Writing about Literature

advertisement

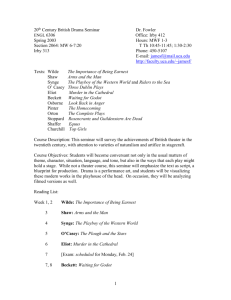

Writing about Literature Introduction to Literature Lecture 12 Critical Thinking intellectually disciplined process actively and skillfully conceptualizing, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and evaluating information gathered from observation, experience, reflection, reasoning, or communication based on intellectual values such as clarity, accuracy, consistency, relevance, depth, fairness Critical Thinking Involves the skills detailed above the intellectual commitment of using those skills to guide behavior fairmindedness to avoid skillful manipulation of ideas to avoid irrationality, prejudices, biases, distortions, uncritically accepted social rules and taboos, self-interest, and vested interest to avoid thinking simplistically about complicated issues to consider appropriately the rights and needs of others Critical Thinking In writing To learn to articulate ideas properly To accumulate data To arrange data into an appropriate argumentative line To learn how to refute mistaken, incorrect, erroneous opinions To learn how to draw a relevant conclusion from premises Style Guides The formal requirements of a research paper Joseph Gibaldi: MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers New York: The Modern Language Association of America (7th edition) Style Guides Good writing Involves Grammar, structure, style Mechanics, punctuation Usage Clarity, coherence, unity in sentence structures in developing paragraphs Exposition, argument, persuasion Conclusion Abstract, summary Planning, writing and presenting a critical paper The purpose is to enable the student to demonstrate that (1) she/he knows how to use libraries and other sources effectively to locate relevant materials (2) she/he can prepare and write up a sustained and logically structured academic argument in clear prose (3) she/he can present her/his work well, using appropriate scholarly conventions Process Deciding on a topic Wide range of possible research topics At BA and MA levels usually assigned to students When the task is assigned, questions to be asked are: What are the key studies in the field? What kinds of approaches have been taken to the subject? Process Turning a topic into an argument To give a direction To develop a set of questions to be answered or problems to be solved in the paper Information and data should be gathered in order to answer the questions, solve the problems A good paper takes the form of an argument Process Some ways of turning a topic into an argument An argument for or against an existing critic or critical position An argument about the importance of a particular influence on a writer or an influence exerted by her/him An argument turning upon the nature of the genre of a work An argument about the significance of a little-known or undervalued author or work An argument about some historical or literaryhistorical aspect of literature Process Working out a structure Consider the question of length of the planned paper Internal division of the argument into introduction, elaboration, conclusion The elaboration section may be divided into smaller units Development of the argument Process Preparing a research proposal When registering for a BA thesis Should contain: Title Argument – should be concise Materials – should be presented more in detail (primary sources, secondary sources) Conclusion – provisional References – key primary and secondary texts Bibliography – all relevant primary and secondary texts Process Writing a paper taking notes – techniques from the first rough draft to the final version format of the text setting out references – acknowledge quotations Critical genres Review, criticism Research paper, scholarly essay, personal essay, brief notes, letter to the editor Book chapter Collection of essays, critical papers, reviews Thesis, dissertation Book, monograph Donald Hall and Sven Birkerts Writing Well Longman 9th ed. Beth S. Neman Teaching Students to Write Oxford University Press 2nd ed. Critical Thinking The Act of Writing Writing with Purpose Some magazines of literary criticism The articles and books reviews are exemplary in their layout, intellectual precision, competence, and fairmindedness Times Literary Supplement founded in 1902 London Review of Books founded in 1979 The New York Review of Books founded in 1963 Periodicals with literary essays • TLS The Times Literary Supplement A.http://entertainment.timesonline.co.uk/tol/a rts_and_entertainment/the_tls/ • London Review of Books http://www.lrb.co.uk/ • The New York Review of Books http://www.nybooks.com/ JACQUES LEMARCHAND IN ‘FIGARO LITTERAIRE’ 17 January 1953, 10 I do not quite know how to begin describing this play by Samuel Beckett, ‘Waiting for Godot’ (directed by Roger Blin, now playing at the Théâtre de Babylone). I have seen this play and seen it again, I have read and reread it: it still has the power to move me. I should like to communicate this feeling, to make it contagious. At the same time I am faced with the difficulty of fulfilling the primary duty of the critic, which, as everyone knows, is to explain and narrate a play to people who have neither seen it nor read it. I have experienced this difficulty several times before; the sensation is infinitely agreeable. One feels it each time JACQUES LEMARCHAND IN ‘FIGARO LITTERAIRE’ 17 January 1953, 10 one is called upon to describe a work that is beautiful, but of an unusual beauty; new, but genuinely new; traditional, but of eminent tradition; clever, but with a cleverness the most clever professors are unable to teach; and finally, intelligent, but with that clear Intelligence that is non-negotiable in the schools. In addition, ‘Waiting for Godot’ is a resolutely comic play, its comedy borrowed from the most direct of all forms of humor, the circus. The Broadway production of Waiting for Godot, which opened April 30 at Studio 54, 2009. The Roundabout Theatre Company's production of Samuel Beckett's allegorical play stars Nathan Lane, Bill Irwin, and John Goodman. Harold Hobson In ‘Sunday Times’ 7 August 1955, 11 Strange as the play is, and curious as are its processes of thought, it has a meaning; and this meaning is untrue. To attempt to put this meaning into a paragraph is like trying to catch Leviathan in a butterfly net, but nevertheless the effort must be made. The upshot of ‘Waiting for Godot’ is that the two tramps are always waiting for the future, their ruinous consolation being that there is always tomorrow; they never realise that today is today. In this, says Mr. Beckett, they are like humanity, which dawdles and drivels away its life, postponing action, eschewing enjoyment, waiting only for some far-off, divine event, the millenium, the Day of Judgment. Harold Hobson In ‘Sunday Times’ 7 August 1955, 11 Mr. Beckett has, of course, got it all wrong. Humanity worries very little over the Day of Judgment. It is far too busy hire-purchasing television sets, popping into three-star restaurants, planting itself vineyards, building helicopters. But he has got it wrong in a Tremendous way. And this is what matters. There is no need at all for a dramatist to philosophise rightly; he can leave that to the philosophers. But it is essential that if he philosophises wrongly, he should do so with swagger. Mr. Beckett has any amount of swagger. A dusty, coarse, irreverent, pessimistic, violent swagger? Possibly. But the genuine thing, the real McCoy. Nathan Lane, left, as Estragon and John Goodman as Pozzo in Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, at Studio 54, 2009 Postlewait, Thomas: “Self-Performing Voices: Mind, Memory, and Time in Beckett's Drama. Twentieth Century Literature, Vol. 24, No. 4 (Winter, 1978), pp. 473-491 Time is the burden in Beckett's drama-both as chronic endurance and as recurrent theme. His characters suffer time without being able to form it and consciousness into a satisfying design. It does not become for them, as it has throughout Western history, a causal principle of existence, the soul and measure of being: the Greek's Alpha and Omega-Chronos (confused with Kronos), Heraclitus' river, Zeno's arrow, Plato's moving image of eternity, Pindar's father of all things, Aristotle's "number of motion in respect of before and after," the Hebraic "Chronicles," the neo Platonist's Nous or Cosmic Mind, St. Augustine's three times (present of things past, memory; present of Postlewait, Thomas: “Self-Performing Voices: Mind, Memory, and Time in Beckett's Drama. Twentieth Century Literature, Vol. 24, No. 4 (Winter, 1978), pp. 473-491 things present, sight; present of things future, expectation) the medieval wheel of fortune, Petrarch's devouring time with the hourglass, the Renaissance's Father Time (half devouring demon, half eternal principle), Spenser's mutability, Shakespeare's Time of many faces (transience, death, decay, tyranny, sweet remembrance, gloomy prospect of "tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow," and historical record of royal and national needs of purpose), Locke's measurable idea of succession and idea of duration, Newton's "absolute, true, and mathematical time," Hegel's dialectical march of the Absolute Idea, Marx's Postlewait, Thomas: “Self-Performing Voices: Mind, Memory, and Time in Beckett's Drama. Twentieth Century Literature, Vol. 24, No. 4 (Winter, 1978), pp. 473-491 progression of economic history, Bergson's duration, Proust's memory, Einstein's relativity, and throughout history the pragmatist's Locks of Opportunity. None of these holds consciousness together for Beckett's characters. Shakespeare writes that time "nursest all and murder'st all that are"; however, it does not even do this in Beckett's drama. It simply runs on and on without cause. Postlewait, Thomas: “Self-Performing Voices: Mind, Memory, and Time in Beckett's Drama. Twentieth Century Literature, Vol. 24, No. 4 (Winter, 1978), pp. 473-491 To illustrate this, Beckett divides Waiting for Godot, Happy Days, and Play into two days or parts that are confusingly the same. And Endgame, while limited to one day and act, is nevertheless the representation of repetitive actions in a daily sequence. […] Life is spent in anticipation of direction and meaning, and when this does not arrive, then life is spent in aimless routine and habit to pass the time of day. The two main "actions" in Beckett's drama are anticipation without much memory (Waiting for Godot) and memory with much anticipation (Endgame). Most of Beckett's short plays dramatize a mind or voice recording in distant isolation the fragmented pieces of Postlewait, Thomas: “Self-Performing Voices: Mind, Memory, and Time in Beckett's Drama. Twentieth Century Literature, Vol. 24, No. 4 (Winter, 1978), pp. 473-491 memory that tumble out of consciousness as words, words, and more disjointed words: Krapp's Last Tape, Embers, Play, Eh Joe, Cascando, Not I, Footfalls, and That Time. Although the action in Waiting for Godot appears to be random, especially from the characters' point of view, the play is organized into a carefully controlled plot. It unifies around two questions that recur throughout the play: "Do you not remember?" and "What are we waiting for?" That is, memory and anticipation. The words "remember" and "waiting" are constantly repeated in the play, closely matched by the words "yesterday„ and "tomorrow." Gordon, Lois: Reading Godot. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2002, p 62 Beckett mirrors the paradoxes of existentialism — the persistent need to act on precariously grounded stages — with the repeated absence of denouement in the enacted scenarios. Since much of act I, with its series of miniplays, is repeated in the second act, which concludes with an implicit return to act I, Beckett creates a never-ending series of incomplete plays within the larger drama, each of which lacks a resolving deus ex machina. The paradox of purposive action and ultimate meaninglessness pervades. A deceptively simple boot routine is rationalized as purposeful activity. Waiting for Godot in New Orleans, 2008 Paul Chan’s production Graver, Lawrence: Samuel Beckett: Waiting for Godot. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004, 20-21 The title, the sense of universal present time, the shape of the plot and of the characters, the often pointed and tantalizing allusions – these obviously invite allegorical interpretation, and for many play goers and readers the invitation has proved irresistible. It is also important to remember that when Waiting for Godot was first performed in the1950s, arguments about systems of meaning were often influenced by a large body of philosophical and fictional writing generally known as existentialist, which seemed at first glance to have marked similarities to Beckett’s work. Although not a cohesive school, the existentialist writers were Graver, Lawrence: Samuel Beckett: Waiting for Godot. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004, 20-21 preoccupied with many of the same vital issues, most notably the problem of discovering belief in the face of radical twentieth-century perceptions of the meaningless or absurdity of human life. A characteristic existentialist response was to accept nothingness, absence, and absurdity as given sand then to explore the way human beings might self consciously form their essence in the course of the lives they choose to lead. The origin of the inclination for transcendence was little agreed upon by such writers as Martin Heidegger, Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus, and Karl aspers; but as Richard Shepard has described it, ‘a radically negative experience is seen to Graver, Lawrence: Samuel Beckett: Waiting for Godot. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004, 20-21 contain the embryo of a positive development – though the psychological and philosophical content of that development is extremely diverse’ (Fowler, p. 82). The pervasiveness of existentialist thinking in the 1940s and 1950s was so great that any work about an individual’s quest for purpose and order in life, especially in relation to an absent or a present divinity, was likely to be discussed in the context of current controversies about existence, essence, personal freedom, responsibility, and commitment. Many philosophers who were not existentialists were also absorbed by these same questions. Graver, Lawrence: Samuel Beckett: Waiting for Godot. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004, 20-21 For instance, Simone Weil, who coincidentally had been a student at l’Ecole normale superieure when Beckett lectured there, published a widely-read book, Attente de Dieu (Waiting for God), just at the time that Beckett and Roger Blin were trying to stage En attendant Godot. Yet there seems to have been no direct connection with or influence of either writer on the other. The issues were in the air. Worton, Michael: “Waiting for Godot and Endgame: Theatre as Text”. In: Pilling, John, ed.: The Cambridge Companion to Beckett. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994, pp 67-87 Beckett's first two published plays constitute a crux, a pivotal moment in the development of modern Western theatre. In refusing both the psychological realism of Chekhov, Ibsen and Strindberg and the pure theatricality of the body advocated by Artaud, they stand as significant transitional works as well as major works in themselves. The central problem they pose is what language can and cannot do. Language is no longer presented as a vehicle for direct communication or as a screen through which one can see darkly the psychic movements of a character. Worton, Michael: “Waiting for Godot and Endgame: Theatre as Text”. In: Pilling, John, ed.: The Cambridge Companion to Beckett. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994, pp 67-87 Rather it is used in all its grammatical, syntactic and – especially - intertextual force to make the reader/ spectator aware of how much we depend on language and of how much we need to be wary of the codifications that language imposes upon us. Explaining why he turned to theatre, Beckett once wrote: 'When I was working on Watt, I felt the need to create for a smaller space, one in which I had some control of where people stood or moved, above all of a certain light. I wrote Waiting for Godot.‘ This desire for control is crucial and determines the shape of Beckett's last theatrical works; the notion that Worton, Michael: “Waiting for Godot and Endgame: Theatre as Text”. In: Pilling, John, ed.: The Cambridge Companion to Beckett. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994, pp 67-87 the space created in - and by - the playscript is smaller than that of the novel, however, needs urgent and Interrogative attention. It is undeniable that, having chosen to write in French in order to avoid the temptation of lyricism, Beckett was working with and against the Anglo-Irish theatrical tradition of ironic and comic realism (notably Synge, Wilde, Shaw, Behan). However, his academic studies had led him to a familiarity with the French Symbolist theories of theatre — all of which contest both French Classical notions of determinism and the possibilities of the theatre as a bourgeois art-form. (68-69) Banville, John: “The Painful Comedy of Samuel Beckett”. New York Review of Books, November 14, 1996 Reviewing among others: Damned to Fame: The Life of Samuel Beckett by James Knowlson. Simon and Schuster Samuel Beckett: The Last Modernist by Anthony Cronin. HarperCollins The World of Samuel Beckett, 1906-1946 by Lois Gordon. Yale University Press Banville, John: “The Painful Comedy of Samuel Beckett”. New York Review of Books, November 14, 1996 However different their approaches, Knowlson, Cronin, and Gordon have a common intention, which is to present in a more appealing light the personality and work of an artist who is too often seen as unapproachably difficult, pessimistic, and misanthropic. At a certain level, all biographies are also autobiographies. Thus Knowlson’s Beckett is not only a great writer but also a kind of super academic, a man steeped in world literature, a paragon of scholarship and learning. Cronin’s Beckett, on the other hand, is a dedicated working artist, not at all as disengaged from the world as he liked to pretend, or as Banville, John: “The Painful Comedy of Samuel Beckett”. New York Review of Books, November 14, 1996 his admirers preferred to believe, an Irishman fond of a drop, a ladies’ man who would sooner essay a song than talk “balls” (a favorite Beckett word) to the likes of Professor Knowlson. In Gordon’s version, Beckett is caught up in and to a large extent shaped by the history of his time, the great events of which are reflected, however obliquely, in his work. All three versions, complementary rather than contradictory, are more or less persuasive, and although few non specialist readers may be prepared to plough their way through all three of these books, taken together they do provide a remarkably rounded picture of a deeply mysterious artist. Summary: Forms News media: scandals, celebrations, promotions Authority issues: censorship, publication rights Format: journals, magazines, collections, monographs online, printed Education: papers, exams, theses, dissertations presentations Audiences: specialised or lay readership Styles: formal, informal from academic writing to blogs The literary essay Flexible form – formal or informal when informal: ideas are presented and argued supported by quotations History of the essay as a literary kind The academic essay Tends to be formal, with a set of rules depending on the area of expertise Essays within various disciplines covered by SEAS: http://seas3.elte.hu/seas/research/publicati ons.html Examples from DES • angolPark http://seas3.elte.hu/angolpark/ • The AnaChronisT http://anachronist.atw.hu/ Style guide for literature: e.g., MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers (Joseph Gibaldi) For a seminar paper • Check requirements of instructor, concerning theme, content, method, form • Select a work or a problem that is of interest to you. • Choose a title that describes a question or problem. • Collect the points that you want to make, and build an argument from them. • Support your points and arguments by quotations from the work(s) in question, using critical sources as well. Always provide the • In the introduction explain what you want to do, such as analyse a book from a certain point of view; compare the treatment of a problem in two or more works; describe a feature of an author's style or other strategy in two or more works by the same author; discuss a more theoretical question of literature using works as examples. Problems to discuss and features to analyse include narration, characterisation, structure, style, motifs, use of symbols, treatment of social or moral issues. • Then go ahead and write an interesting, argumentative paper • In your conclusion summarise your results. What have you learnt from all your work? How could you sum up your most important discoveries for someone new to your topic? Papers at exams • Concentrate on the text • Focus on the question/theme/title specified • Remember helpful ideas from criticism or other works • Try to establish connections between literary texts, between texts and ideas, between texts and criticism • Present an argumentation If you want to test yourself Give a one-line definition of the following terms: • iambic pentameter • narrator • conflict in drama Give a one-paragraph definition of one of the following terms: • narrative voice • elegy Now for a 15-minute task Choose one of the following two extracts and • list possible ways you could analyse the piece • choose one approach and actually carry out the analysis Please find extracts on the next slide. extract No 1 All the world's a stage, And all the men and women merely players. They have their exits and their entrances, And one man in his time plays many parts, His acts being seven ages. At first, the infant, ... • Shakespeare "As You Like It" II.vll. extract No 2 I am the poet of the body and I am the poet of the Soul, The pleasures of heaven are with me and the pains of hell are with me, The first I graft and increase upon myself, the latter I translate into a new tongue. Walt Whitman, “Song of Myself” Section 21 http://www.princeton.edu/~batke/logr/log_026.h tml Now see what you have done • Did you write all 3 one-line definitions? • Did you notice that you only had to write a one-paragraph definition on 1 topic? • Did you notice that you had to list possible analytical approaches to one of the two texts only? • Did you remember to do the list, as well as choose one approach to elaborate?