History of Linguistics Lecture 5

advertisement

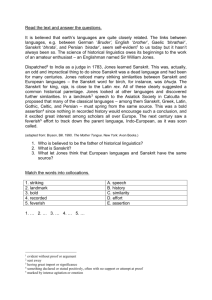

History of Linguistics Lecture 5 Historical Linguistics The Comparative Method and Internal Reconstruction Historical Linguistics Origins of historical linguistics (Renaissance, 17th/18th century) • normative grammar: what is good Dutch, English, etc.? (answer: the oldest stages of the language, before ‘corruption’ took place) • religion: what was the language of Paradise? What happened during and after the Babylonian confusion of tongues? Normative grammar • Balthasar Huydecoper Proeve van Taal- en Dichtkunde, in vrymoedige aanmerkingen op Vondels vertaalde herscheppingen van Ovidius Visscher & Tirion, Amsterdam, 1730 From the preface: Om het goede van het kwaade te onderscheiden, en op eene overtuigende wijze voor te stellen, zijn de Voorbeelden der Ouden ten alleruitersten noodzaakelijk. “To distinguish the good from the bad, and to present this distinction in a convincing manner, the examples from ancient texts are of the utmost importance” Goal of historical linguistics of the Huydecoper variety • enrichment and purification of the native tongue • by looking at older stages, modern loan words and modern variants can be rejected • by looking for old, discarded words, alternatives to newfangled barbarisms can be found Note • During the early modern period, all the main languages of Europe underwent a phase of standardization and purification, because Latin was abandoned, gradually, as the lingua franca of administration and science • Standardization requires some reflection on what variants should be normative • Historical arguments are more neutral, hence persuasive, than sociopolitical ones Example (from Huydecoper) • Vondel: te inf en inf : te dansen en springen • Huydecoper: te should be repeated: te dansen en te springen • So who is right? H.: Me, look at all the ancient examples of coordinated infinitives [In Hoeksema 1995, I show that the Vondel/ Huydecoper disagreement is still reflected in modern Dutch judgments] Religious background Language of paradise/the original language: • • • • Hebrew? Dutch? Unknown? How do we find out? Still an open question today • was there an original single language ? (monogenesis) • or did language come about independently in a number of places? and related to this... • are similarities among the languages of the world evidence of a single ultimate source, • due to genetic factors (innate language system) • or due to certain preferences naturally arising independently? Lambert ten Kate 1674-1731 • Gemeenschap tussen de Gottische spraeke en de Nederduytsche (1710) • Aenleiding tot de kennisse van het verhevene deel der Nederduitsche sprake (1723) • (fairly) worked-out account of the historical relationships between the Germanic languages, including Gothic, Icelandic, Old High German, Old English, etc. • extensive study of the system of strong verbs (uniquely Germanic, among Indoeuropean) • Ten Kate was one of the instigators of the comparative method • influenced the work of Jakob Grimm (19th century) • important also for the history of Dutch phonology, as he gave detailed comments on pronunciation in various dialects of Dutch Sir William Jones THE THIRD ANNIVERSARY DISCOURSE, ON THE HINDUS Delivered 2 February, 1786 The Sanskrit language, whatever be its antiquity, is of a wonderful structure; more perfect than the Greek, more copious than the Latin, and more exquisitely refined than either, yet bearing to both of them a stronger affinity, both in the roots of verbs and in the forms of grammar, than could possibly have been produced by accident; so strong indeed, that no philologer could examine them all three, without believing them to have sprung from some common source, which, perhaps, no longer exists: there is a similar reason, though not quite so forcible, for supposing that both the Gothic and the Celtic, though blended with a very different idiom, had the same origin with the Sanskrit; and the old Persian might be added to the same family, if this were the place for discussing any question concerning the antiquities of Persia. Johann Christoff Adelung (1732-1806) Mithridates, oder allgemeine Sprachenkunde, mit dem Vater Unser als Sprachprobe in bey nahe fünfhundert Sprachen und Mundarte, fortgesetzt von J.S. Vater, Berlin 1806-1817. Early investigation of the connections between European languages and Sanskrit Early overview of the languages of the world from a general point of view Sound Laws • A Reader in Nineteenth Century Historical Indo-European Linguistics • Edited & Translated by W. P. Lehmann • Now available on the World Wide Web: • http://www.utexas.edu/cola/depts/lrc/iedocctr/ie-docs/lehmann/reader/reader.html Rasmus Rask Undersøgelse om det gamle Nordiske eller Islandske Sprogs Oprindelse" (Copenhagen, 1818) “An investigation concerning the source of the old Northern or Icelandic language” Rask: statement of sound laws When in such words one finds agreements between two languages, and that to such an extent that one can draw up rules for the transition of letters from one to the other, then there is an original relationship between these languages; especially when the similarities in the inflection of languages and its formal organization correspond; e.g. Jakob Grimm • Jakob und Wilhelm Grimm: Kinder- und Hausmärchen (18121815) • Jakob Grimm, Deutsches Wörterbuch (1854-1960) • Jakob Grimm, Deutsche Grammatik (1819-1837) Grimm’s Laws Yet more astounding than the accord of the liquids and the spirants is the variation of the lip, tongue and throat sounds, not only from the Gothic, but also the Old High German arrangement. For just as Old High German has sunk one step down from the Gothic in all three grades, Gothic itself had already deviated by one step from the Latin (Greek, Sanskrit). Gothic is related to Latin exactly as is Old High German to Gothic. The entire twofold sound shift, which has momentous consequences for the history of language and the rigor of etymology, can be so expressed in a table: GK Goth OHG P. B. F. P. B.(V) F. F. B. P. | | | T. TH. D. D. T. Z. TH. D. T. | | | K. -. G. G. K. CH. CH. G. K. Examples Latin English piscis fish tenuis thin centum hund(red) pater father tres three octo eight quod (kw) what (hw) No change After /s/: • stare • spuo • piscis - stand/staan/stehen spew/spuwen fisk Karl Verner "Eine Ausnahme der ersten Lautverschiebung," Zeitschrift für vergleichende Sprachforschung auf dem Gebiete der Indogermanischen Sprachen, 23.2 (1875), 97-130 Verner’s Problem • Grimm’s Law had certain ill-understood exceptions, making it more a tendency, than a regular correspondence rule • e.g. brôþar in Germanic corresponds with frater in Latin, bhrotar in Sanskrit • môdar in Germanic corresponds with mater in Latin, matar in Sanskrit so... the interdental (th) in mother is not original Germanic, but a later invention of the English Cf. Old Saxon: Thar ina thiu modar fand (Hel. 818) ‘there the mother found him’ • So what explains the difference between mother (d) and brother (th)? “The only person who has sought an answer to this question, as far as I know, is Scherer in the passage just cited. He assumes that the shift to voiced stops occurs "in frequently used words (like fadar, môdar)" consequently the regular shift occurs in less frequently used words (139). I believe that the venerable author did not wish to attach great weight to this attempt at explanation and that he permitted himself to mention it only as a conceivable possibility. A careful scrrutiny of the Germanic vocabulary is not favorable to his thesis. Is it probable that fadar and môdar were used more frequently than broþar? In Ulfila's writings moreover môdar does not even appear, the word aiþei always being used instead; and he uses fadar only once, otherwise however atta, while his broþar has no parallel synonym at all.” Verner’s solution The original indo-european accent, as it is preserved in Sanskrit (and sometimes ancient Greek), but not in Germanic, where it was lost some time after the application of Grimm’s Law Sanskrit: bhrátar, vs matár, pitár “When the accent in Sanskrit rests on the root syllable, we have the voiceless fricative for the root final in Germanic; on the other hand, when the accent in Sanskrit falls on the ending, the Germanic forms show a voiced stop for the root final.” modern formulation the apparently unexpected voicing of voiceless fricatives occurred if they were non-initial and immediately preceded by a syllable that carried no stress in PIE bonus: not only the voiceless fricatives resulting from Grimms Law are involved in Verner’s Law, but also the voiceless fricative /s/; this /s/ becomes /z/, and by rotacism may later turn into /r/ Compare Middle Dutch vriesen kiesen wesen vroos koos was vroren koren waren gevroren gekoren gewezen internal reconstruction • instead of comparing forms in across languages (comparative method), one may also compare related forms of a word within a language • this is called internal reconstruction • Verner’s Law was a big impetus for internal reconstruction as a source of evidence example • Rijen/rijden/gerejen/gereden • Vrijen/*vrijden/gevreeën/*gevreden Based on this evidence, we may assume that the /d/ is original in rijden and got weakened to a glide, rather than vice versa Junggrammatiker • school of linguists, originating in Leipzig in the 1870’s • influenced by Verner, they proposed that sound changes should be exceptionless • and that laws such as Grimm’s law are not generalizations about data, but comparable to e.g. Newtons laws of gravitation: general truths, not statistical tendencies Some prominent Junggrammatiker • • • • • • • Berthold Delbrück August Leskien Hermann Paul Hermann Osthoff Karl Brugmann Eduard Sievers Wilhelm Braune Hermann Paul Tenets • sound changes are exceptionless • unless they involve analogical change (i.e.: change in a word, not change in a sound) • exceptions may seem to occur because of loan words, or dialect mixture analogical change freeze vriesen vriezen frieren froze vroos vroor fror froze vroren vroren froren frozen gevroren gevroren gefroren • more in general: morphology may bring about changes in words that are not regular sound changes, but allomorphic in nature • example: Umlaut in German used to be phonological in nature, but now it is morphological • Example: Vati, Mutti, Fundi (not: Väti, etc.) loans Dutch German tijd Zeit te zu tuin Zaun tijger Tiger typisch tante typisch Tante dialect mixture gluren loeren meesmuilen smoel lui lieden Family tree vs Wave model • Indo-european branches out in the form of a family tree • This is a model of separation, loss of contact • For contact-induced changes, a wave model is proposed • Wave model important in dialectology (expansion theories)