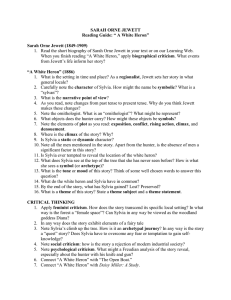

“A White Heron” (1886)

advertisement

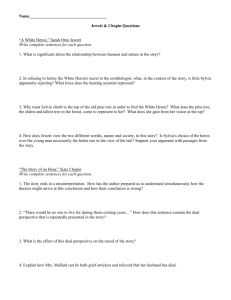

“A White Heron” (1886) Sarah Orne Jewett Sarah Orne Jewett (1849-1909) Born in South Berwick, Maine, daughter of obstetrician Inspired by Harriet Beecher’s Stowe’s Main novel The Pearl of Orr’s Island (1862), she began to write regionalist fiction about coastal Maine Regionalism: branch of American realism representing distinctive characters, dialects, lifestyles and landscapes of various non-urban sections of U.S. Her work was published and encouraged by William Dean Howells, editor of Atlantic Monthly Sarah Orne Jewett (1849-1909) Her most famous work: The Country of the Pointed Firs (1896), a collected of interconnected sketches about coastal Maine From 1881 to her death in 1909, Jewett had close domestic relationship with Annie Adams Fields, widow of editor James T. Fields: they had a “Boston marriage” Relationships between mothers/daughters and among women figure prominently in her fiction. After the Civil War, which killed many men, American women faced new demands and opportunities to form relationships and communities Nature vs. Civilization “A White Heron” sets up a conflict between nature and civilization through the relationship between Sylvia and the young man In this story, nature and civilization are ambiguous categories, mutually interdependent Sylvia Latin sylva=forest Raised 8 yrs in “crowded manufacturing town”: “it seemed as if she never had been alive at all before she came to live at the farm” with her grandmother (¶2) Quiet, “Afraid of folks” (¶3) She knows the land, the birds, the squirrels, etc.; she tames and feeds them (¶16) Young Man A “sportsman”: nature as sport (¶26) An “ornithologist”: kills, stuffs, and preserves birds (¶20): collection & classification Hunting some rare birds for 5 yrs—including white heron, “queer tall white bird with soft feathers and long thin legs” (¶22) Loud: “a boy’s whistle, determined, and somewhat aggressive” (¶5) Gallant, well-mannered (like a knight) White Heron (Snowy Egret) Young Man vs. Sylvia: Issues Speaking: “Speak up and tell me what your name is” (¶7); “The sound of her own unquestioned voice would have terrified her” (¶27) Money: Young man offers $10 for showing him white heron (big money for poor rural folks) Young Man & Sylvia: Issues Violence: “Sylvia would have liked him vastly better without his gun; she could not understand why he killed the very birds he seemed to like so much” (¶26) Love: “Some premonition of that great power stirred and swayed these young creatures” (¶26) Sylvia thinks him “charming and delightful” young man could take home not only the birds but Sylvia too The Pine Tree: Central Symbol Survivor: “the last of its generation. . . . the woodchoppers who had felled its mates were dead and gone long ago ” (¶28). Beacon: “landmark for sea and shore miles and miles away” Prospect: “see the ocean” Mystery: “dark boughs that the wind always stirred” Practical Tool: Locate the white heron Climbing the Tree: Symbolic Journey Struggle associated with birds: “her bare feet and fingers, that pinched and held like bird's claws to the monstrous ladder reaching up” (¶31); “the sharp dry twigs caught and held her and scratched her like angry talons” (¶32) Transition: 1) white oak; 2) pine tree: “dangerous pass from one tree to the other” (¶31): Symbolism? Sylvia has already taken the daring step from town to farm Climbing the Tree: Symbolic Journey World vision: “like the great main-mast of the voyaging earth” (¶33); “truly it was a vast and awesome world” (¶34) Identification: “This determined spark of human spirit. . . . The old pine must have loved his new dependent. . . . the brave, beating heart of the solitary gray-eyed child” (¶33) Discovery of Heron Male heron rises from marsh, perches on pine tree, calls back to mate in nest, in dead hemlock tree Disturbed by cat-birds, the heron returns to his nest “She knows his secret now” (¶36) Sylvia descends Climax: To speak or not to speak? the splendid moment has come to speak of the dead hemlock-tree by the green marsh” (¶38) “No, she must keep silence! . . . Sylvia cannot speak; she cannot tell the heron’s secret and give its life away” (¶40) Sylvia’s Choice (¶40-41) Silence, rather than speaking Poverty, rather than money Loneliness, rather than love Loyalty to nature rather than to a man Peace, rather than violence Nature, rather than the “great world” (¶40) Is Sylvia’s choice natural? Consider that Nature is Loud: “shouting cat-birds” (¶36) Sexual: heron has mate, plumes feathers (¶35); in contrast, Mrs. Tilley’s house is “like a hermitage” (¶14) Violent: cat “fat with young robins” (¶3) Cosmopolitan: the tree connects Sylvia to the “great world” Conclusion Sylvia is not really a child of nature, but cosmopolitan—a child of the town Her loyalty to nature is a sophisticated choice, not an innocent one—comes through experience and suffering Paradoxically, her loyalty and devotion to nature are cultural rather than natural Conclusion Sylvia’s devotion to nature parallels, on a different level, the young man’s devotion to nature—transplanting cultural loyalties (to marriage, science, etc.) back to nature “A White Heron” illustrates the idea of 19thcentury American essayist and poet Ralph Waldo Emerson that nature and humanity complement or complete one another