been described as a “mass of filth,” as a cesspool for the rotting remains of horse

26

Blake Gumprecht, The Los Angeles River: Its Life, Death, and Possible Rebirth, (Baltimore:

John’s Hopkins University Press, 2001) p. 2.

27

Mary Douglas, Purity and Danger: An Analysis of the Concepts of Pollution and Taboo,

(London: Routledge, 1984) 615. E-book.

9

carcasses and putrefying dead bodies.28 Historically the river has been essentially a

dumping ground for all things unwanted. People hoped the fluctuating water level would

carry the products of their increasingly excessive lives away, essentially using the “foul

stream…as a dumping-ground for the refuse of the city.”29 Property owners dumped

manure from stables, piles of sawdust, decaying vegetables, and foul-smelling refuse

from restaurants into the wretched morass they had created.30 The city’s water supply was

being polluted by the very people that depended on it for survival. Angelenos polluted in

blind consumption.

As Los Angeles transitioned from a village to an ordered urban space, the river

transformed from an idyllic stream to a mass of filth and eventually into a controlled

ordered waste stream. By 1939 because of its destructive tendency to flood as much as its

foul smells and usage as a sewer, the river was buried in a concrete sarcophagus with the

US Army Corp of Engineers acting as executioner.31 Because of its polluted condition,

the L.A. River had died long before the last nail was place in the coffin by the US Army

Corps of Engineers32, and dead things even if it is a river operate on the psychological

level of fear and repulsion, and so they are embalmed and buried. Thus the L.A. River

was metaphorically buried in a concrete box to be forgotten and eventually, completely

disappear.

The L.A. River itself might be considered trash. It is figuratively the excremental,

unwanted waste of Los Angeles and a historical reminder of the destructive powers of

capital. In its reality as a wastewater channel, the river is quite literally, a present day

“A Mass of Filth,” Los Angeles Times, January 26, 1896.

Ibid

30

Ibid

31

Gumprecht. Los Angeles River. (above, n. 26) p. 3.

32

Gumprecht. Los Angeles River. (above, n. 26) p. 129.

28

29

10

vision of bodily excrement and waste. The river has become in the words of Jenny Price

“the Death Star to American nature lovers.”33 It is often considered the most unnatural

river landscape in the country. But Price argues there is no better place than L.A. to think

about nature. And the L.A. River she says is “where all possible kinds of nature stories in

L.A converge.”34 Price is correct. The L.A. River is perhaps the best place, better than

Crater Lake or Yosemite, to think about nature because in its degraded state it challenges

our very notions of the natural and forces us to analyze its everydayness. In this analysis

we see that humans and human development are not abstract from nature but deeply

embedded within it.

Living in and along the L.A. River today is the epitome of a trash community. Its

concrete banks and what is left of the riparian habitat are riddled with communities of

homeless people living in encampments. 35 Lying in the river’s turbid depths Cyprinus

carpio, or the common carp, thrives in this oxygen-diminished environment. In their utter

connection to waste,36 these humans and animals that call the L.A. River home are

Jenny Price, “Thirteen Ways of Seeing Nature in L.A.” The Believer, April 2006.

Ibid.

35

Homeless were not always considered as wastrels. They were once considered people who

wanted the free world of the open road as is illustrated in Walt Whitman’s “Song of the Open

Road.” The decades between 1870-1920 saw a huge increase in homeless Americans. As the

country transitioned from agrarian society to industrial, farmers and shop owners left their homes

and took out in search of work. Many of those people headed west and many of those came to

Los Angeles. Perhaps partly spurned by the Whitmanian promise of the ‘open road’ as much

perhaps as they were by the fact that the rise of commercial exchange eroded the protection of

developing a personal bond with your employer. The rise of homeless across the U.S. meant that

many people were in search of inexpensive food sources. Carp were seen as a way to satisfy this

need. Their discourses of exclusion connect because both the homeless and carp are considered

valueless often, non-entities. See, Todd Depastino, Citizen Hobo: How a Century of

Homelessness Shaped America, (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2003)

36

Carp were not always considered trash animals. Due to their incredible fecundity and value as a

game fish in Europe, carp were once sought after and intentionally introduced to North American

Waters. They were introduced to satisfy the growing needs of tramps and working class

Americans who wanted an inexpensive meal.36 But their connection to polluted waters, and the

poor, often colored people who ate them turned them into what Phillip David Johnson II calls “a

33

34

11

symbolic of the history of the urban space that we know as Los Angeles. These people,

these animals are the living embodiment of what Douglas terms “matters out of place.”37

Their presence and perception makes visible the margins of the socially acceptable. They

are the waste product of capitalism’s endless self-reproduction. Becoming aware of them

reveals a historical blind spot and puts us into contact, at least passively, with ourselves

as historical beings by forcing us to confront the effects of our consumption.

Some of the homeless encamped along the riverbank use the carp for food. Most

call the other animals also related to trash like pigeons and raccoons their companions.38

The symbiotic circle is fulfilled as some of the homeless feed their animal friends scraps

of bread and dog food. Bread in the diet of the carp is so common that the best carp flyfishing technique on the river is to use a sunken-bread imitation fly or as it is locally

known a tortilla fly. Living in utter invisibility, the carp and the homeless are the

invisible waste products of consumption.39 They live in the filtered liquid remains of

human excrement.40

valueless nonentity or pest and a shadowy inhabitant of urban park ponds and polluted lakes and

rivers.” By the 1920’s the carp had become fully considered a trash fish. See, Phillip David

Johnson II, “Fly-Fishing for Carp as a Deeper Aesthetic,” in Trash Animals: How We Live with

Nature’s Filthy, Feral, Invasive, and Unwanted Species, eds. Kelsi Nagy and Phillip David

Johnson II (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013) p. 3889. E-book

37

Douglas, Purity, (above, n. 27) p. 315.

38

I am currently conducting ethnographic research on the some of the homeless communities

living along the river. One reappearing theme is the familial connection many homeless have to

wild and domestic animals. Other researchers have made similar claims including Jennifer

Wolch et al. in “Constructing the Animal Worlds of Inner-City Los Angeles,” in Animal Spaces,

Beastly Places: New Geographies of Human-Animal Relations, eds Chris Philo and Chris

Wilbert, (London: Routledge, 2000) pp. 71-98.

40

According to a number of LA Times and San Francisco Call articles, the introduction of the

carp into the US is seen as a curse or a mistake. The fish were also racialized in their connection

to the poor people of color how ate them. One article argues carp had “become common and

worthless, and only the Chinese will handle them.” Like the Chinese they were considered

enemies of the state.

12

The homeless and their smell do not fit the social imaginary of Los Angeles.

Walking along the L.A River it is both the sight and smells of them that people find

disturbing.41 Photojournalist Francine Orr, who took photos for LA Times audio slide

show on the state of the homeless communities in the river called “Gimme Shelter,” cited

the smell emanating from these communities as being an issue when shooting. It smells

so bad, she says that many of the homeless lose their sense of smell. Today there are

people, like Friends of the L.A. River (FoLAR) who want to revitalize the L.A. River, to

bring it back to life. Even Mayor Eric Garcetti is on board with the plan. Part of the

revitalization process includes removing the smell and waste from unwanted homeless

encampments because the city argues they pose a criminal and public health threat by

defecating and urinating along the banks.42 The truth is the L.A. River, homeless, and the

smell of both undermines the social imaginary of Los Angeles as being a place where

dreams are made.43 And so they must be removed.44

The poetry of L.A. River advocate Lewis McAdams speaks to the very heart of

the utter despair and grotesque symbolism of the river and its “bottom-feeders.” His

poem “Hymn to the Bottom Feeders” draws together the living and the dead in an ode to

trash communities of sorts. McAdams calls the river “toxic-waste” thanks to the

excessive dumping of industrial waste in the stream. And with a tone as somber as the

41

Part of my ethnographic work on the trash communities of the river involves interviewing other

locals who use the river as recreation. Many people site the smell of the homeless encampments

as being more disturbing than the site of them as many of them are not fully in the field of vision

for bikers and runners.

42

Brenda Gazzar, “Fighting to Survive: A Look at Long Beach’s Chronically Homeless,” PressTelegram News, http://www.presstelegram.com/general-news/20130817/fighting-to-survive-alook-at-long-beachs-chronically-homeless

43

Soja, Postmodern, (above, n. 11)

44

Carp eradication practices began happening in Los Angeles River Basin and across California

in the early part of the twentieth-century. Around the same time city officials first began to

confront what they called Los Angeles’ homeless problem.

13

slow moving current of the river itself, McAdams draws a direct line between

consumption, excess, and the utter vitriol and disgust some people have for the bottom

feeding homeless and carp.

“Hymn to the Bottom Feeders”

Open up a storm drain manual

To characters out of Joel-Peter Witkin – flabby,

Masked, and naked; staring up at us

From an undersea tableau of ooze

Pieces of body parts float

To the surface, the

Whitish bellies of bottom feeders:

Catfish, tilapia, carp.45

McAdams calls attention to the connection between industrial waste and death

and decay by invoking the grotesque, shocking work of Joel-Peter Witkin, whose work

“represents post-mortem flesh as an actively decaying produce of death.” 46 It is clear that

the storm drain characters references the homeless who often make their tents in the

concrete enclaves of storm drains, which open into the river. As the whitish bellies of the

catfish, tilapia, and carp float to the surface, McAdams draws our attention to the horrors

of industrial development, eloquently naming the “caustic soda” courtesy of industry and

blind consumption as one of the contributing elements to the death of the L.A. River.

McAdams poetry is a ghostly cultural illustration of the entanglements between humans

and animals in the L.A. River trash community. Carp and homeless stand in as symbols

of the ecological destruction of Los Angeles. They remind us that waste too is an

Lewis McAdams, “Hymn to the Bottom-Feeders,” in The River: Books I, II, III, (San

Francisco: Blue Press, 2007) p. 26.

46

Sarah Bezan, “From the Mortician’s Scalpel to the Butcher’s Knife: Towards an Animal

Thanatology,” Journal for Critical Animal Studies 10:1 (2012): 119.

45

14

important, living, component of society. The abhorrence of such things draws attention

to human taboos and misunderstandings of life. Nowhere is this abhorrence more evident

than with the history of “Nigger” Slough.

THE UNFORTUNATE HISTORY OF “NIGGER” SLOUGH

“It is rarely one’s own group, which smells.” – Constance Classen47

As we uncover the remains of the L.A. River we find ghosts tales that tell of

racism, death, and piles of rotting fish. One such history is that of “Nigger” Slough. The

history of “Nigger” Slough illustrates what happens when the power of smell ruptures

the social order. As described earlier, the L.A. River was prone to flooding. These floods

would sometimes create huge backwater sloughs. “Nigger” Slough was perhaps the

largest of such sloughs. The slough, which extended from Gardena to nearly Torrance to

the West and Lomita to the South, was a swampy backwater lake popular with duck

hunters. The history of the slough like its waters is muddy. Because of its connection to

spring runoff its water levels fluctuated, so mapping its exact location is somewhat of a

subjective task.

According to local newspapers the place got its name because most of the

residents surrounding the slough were of African descent; those who were not were often

tramps.48 There was a large ranch on the slough owned by George Carson, but rented by

47

Constance Classen et al., Aroma: The Cultural History of Smell, (London: Routledge, 1994)

165.

48

“New Name for Nigger Slough: Old Title’s History Revealed,” Torrance Herald, March 31,

1938.

15

an African-American man named Edison who operated it as a hog farm.49 Beyond its

usage as sporting ground and hog ranch, “Nigger” Slough was often depicted as a place

of ill repute. There are more than a few stories of mysterious deaths occurring in the

slough and often it was referred to a nuisance both because of its “deadly odors”50 and its

ability to spread malaria.51 We must remember that the late 19th C was firmly embedded

with miasmic theory or the belief in the ability of foul smells and odors to transmit

diseases. The slough, like the people who lived around it and the animals who survived

in it was associated with disease and death. They were part of heterogeneous society.

They represented the excess of the L.A. River and the waste of homogenous society.

They were what Bataille might call, “death in the midst of things that are well ordered.”52

They simultaneously were caste out from that social order and through the power of their

smell disturbed it.

When the river did not provide freshwater to the slough, which was in the late

nineteenth and early twentieth-century rare, the surface of the water was filled with scum

and varying red hues, making the appearance of the water “simply frightful.”53 The bank

would swarm with flies and if a pebble was thrown into the water, bubbles would rise to

the surface, “making one shudder to think of what may be underneath.”54 The slough like

much of the water in the L.A. River Basin was also a dumping ground for horse carcasses

“A Public Nuisance: The Frightful Condition of ‘Nigger’ Slough,” Los Angeles Times,

September 12, 1894. p. 7.

50

“The ‘Nigger Slough’: The Situation as to Abatement of the Nuisance,” Los Angeles Times,

August 3, 1895.

51

“Nigger Slough Said to be the Cause of Malaria,” Los Angeles Herald, 25 Oct 1893.

52

Bataille, The Accursed Share Volume III, (above, n. 2) p. 216.

53

“A Public Nuisance,” (above, n. 49). p. 7.

54

Ibid.

49

16

and other dead putrefying animals. Edison’s hogs would often pick the bones of

decaying horses and dogs clean. Leaving behind only carcasses to rot dry in the arid sun.

When the putrid stench from the carcasses of rotting fish carcasses seeped into the

social space of homogenous society it became a threat to the social imaginary of Southern

California. In the summer, the slough water would partly dry up and recede. The carp

were so abundant they sucked up the oxygen in the receding slough and would die by the

thousands on its muddy banks. They would rot and putrefy creating a smell so bad it

incited social action. When the ocean breeze picked up, residents as far wide as Redondo,

Compton, and Gardena complained of the stench emanated from these “masses of

putrefying fish.”55 Residents petitioned city hall to do something about the problem. The

L.A. times reported:

“The stench from the decaying fish gradually became worse

and early in July aid was invoked of the Supervisors….to see to

the clearing of the putrid mass from a part of the shore. The

work was extremely disagreeable, the odor being almost

overpowering. Men employed on it were frequently taken with

vomiting.”56

The stench from the rotting fish dropped land prices and residents complained of

illnesses.57 It became just another reason for controlling the river’s flow. It also did little

to feed into the belief that carp were somehow responsible for pollution, which further

“A Foul Mess: The Filthy Condition of the Nigger Slough,” Los Angeles Times, August 2,

1895.

56

“A Public Nuisance,” (above, n. 49). p. 7.

57

“Nigger Slough is Doomed,” Los Angeles Herald, December 22, 1894.

55

17

entrenched carp as a trash fish. Eventually “Nigger” Slough was renamed Laguna

Dominguez and then shortly thereafter it was drained and filled to make room for houses

spurred by Southern California urban sprawl.58 This restored the threat to the social order

of homogeneous society.

Fear and olfaction are subjective. The “Nigger” Slough “stench line” lawsuit is a

prime example of this subjectivity. When landowners sued the State of California citing

the slough as “a nuisance and menace to the health and happiness of the public,”59 they

named thirty defendants. All of which were white landowners in the area and included

the Security Loan and Trust Company, the German American Savings Bank and “some

of the best known business men…in this county.”60 Only one of which however, owned

land directly adjacent to the slough, Mr. George Carson. Interestingly reports of the smell

from “Nigger” Slough only came from white residents. Perhaps this is because AfricanAmericans did not have much of a voice at the time, or perhaps it is due to what Mark

Smith argues in How Race is Made that sensory stereotypes reinforced racial categories.

As he writes, “Foul stench emanating from blacks and their neighborhoods, suggested

that the nose could detect and thereby define blackness.”61

Was the stench really that bad or were white Angelenos simply reacting and

commenting on a broader set of racial and class based issues of Southern California?

Perhaps the answer does not matter. What is certain is that Angelenos were constructing

judgments and drawing clear divisions between species and one of the measuring sticks

“Scenes on First Section of New Harbor Boulevard, Now Being Built to San Pedro,” Los

Angeles Herald, October 10, 1909.

59

“Nigger Slough is Doomed,” (above, n. 57).

60

Ibid.

61

Mark Smith, How Race is Made: Slavery, Segregation, and the Senses, (Chapel Hill, University

of North Carolina Press, 2006) p. 184.

58

18

was smell. As Constance Classen reminds us, “Odors form the building blocks of

cosmologies, class hierarchies, and political orders; they can enforce social structures or

transgress them, unite people or divide them, empower or disempower.”62 The odor from

the rotting carp in “Nigger” Slough was powerful enough to unite white Angelenos

against neighboring African-Americans, squatters, and carp because it threatened the

sovereignty of homogeneous society. The power of the rotting fish also speaks to our fear

of death and decay.

Our fear of death and decay is related to our fear of the Other.63 This fear stems

from what Alan Badiou might call a violent sensual encounter with the animal.64 This

encounter can happen through olfaction as easily as it can any other sense. Bataille argues

our abhorrence of animality is an “abhorrence of all that is not useful.”65 Animality for

Bataille represents the uselessness of life. Animality has been wiped clean from the

consciousness of late modern homogenous society because we cannot permit “horror {as

in the horror of animality to} enter into considerations.”66 According to Bataille it is this

horror of animality that causes difference and the reason we separate human and animal

kind into classes.67 Trash animals and trash communities like the one in “Nigger” Slough

rest low in the social order of classes.

Using capitalistic rhetoric Americans have tried to paint a picture of life’s bounty

as progressing forward, growing, and expanding, but death and decay and animality are

as much a part of life as the nursery of the womb. In fact if we are to think of the fish of

62

Classen, Aroma, (above, n. 47) p. i.

Michael Richardson, Georges Bataille: Essential Writings (Los Angeles: SAGE, 1998) p. 202

64

Alan Badiou, Being and Event, trans. Olive Feltham (New York: Continuum Books, 2007)

65

Shannon Winnubst, “Bataille’s Queer Pleasures: The Universe as Spider or Spit,” in Reading

Bataille Now ed. Shannon Winnubst, (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2007) p. 1209.

66

Bataille, The Accursed Share Vol III, (above, n. 40) 117

67

Shannon Winnubst, “Bataille’s,” (above, n. 66)

63

19

“Nigger” Slough and the carp eating homeless of the wastewater of the L.A. River then

we are not contemplating simply the maggots and swarming flies that make our stomachs

turn or the fetid stench of a flaccid eddy of L.A. River wastewater. Rather we are

contemplating nature – the very essence of it. As Bataille writes, “life is a product of

putrefaction, and it depends on both death and the dungheap.”68 All of our bodies will

one day decompose into the earth from which we came. The aversion we feel toward the

stench and conditions that create putrefaction is an aversion to the very essence of life

itself and representative of our abhorrence for our own animality. Our reaction to these

aversions tells us about a society’s urge to remain ordered, homogenous, and human both

in form and sensuality.

CASE STUDY II: LA JOLLA COVE

“Waste is simultaneously divine and satanic. It is the midwife of all creation – and it its

most formidable obstacle.” – Zygmaut Bauman69

Bataille argues our aversion to death and decay is closely related to our aversion

to excrement.70 We cleanse ourselves of it in white porcelain bowls as if to somehow

assuage our disgust of the putrid substance. We flush it. And then we forget it. The

excrement of our society is hidden, forgotten – like the L.A. River and the squatter

residents of Slab City – after wiping our asses of it, it disappears. But like the L.A. River

and the squatters, excrement never really disappears. Society deals with it in order for our

sovereignty is to remain intact. When nonhuman animals who do not share our aversion

68

Bataille, The Accursed Share Vol III, (above, n. 2) p. 81.

Zygmunt Bauman, Wasted Lives: Modernity and Its Outcasts, (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2004)

p. 22.

70

Bataille, The Accursed Share, Vol. III, (above, n. 2), p. 14.

69

20

for excrement and stench live and defecate in close contact with humans, it can as we

have seen rupture the social order and threaten human sovereignty. Another example of

the rupture of this social order is seen on the rocks of La Jolla cove.

La Jolla, California is only one-hundred miles from the L.A. River and only

slightly closer to the Salton Sea, but culturally it might as well be three-thousand. The

wealthy community of La Jolla with its picturesque coastline, scenic cove, and upscale

retail is Southern California’s attempt at a utopian beach town. It is not what we might

think of as a trash community, but in many ways La Jolla is the epitome of waste and

excess. La Jolla is a lavish display of excess wealth. Multi-million dollar homes perch

high above the crashing waves of the Pacific Ocean. Restaurant villas and ocean view

suites cuddle the cliff line as a beacon to the promise of productive expenditure and

excessive consumption. Southern Californians tend to think of La Jolla as a sleepy little

beach town. But La Jolla has a smelly secret. Its beaches are covered in sea lion,

cormorant, and seagull excrement. If dinning at one of these upscale restaurants above

the cove, the stench can be so bad it can turn your crème brûlée into a lukewarm custard

of seagull stool.

The odor has become so abhorrent that a citizen’s alliance has formed in the name

of stopping these pooping marauders of the sea. “A group called Citizens for the Odor

Nuisance Abatement is suing the city of San Diego and the state of California over the

foul odor caused by bird and sea lion poop at La Jolla Cove.”71 They aim to confront the

problem head on; claiming this is an issue caused by the city and state after banning

people from walking on the cove rocks. Since then hoards of cormorants, seagulls, and

Claire Trageser, “San Diego Sued Over ‘Foul Odor’ of Sea Lion and Bird Poop at La Jolla

Cove,” KPBS Radio News, December 27, 2013. http://articles.latimes.com/2012/may/21/local/lame-salton-sea-20120521.

71

21

sea lions have defecated so much that San Diego mayor Bob Filner in a statement

reminiscent of the age of miasmic theory declared “the accumulation of bird waste a

public health hazard,”72 and an “economic emergency.”73 The city had attempted to do

away with the problem by using falcons and dogs to scare away the birds to no avail.

The birds would come back and the “putrid, “noxious” smell of bird poop would return

with them.74 The smell was so overwhelming for business owners they feared it may

have economic ramifications. “If nothing its done and the smell becomes unbearable, I’m

fearful of what that will really do to the business and the appeal of being in La Jolla,” one

restaurant owner remarked.75 In 2013, the city spent over $50,000 to spray an excrementeating bacteria onto the rocks, but since then the stench has returned in even greater

force.76

Seagulls certainly fit the bill as trash animals. Seagulls and humans certainly have

a symbiotic relationship with gulls resting on the smaller end of that negotiation. Rarely

are they thought of as majestic or cute creatures. More often words like nuisance and pest

are used when referring to the sea birds. They are often the victim of ridicule and vitriol

on Southern California beaches. Gavan Watson reminds us that historically this is due to

their propensity to feed off of landfills and human trash as much as it is their subjectively

Jyllian Kemsley, “Bird Waste CleanUp, National Lab Caught on Camera,” Chemical and

Engineering News, August 5, 2013, http://www.kpbs.org/news/2013/dec/27/san-diego-sued-oversea-lion-bird-poop/.

73

KGTV, “City of San Diego Hires Blue Eagle to Remove Bird Poop from La Jolla Cove, Video.

Online. http://www.10news.com/news/city-of-san-diego-hires-blue-eagle-to-remove-bird-poopfrom-la-jolla-cove-06172013.

74

Trageser, “San Diego,” (above, n. 71)

75

Ian Lovett, “California Cove Blessed with Nature’s Beauty Reels from Its Stench,” The New

York Times, November 24, 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/25/us/california-coveblessed-with-natures-beauty-reels-from-its-stench.html?_r=0.

76

Kemsley, “Bird Waste,”(above, n. 88)

72

22

noisy sound.77 All gull species use their calls to carve out and mark small territories on

rocks.78 So while humans mark their territory with seaside patios and lily-lined gardens,

gulls do so with their seemingly annoying calls.

The cormorant too can be seen as a trash animal. There is a long history of

cormorant hatred among fishermen. They have even been referred to as the “devil bird”

and “gluttons of the sea.”79 Linda Wires explains we have such a hatred of the birds that

North American wildlife agencies have been personally responsible for killing millions of

the birds with “little biological evidence justifying this as a rational course of action.”80

References to the cormorant as a symbol of gluttony and greed extend as far back as

Chaucer and can be read in Jane Eyre.81 The cormorant is the epitome of a trash animal as

it has “emerged as the victim of many flawed processes and unfair judgments.”82

It is controversial to claim La Jolla, a town whose residents have included John

McCain, Mitt Romney, Deepak Chopra, and Gregory Peck, as a trash community in the

purest sense because the people who live there certainly do not think of themselves as

trash nor in most circles are they considered to be redundant or wastrels. Additionally, the

La Jolla cove and much of the surrounding water is protected as an underwater ecological

reserve. So when I refer to La Jolla as a trash community it is in the sense that the wealth

Watson, Gavan. “Cultural Blind Spots and the Disappearance of the Ring-Billed Gull in

Toronto,” in Trash Animals: How We Live with Nature’s Filthy, Feral, Invasive, and Unwanted

Species, eds. Kelsi Nagy and Phillip David Johnson II, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota

Press, 2013) p. 4589. E-book.

78

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology: All About Birds, February 17, 2015,

http://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/herring_gull/sounds.

79

Richard King, The Devil’s Cormorant: A Natural History, (Lebanon, NH: University of New

Hampshire Press, 2013)

80

Wires, Linda. The Double-Breasted Cormorant: Plight of the Feathered Pariah, (Cambridge:

Yale University Press, 2014) p. xv.

81

Susan Taylor, “Brontë’s Jane Eyre,” The Explicator, 59:4 (2002): p. 182.

82

Wires, The Double-Breasted Cormorant, (above, n. 96) p. xv.

77

23

and riches seen in La Jolla are the counter balance to the waste of the L.A. River Basin

and Salton Sea. Both are products Bataille’s theory of consumption. It is merely that one

is exalted while the other abjected. Waste is not just the unwanted, not just the

undesirable, but waste too can be the excessive, the lavish, the splendid. If we think of

waste in this double-jointed manner, La Jolla and the L.A. River Basin become different

sides to the same issue – that of consumption. Waste becomes the carrot to increase only

the perpetual cycle of consumption. La Jolla becomes the pristine sweet smelling garden

of hyper capitalism while the L.A. River and the Salton Sea become the rotten effusion of

consumption. All are part of the same system; we could not have one without the other.

There is no trash without excess; no excess without consumption.

In the animal world, noise and excrement is often seen as a form of appropriation,

as a marker of personal or community territory. Lions piss around their dens. Gulls and

cormorants call to guard their rock. Sea lions similarly bark to ward off unwanted

intruders. Dogs urinate on stop signs. Michel Serres reminds us that historically it was

the same for humans; if you spit in the soup you keep it.83 Excrement and urine of others

has served as a territorial deterrent for humans since ancient times. In this way property

rights can be seen as having animal origins.84 Our desires to “own” a sweet smelling,

piece of land above the La Jolla cove is an example of our desires to rid our territory from

intruders. Modern society has evolved to rid itself of these animal origins and in doing so

has rid itself or made to disappear what Serres calls hard pollution or things like

excrement, garbage dumps, industrial waste and in turn appropriated through the

pollution of what he calls soft pollution or billboards, signs, and I might add extravagant

83

84

Michel Serres, Malfeasance: Appropriation Through Pollution, 2

Ibid., p. 14

24

real estate development and perhaps even meticulously landscaped Southern California

lawns. This type of pollution was the result of the human will to appropriate the world.85

The human appropriation of the world extends to our desire to create a world absent of

foul smells.

La Jolla’s battle with the excrement-covered cove reminds me of the fragrant

utopia described in Aldus Huxley’s Brave New World. If you recall smell and odor is a

symbol for the “artificially designed and enhanced environment of the Utopia.”86 La

Jolla like much of Southern California is a sort of simulacrum of reality. As Michael

Sorkin and others have described, the urban design of Southern California is an attempt

to create a hyperreal space, a utopic landscape that has been wiped clean of its true

history.87 An often-overlooked aspect of this utopic space is the importance of smell in

its creation. Residents plant nice smelling lilacs and herbs and line their houses with

African daisies in contribution to the olfactory utopia. In Brave New World we see what

can happen when this olfactory utopia is disturbed. Huxley describes how one of the

savages, who represents the Other and the antithesis to the utopians, became enamored

with a utopian woman because of her godly smell. He was under the artificial spell of her

smell. It is not until he catches a slight whiff of her musky scent that he is awakened to

the horror of her true immortal identity. In Huxley’s novel “fragrance stands for artificial

and superficial pleasure, while foulness for unpleasant but meaningful reality.”88 Stench

in the confines of the novel awakens us to reality. Stench like that of excrement can

85

Ibid., p. 68.

Classen, Aroma, (above, n. 47) p. 178

87

Michael Sorkin, “See You in Disneyland,” ed. Michael Sorkin, Variations on a Theme Park:

The New American City and the End of Public Space, (New York: Hill and Wang, 1992) pp 205232.

88

Classen, Aroma, (above, n. 47) p. 179.

86

25

shock us from our ideological slumber into an olfactory revelation of awareness. Yet as

the example of the Citizens for Odor Nuisance Abatement has shown us this shock is

brief, and more often then not people want to return to the pleasant aroma of ideology.

When we breathe in foul air, it recirculates within our bodies. And each

inhalation and exhalation “reveals a boundary between the body and that which is not the

body.”89 Our desire to rid our bodies of this smell of death and excrement is seen in the

way our body contract and gags; “it is a powerful response which I am certain is an

adaptation against a potential threat.”90 It is likely an olfactory reminder of our own

impending death, and our fear of it is simply manifested in our negative bodily response.

The citizens of La Jolla are trying to push aside the reminder of their own death as much

as they are trying to force their will upon the natural world. In doing so they are erasing

the connective tissue between themselves and the natural world. It is much easier to

forget, to have waste remain invisible. It is more profitable, and there is less vomiting.

CASE STUDY III: THE SALTON SEA

“The spirit of dead things rises over the earth and over the waters, and its breath

forebodes evil.” – Ivan Klima91

Finally we return to the anecdote, which began this essay. Perhaps symbolic of

the ultimate simulacrum of nature, the Salton Sea is one of the finest examples of a part

human-made, part natural, part death trap, trash community. It is an example of

modernity’s failed project to control and order nature and a place where we can literally

Natasha Seegert, “Dirty Pretty Trash: Confronting Perceptions through the Aesthetics of the

Abject,” The Journal of Ecocriticism, 6:1 (2014): p. 4.

90

Ibid., p. 3.

91

Ivan Lima, Love and Garbage, (New York: Vintage International, 1990) p. 18.

89

26

count the death toll from the polluting effects of our consumptive thirst. It is also a place

where olfactory power has played and continues to play a significant role in its

construction. The Salton Sea was created due to Southern Californian’s thirst for

consumption. The Sea sits at the site of an ancient inland sea named Lake Cahuilla and

on a historical riverbed of the Colorado River. It was thought the endless spaces of

unforgiving desert that claimed this space could be tamed. It was thought that the fertile

soil could be transformed into a land capable of sustaining “tens of thousands of

prosperous people.”92 And so Charles Rockwood and George Chaffey established the

California Development Company, named the region the Imperial Valley, and began

advertising it as a valley of ripe, lush agricultural land to prospective buyers.93

They dug a canal from the existing riverbed of the Colorado River through to the

low-lying space of ancient Lake Cahuilla. The canal provided an agricultural bounty for

the farmers of the Imperial Valley, but that bounty required more water, so more cuts

were made into the Colorado River to feed the canal. Like most attempts to hold back the

forces of nature, Rookwood and Chaffey’s project was doomed to fail. In the winter of

1904-1905 the Colorado River flooded so much that it overtook the new cuts and soon

jumped its banks reclaiming its historic riverbed and flooding the Imperial Valley and

recreating Lake Cahuilla.94 It was not until three years later that the uncontrollable flow

could be harnessed. By that time it had already formed the Salton Sea.95 It was thought

the Sea would soon dry up, but due to agricultural run-off it remained partially filled and

only slowly receded.

92

Lawrence Hogue, All the Wild and Lonely Places: Journeys in a Desert Landscape,

(Washington D.C.: Island Press, 200) p. 133.

93

Ibid., p. 134.

94

Ibid., p 135.

95

Ibid., p 135.

27

Soon the Salton Sea became the jewel of the American Southwest. It became a

recreational mecca, which rivaled that of Yosemite. In the 1950’s the California

Department of Fish and Game took out huge nets into the Gulf of California and threw

them out into the ocean. They transported their entire haul, which included bonefish,

corvina, roosterfish, halibut, totuaba, anchoveta, and many other species and offered them

the vacant sea to colonize.96 Later in the 60’s the DFG planted tilapia into the sea. The

majority of the different species did not survive, but those that did like corvina and tilapia

turned the Salton Sea into a fisherman’s paradise. In a matter of years yacht clubs and

resort villages were built along the “Salton Riviera.” It became so popular, celebrities like

Frank Sinatra and Sonny Bono were known to frequent. There were endless parties. The

newly formed sea had become the place to be in Southern California. The Salton Riviera

was one of the last great California boomtowns. Thousands of plots were designed.

Sewer, water, and electricity were grid. The place was set up to become Lake Tahoe of

the south. But the parties and celebration were short lived. The lofty dreams of real estate

developers and businessmen would quickly meet their demise, and the dreams like the

tilapia would decay into a slow, smelly afterlife in the desert.

The promise of the boomtown died with the rising salinity of the lake. Because

the Salton Sea had no output for the incoming agricultural run-off, its salinity levels rose

each year, eventually retaining a much greater salinity than the ocean. 97 Baking in the

hot desert sun, the water quickly evaporates, and like a pot of boiling ocean water the salt

levels almost constantly increase as the water levels decrease. The massive amounts of

fertilizer that make their way into the sea from agricultural run-off causes massive algae

96

William DeBuys and Joan Myers, Salt Dreams: Land and Water in Low-Down California,

(Albuquerque: University of New Mexico, 1999) p. 231.

97

Ibid., p. 230.

28

blooms and corresponding fish die-offs.98 In the 1970s a number of floods wiped out

some of the development. It was the combination of the floods and the smell of

putrefying fish in the hot desert sun that drove people from the Riviera. The Sea came to

represent death and the dead.99 As Bataille reminds us, “What relates to death may be

uniformly detestable, and may only a pole of repulsion for us, situating all value on the

opposite pole.”100 The Salton Sea soon became a repulsive, detestable landscape – it

became valueless. It became the forgotten wasteland of society. Today with its

crumbling yacht clubs, plywood shacks, motorhome communities, and banks sometimes

covered in the rotting remains of putrefying tilapia, the murky brown waters and sundried

banks of the Salton Sea provide a post-apocalyptic scene, the kind only remade in horror

movies.

When people fled the Salton Sea, when they associate the stark landscape with the

wasteland of infinity, they are trying to escape “if not death, at least the anguish of” it.101

And as Bataille argues the human attempt to escape death is an attempt to remain in the

sovereign world, to remain human. In the West water is perhaps the best example of

humans’ perpetuation of the myth of sovereignty. In the West, water is property. By

diverting water from the Colorado River, Rookwood and Chaffey were claiming it as

theirs. They were converting water into money, into food, into real estate, into capital.

The failure of the Salton Sea was not in the accidental breach of the canals. The failure

was that those that caused the accident did not understand the negative effects

Jeffrey P. Cohn, “Saving the Salton Sea: Researchers Work to Understand Its Problems and

Provide Possible Solutions,” BioScience 50:4 (2000): pp. 295-301.

99

An example of this is the neo-noir crime film The Salton Sea, which stars Val Kilmer. The film

depicts the Salton Sea as an unforgiving, desperate place.

100

Bataille, The Accursed Share. Vol III, (above, n. 40) p. 218.

101

Bataille, The Accursed Share. Vol III, (above, n. 2) p. 218.

98

29

development can have. They did not have foresight. In turn they were creating a system

dependent on excess. Excess, beyond excess sunshine, is not something the harsh

environment of the Anza-Borrego Desert can provide. What remains of the Salton

Riviera is an area with little hope. Few people still eek out an existence on the shores of

the sea. Some hope for a return to what briefly was; others like those in the nearby

squatter community of Slab City find refuge in knowing it is a place where they can

disappear off the grid and be forgotten by the rest of the society.

The Salton Sea ecosystem is a delicate balance of saline, migratory birds, and

fish. The balance of the system begins with phytoplankton, which “harness solar energy

to metabolize organic compounds.”102 Algae feed on the phytoplankton. Bacteria

decompose the defunct algae, and then the pile worm feeds off of the bacteria and algae.

The small bairdiella or silver perch and the tilapia feed off of the pile worm, and then

finally the orangemouth corvina feeds off of the perch and tilapia.103 The sea is also

home to hundreds of species of migratory birds. In fact it is the largest wetland in

Southern California. The health of the sea relies on this delicate balance. Too much

saline or too much algae decreases oxygen levels and the sea becomes eutrophic and the

fish cannot survive. The cultural eutrophication of the sea occurs because of the large

amounts of fertilizer that make their way into the water. It raises selenium, lowers

oxygen, and kills fish. Since 1992 hundreds of thousands of birds have died due to this

cultural eutrophication; the number of tilapia and corvina is uncountable. The Salton Sea

has become accustomed to death and decay. In a typical year thousands of fish die on its

banks to rot and decompose in the desert sun.

102

103

DeBuys, Salt Dreams, (above, n. 97) p. 231.

Ibid., p. 231.

30

In the summer of 2013, a year after the putrefying smell of tilapia carcasses swept

through Southern California like a fetid tsunami of rot, an interesting phenomenon

developed. Not all of the fish from previous fish kills including the one a year before

were washed to the banks. Some sank to the bottom. In the delicate ecosystem of the

Sea, “When fish carcasses from previous kills sank to the Salton Sea sediment-water

interface, anaerobic bacteria attacked fats converting them to free fatty acids, forming

adipocere,” or waxy balls of decomposed flesh otherwise known as corpse wax.104

Adipocere inhibits further decay. It is putrefaction in suspension. The shores lined with

corpse wax are a reminder of the utter purgatory facing the Salton Sea. Like the waxy

balls of partially decomposed flesh on its shores, the Salton Sea remains in a somewhat

suspended state of decay.

The people and fish of the Salton Sea constitute a trash community because both

of them are the forgotten, unwanted remains of consumption. Many people are disgusted

by the tilapia of the Salton Sea.105 The fertilizer pollution and selenium levels of the sea

make their way into the fish, and it is advised not to eat them.106 Residents surrounding

the sea pay no attention to the high selenium levels and eat the fish in abundance. The

tilapia are unwanted, undesirable, and in the state of suspended decay, disgusting. The

residents of the ghost town are societal caste outs. William DeBuys describes the people

who live around the Salton Sea as those who have been “shooed” from place to place, but

Betts, Thomas et al., “The Unusual Occurrence of Adipocere Spheres on the Hypersaline

Lacustrine Shoreline, Salton Sea, California,” Palaios. 29:11 (2014): pp. 553-559.

105

Tilapia are an example of the subjectivity of the definition of trash animals. Tilapia are a

somewhat regrettably valued food source through much of the US. Like carp they are benthic

feeders, but most tilapia farmed in Asian markets are fed human feces. The tilapia of the Salton

Sea are not these same tilapia at least in public perception. It is the abundance by which they rot

on the shores and the putrid stench emanating from their decaying bodies that transforms them

into trash here.

106

Tony Perry, “Salton Sea’s Star has Fallen,” Los Angeles Times, May 21, 2012.

104

31

no one has bothered to shoe them from the Salton Sea.107 No one shoes them from the

Salton Sea because they live outside of the territory of homogenous society. It is only

when the smell of the trash community infiltrates downtown Los Angeles that most are

even aware of its presence. The smell of the Salton Sea awakens us to horrors of our

consumptive practices. It awakens us to what Marcel Proust might call the involuntary

smell of “pure truth.”108

Proust believed that involuntary smells provided a purer memory than voluntary

smells. He and others like Samuel Beckett believed that because we do not call them

forth they reveal “kernels of pure truth.”109 Smelling rotting tilapia on the shores of the

Salton Sea forces us to confront the history of our place within the eco-cultural

community of the Sea and the problems that can arise if human consumption is not in

lockstep with natural ecosystems. Smell in this way is an olfactory kernel of truth.

CONCLUSION

The structuring of social space is designed to make capitalism and ideology

invisible so that we may continue to consume blindly. Smell makes the invisible, visible

and forces us to confront the legacies of consumption. The awakening of our olfactory

lobe to the smell of death, decay, and excrement can insight us to moments of lucidity, to

an awakening of our conditions of being. We can flush away and brush aside the

unwanted trash through sewer systems, but as Zizek reminds us, when that waste appears

in our olfactory lobe it can be a disturbing phenomenon.110 Industrialization brought with

107

DeBuys, Salt Dreams, (above, n. 97) p. 197.

Shepard, Neurogastronomy, (above, n. 8) p. 179.

109

Ibid.

110

The Perverts Guide to Ideology, directed by Sophie Fiennes, (Los Angeles: BFI, 2013).

108

32

it pollution, foul air, toxic water, and the excess of the rich. The pollution of our daily

lives is invisible – as such it is acceptable. As Natasha Seegert argues, “Pollution

becomes a new baseline of banality.”111 Smell can be the most powerful of senses. As

Theodore Adorno and Max Horkheimer remind us “When we see we remain who we are,

when we smell we are absorbed entirely.”112 The smell of rotting fish and cormorant shit

absorbs us entirely within the dark processes of life we wish to forget, those we push

deep into the recesses of our unconscious. The smells absorb us within the Other we

have fought so tragically to hide. This absorption forces us to confront our historical

reality. As we have seen smell can be so powerful, it can incite social change.

Trash communities are the living excess of consumption. Their odor escapes the

coherence of the social order, haunting it, living above it, reminding us of our own

mortality. Bataille might argue the odor produced by trash communities is the sacrificial

effusion or that which ruptures the power to the myth of sovereignty. As a result of this

rupture of smell it also simultaneously produces moments of sovereignty – the choking

and vomiting on the stench of the Real dissolves rationality. Trash communities operate

at both a marginalized and a sovereign level as they produce a putrid stench so powerful

that it can reign power over the homogenous society, which continues to marginalize

them. So when the smell of a trash community is inhaled by the social consumer body, it

has the ability to question the sovereignty of humans. A kernel of truth of our own

impending death and of the reality of our unstable is revealed to us through the putrid

Seegert, “Dirty Pretty Trash: Confronting Perceptions through the Aesthetics of the Abject,”

Journal of Ecocriticism, 6:1 (2014): p. 3.

112

Theodore Adorno and Max Horkheimer, Dialectic of Enlightenment, (Stanford: Stanford

University Press, 2002) p. 151.

111

33

funk and shit of the Real emanating from the rotting fish carcasses and splattering of

seabird excrement on rocky cliffs.

These three sites of trash communities where waste and pollution become banally

absorbed within our unconscious are revealed to us through their smell. The putrid

stench of wastewater in the forgotten L.A. River Basin brings the river’s history into

view. Rotting carp on the shores of “Nigger” Slough, illustrate the power of the

subjectivity of smell. Smell can snap us from our ideological stupor and for a moment

force us to confront our selves and these three sites and their inhabitants as historical

entities. The wafting odor of seagull and cormorant excrement in La Jolla awakens us to

the reality of our own ways of marking boundaries and of the variety of ways in which

consumption creates pollution. It forces us to realize that humans, even (or perhaps

especially) those eating twenty-dollar crème brulee, are connected to the natural world

around us. And the putrid, rotting egg stench of decaying tilapia carcasses smacks us in

the face with the horrors of modernity. In the end the smell of death and excrement

connects us to the very processes of life and reminds us of our own human-animal

existence.

34