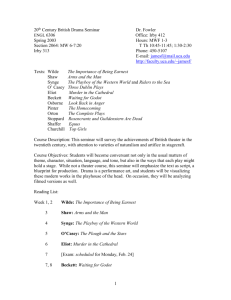

The Times Review of Waiting for Godot

This review of Waiting for Godot appeared in The Times on August 4, 1955. Waiting for Godot is generally

regarded as the masterpiece of the Irish-born poet, novelist, and dramatist, Samuel Beckett, who created some

of the world’s most influential modern experimental literature. The play, which was originally produced in 1952 in

Paris, where Beckett had been a long-time resident, is an austere two-act tragicomedy, in which two tramps,

Vladimir and Estragon, wait for the mysterious Godot to appear. Waiting for Godot addresses the fundamental

human question of the reason and purpose for our existence, and established Beckett’s reputation as a major

exponent of the theatre of the absurd.

Waiting for Godot

Estragon…PETER WOODTHORPE

Vladimir…PAUL DANEMAN

Lucky…TIMOTHY BATESON

Pozzo…PETER BULL

A Boy…MICHAEL WALKER

Produced by PETER HALL

The dramatic instinct reveals itself in a flow of unexpected, absorbing happenings upon the stage.

But a play is something more—it is the flow gradually emerging as some significant image of life.

Mr. Samuel Beckett’s Waiting For Godot, now to be seen at the Arts Theatre in a brilliant

production by Mr. Peter Hall, insists that these truisms shall be restated.

That Mr. Beckett—an Irishman who lives in Paris and writes for preference in French—possesses

the dramatic instinct in a most original sense one cannot doubt. His work in two acts holds the

stage most wittily, but is it a play? Its significance—and how, one feels, Mr. Beckett must abjure

the word—would seem to be that nothing finally is significant.

Two tramps stand near a tree on a derelict country road waiting for Godot. One, played by Mr.

Paul Daneman, manifests a sense of responsibility, a sense of the desperate necessity of their

waiting, that gives him a certain threadbare dignity; the other (Mr. Peter Woodthorpe) is a

whimpering grotesque all for deserting or suicide by hanging. The dialogue between them is a

meandering essay in the inconsequential: if Kafka had tried to write a music hall sketch for two

clowns it might perhaps have struck a similar note. The identity of Godot, the source of his power,

are of course never made explicit though there are some carefully placed remarks about a

saviour.

While the tramps buffoonery and cross-questioning continues what we do feel palpably is a sense

of the passing of time that has been lived. This is interrupted by the outrageous appearance of a

portly, prosperous-looking farming gentleman, who is leading on a rope an ancient servant (Mr.

Timothy Bateson) foaming at the mouth, tethered by his neck, and bent low by the burden of his

master’s suitcase, hamper, and stool. The master, played by Mr. Peter Bull, is not Godot—he is

Pozzo. He represents a bullying authority that occasionally breaks down into floods of childish

tears; but it is an authority none the less and as such it gives the tramps a flicker of hope. They

temporarily forget Godot.

At this point Mr. Beckett would seem to be hinting at some profound interpretation of the relation

between master and servant, but, no doubt deliberately, this is in the event never clarified. A

futile message from Godot, brought in a rather moving little scene by a boy, rounds off the act.

On the next evening everything is repeated with a difference. Pozzo has gone blind and hence is

led by his servant who is dumb. The tramps’ memories begin to fail. The small boy reappears, but

not Godot. The tree has sprouted leaves.

The thoroughbred Irish intelligence of much of Mr. Beckett’s dialogue and his power of theatrical

invention force one to take his fantasy seriously, but it remains a fantasy. His patiently elemental

personages are figments in whom we cannot ultimately believe since they lack universality.

They are, though, remarkably well played in this production. Mr. Daneman and Mr. Woodthorpe

invest the tramps with grandeur. Mr. Bull gives a rich portrait of a weeping blusterer, and Mr.

Bateson as a pathetic mute has one terrifying monologue.

Source: The Times [http://www.the-times.co.uk/]

Microsoft ® Encarta ® Encyclopedia 2003. © 1993-2002 Microsoft Corporation. All rights

reserved.