Writing a Seminar Paper (PowerPoint)

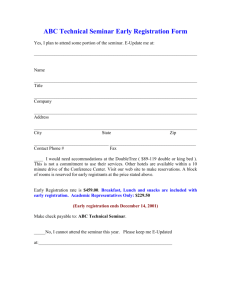

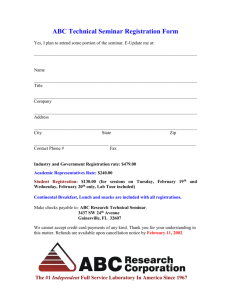

advertisement

Writing a Seminar Paper Approaching the Topic and Claim, or “How to Write an ULWR With a Purpose, Without Writing a Brief” Why Write a Seminar Paper? • Opportunity to publish, develop professional reputation • Writing product for jobs, especially judicial clerkships • Opportunity to specialize in topics of interest, to learn substantive law at a new level • Self-fulfillment achieved from producing an independent product – one of your last experiences in truly independent scholarly writing before you will be asked to be an advocate Writing Contests Legal writing competitions blog: http://legalwritingcompetitions.blogspot.com/ One comprehensive site is http://law.richmond.edu/students/writing/catalog/ Another good website is available at http://law.lclark.edu/academics/student_writing_ competitions/ Books about Seminar Papers • Eugene Volokh, Academic Legal Writing: Law Review Articles, Student Notes, and Seminar Papers (4th ed., Foundation Press 2010) – emphasis on picking topic • Elizabeth Fajans & Mary L. Falk, Scholarly Writing for Law Students: Seminar Papers. Law Review Notes, and Law Review Competition Papers (4th ed., West 2011) – emphasis on the writing process Picking and Grounding a Topic • My jurisprudence final exam: 50% for the answer/50% for the question • Topic and the question asked (thesis) in a seminar paper is important to the research and writing process that will follow What is a Good Topic? • Relates to the substance of the class – e.g., I teach energy law. This is probably not the class for a paper on the equal protection clause. • Has some relevance to legal debates – e.g., a paper on whether the planet will come to an end because of the depletion of fossil fuels or whether it is sustainable is probably better written for an ecology class or an economics class. • Has some legal, analytical or methodological substance – can you envision the paper drawing on legal doctrine, taking an analytical perspective (presenting/addressing arguments that would be appropriate to a law class), or will it have an analytical approach (historical, philosophical, psychological, economic, empirical)? E.g., of Kyoto. • Will be researchable? – e.g., German climate change policies. How Does Topic Relate to Research? Do not pick your topic in a vacuum! 1) Initially, it will be best to treat your topic as tentative, refining the topic along the way. This is your “drop/add” period. – At this stage the topic will narrow your research, but not so much so that it hamstrings you to a very specific question. Researching the Paper Topic 2) Make sure that you have seriously READ at least 5 primary and secondary sources relating to your topic. Researching the Paper Topic 3) Refine your topic and settle in on a more precise specification. “Drop/Add” period is over. The Next Step – Relating the Topic to a Claim A claim = a thesis According to Volokh, “Good legal scholarship should make 1) a claim that is 2) novel, 3) nonobvious, 4) useful, 5) sound and 6) seen by the reader to be nonobvious, useful and sound.” The Claim What are some examples??????? The Claim, examples 1) Law X is unconstitutional because . . . . 2) The legislature ought to enact the following statute . . . . 3) Properly interpreted, this statute/regulation/treaty means . . . . 4) This case/doctrine explains/contradicts this other case/doctrine because . . . The claim, examples 5) This law is likely to have the following side effects . . . . [ and therefore should be rejected or modifed to say . . .] 6) Courts have interpreted the statute/regulation/treaty in the following ways and therefore the statute/regulation/treaty should be amended as follows . . . .because . . . 7) My [empirical, historical, philosophical, economic, psychological, or religious] perspective on this law shows the law is flawed and should be changed [or not]. Approaching the claim with modesty -Develop your claim while you are still researching -At this stage, treat the claim as a hypothesis -Data (i.e., cases, secondary literature, etc.) may lead you to reject or modify the claim, but do not wed yourself to the claim against clear evidence that contradicts it, unless you can reject/distinguish/explain away that evidence in a sound manner Keeping an open mind • Talk to faculty about your claim • Modify it by adding nuance – factors, exceptions, etc. • Leave open the possibility that you may need to substantially modify your claim during your writing process – the other 50% • Distinguish the descriptive from the prescriptive parts of your claim Once you select a topic and identify a claim, the writing process will not take care of itself. However, you will now be writing with a purpose, rather than writing in search of one. THE END