Corpus Linguistics

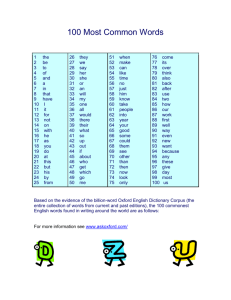

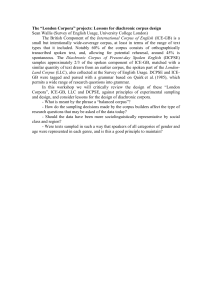

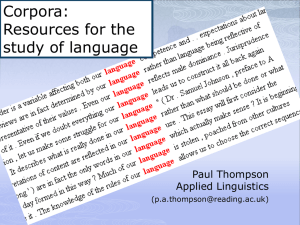

advertisement

Corpus Linguistics Lecture 1 Albert Gatt Contact details My email: albert.gatt@um.edu.mt Drop me a line with queries etc, and to arrange meetings. Course web page Course web page: http://staff.um.edu.mt/albert.gatt/home/teachin g/corpusLing.html Details of tutorials, lectures etc will always be on the web page. Readings for the lecture Downloadable lecture notes (available after the lecture) Suggested text T. McEnery and A. Wilson. (2001). Corpus Linguistics. Edinburgh University Press NB: Over the course of these lectures, other readings will also be proposed and made available, usually online. Lectures and assessment Structure of lectures: all lectures will take place in the lab usually, about half the lecture (1hr) will be devoted to practical work Course assessment: assignment Final essay (ca. 1500-2000 words) Essay topics will involve research on corpora! Questions… ? What is corpus linguistics? A new theory of language? No. In principle, any theory of language is compatible with corpus-based research. A separate branch of linguistics (in addition to syntax, semantics…)? No. Most aspects of language can be studied using a corpus (in principle). A methodology to study language in all its aspects? Yes! The most important principle is that aspects of language are studied empirically by analysing natural data using a corpus. A corpus is an electronic, machine-readable collection of texts that represent “real life” language use. Goals of this lecture To define the terms: corpus linguistics corpus To give an overview of the history of corpus linguistics To contrast the corpus-based approach to other methodologies used in the study of language An initial example Suppose you’re a linguist interested in the syntax of verb phrases. Some verbs are transitive, some intransitive I ate the meat pie (transitive) I swam (intransitive) What about: quiver quake Most traditional grammars characterise these as intransitive Are these really intransitive? One possible methodology… The standard method relies on the linguist’s intuition: I never use quiver/quake with a direct object. I am a native speaker of this language. All native speakers have a common mental grammar or competence (Chomsky). Therefore, my mental grammar is the same as everyone else’s. Therefore, my intuition accurately reflects English speakers’ competence. Therefore, quiver/quake are intransitive. NB: The above is a gross simplification! E.g. linguists often rely on judgements elicited from other native speakers. Another possible methodology… This one relies on data: I may never use quiver/quake with a direct object, but… …other people might Therefore, I’ll get my hands on a large sample of written and/or spoken English and check. Quiver/quake: the corpus linguist’s answer A study by Atkins and Levin (1995) found that quiver and quake do occur in transitive constructions: the insect quivered its wings it quaked his bowels (with fear) Used a corpus of 50 million words to find examples of the verbs. With sufficient data, you can find examples that your own intuition won’t give you… Example II: lexical semantics Quasi-synonymous lexical items exhibit subtle differences in context. strong powerful A fine-grained theory of lexical semantics would benefit from data about these contextual cues to meaning. Example II continued Some differences between strong and powerful (source: British National Corpus): strong powerful wind, feeling, accent, flavour tool, weapon, punch, engine The differences are subtle, but examining their collocates helps. Some preliminary definitions The second approach is typical of the corpus-based methodology: Corpus: A large, machine-readable collection of texts. Often, in addition to the texts themselves, a corpus is annotated with relevant linguistic information. Corpus-based methodology: An approach to Natural Language analysis that relies on generalisations made from data. Example (British National Corpus) British National Corpus (BNC): 100 million words of English 90% written, 10% spoken Designed to be representative and balanced. Texts from different genres (literature, news, academic writing…) Annotated: Every single word is accompanied by part-of-speech information. Example (continued) A sentence in the BNC: Explosives found on Hampstead Heath. <s> <w NN2>Explosives <w VVD>found <w PRP>on <w NP0>Hampstead <w NP0>Heath <PUN>. Example (continued) new sentence <s> plural noun <w NN2>Explosives past tense verb <w VVD>found preposition <w PRP>on proper noun <w NP0>Hampstead proper noun <w NP0>Heath punctuation <PUN>. Explosives found on Hampstead Heath Important to note This is not “raw” text. Annotation means we can search for particular patterns. E.g. for the quiver/quake study: “find all occurrences of quiver which are verbs, followed by a determiner and a noun” The collection is very large Only in very large collections are we likely to find rare occurrences. Corpus search is done by computer. You can’t trawl through 100 million words manually! The practical objections… But we’re linguists not computer scientists! Do I have to write programs? No, there are literally dozens of available tools to search in a corpus. Are all corpora good for all purposes? No. Some are “general-purpose”, like the BNC. Others are designed to address specific issues. The theoretical objections… What guarantee do we have that the texts in our corpus are “good data”, quality texts, written by people we can trust? How do I know that what I find isn’t just a small, exceptional case. E.g. quiver in a transitive construction could be really a one-off! Just because there are a few examples of something, doesn’t mean that all native speakers use a certain construction! Do we throw intuition out of the window? Part 2 A brief history of corpus linguistics Language and the cognitive revolution Before the 1950’s, the linguist’s task was: to collect data about a language; to make generalisations from the data (e.g. “In Maltese, the verb always agrees in number and gender with the subject NP”) The basic idea: language is “out there”, the sum total of things people say and write. After the 1950’s: the so-called “cognitive revolution” language treated as a mental phenomenon no longer about collecting data, but explaining what mental capabilities speakers have The 19th & early 20th Century Many early studies relied on corpora. Language acquisition research was based on collections of child data. Anthropologists collected samples of unknown languages. Comparative linguists used large samples from different languages. A lot of work done on frequencies: frequency of words… frequency of grammatical patterns… frequency of different spellings… All of this was interrupted around 1955. Chomsky and the cognitive turn Chomsky (1957) was primarily responsible for the new, cognitive view of language. He distinguished (1965): Descriptive adequacy: describing language, making generalisations such as “X occurs more often than Y” Explanatory adequacy: explaining why some things are found in a language, but not others, by appealing to speakers’ competence, their mental grammar He made several criticisms of corpus-based approaches. Criticisms of corpora (I) Competence vs. performance: To explain language, we need to focus on competence of an idealised speaker-hearer. Competence = internalised, tacit knowledge of language Performance – the language we speak/write – is not a good mirror of our knowledge it depends on situations it can be degraded it can be influenced by other cognitive factors beyond linguistic knowledge Criticisms of corpora (II) Early work using corpora assumed that: the number of sentences of a language is finite (so we can get to know everything about language if the sample is large enough) But actually, it is impossible to count the number of sentences in a language. Syntactic rules make the possibilities literally infinite: the man in the house (NP -> NP + PP) the man in the house on the beach (PP -> PREP + NP) the man in the house on the beach by the lake … So what use is a corpus? We’re never going to have an infinite corpus. Criticisms of corpora (III) A corpus is always skewed, i.e. biased in favour of certain things. Certain obvious things are simply never said. E.g. We probably won’t find a dog is a dog in our corpus. A corpus is always partial: We will only find things in a corpus if they are frequent enough. A corpus is necessarily only a sample. Rare things are likely to be omitted from a sample. Criticisms of corpora (IV) Why use a corpus if we already know things by introspection? How can a corpus tell us what is ungrammatical? Corpora won’t contain “disallowed” structures, because these are by definition not part of the language. So a corpus contains exclusively positive evidence: you only get the “allowed” things But if X is not in the corpus, this doesn’t mean it’s not allowed. It might just be rare, and your corpus isn’t big enough. (Skewness) Refutations Corpora can be better than introspectvie evidence because: They are public; other people can verify and replicate your results (the essence of scientific method). Some kinds of data are simply not available to introspection. E.g. people aren’t good at estimating the frequency of words or structures. Skewness can itself be informative: If X occurs more frequently than Y in a corpus, that in itself is an interesting fact. Refutations (II) By the way, nobody’s saying “throw introspection out the window”… There is no reason not to combine the corpusbased and the introspection-based method. Many other objections can be overcome by using large enough corpora. Pre-1950, most corpus work was done manually, so it was error prone. Machine-readable corpora means we have a great new tool to analyse language very efficiently! Corpora in the late 20th Century Corpus linguistics enjoyed a revival with the advent of the digital personal computer. Kucera and Francis: the Brown Corpus, one of the first Svartvik: the London-Lund Corpus, which built on Brown These were rapidly followed by others… Today, corpora are firmly back on the linguistic landscape. Summary Introduced the notion of corpus and corpus-based research Gave a quick overview of the history of this methodology Looked at some possible objections to corpus-based methods, and some possible counter-arguments Next lecture We look more closely at some important properties of a corpus: Machine-readability Balance Representativeness …